Young Americans Are Driving Dramatically Less -- Will It Continue?

Americans under 40 are driving dramatically less, according to data from the National Household Travel Survey. The question is: Is car culture in America waning generationally or is this a temporary phenomenon linked to the recession?

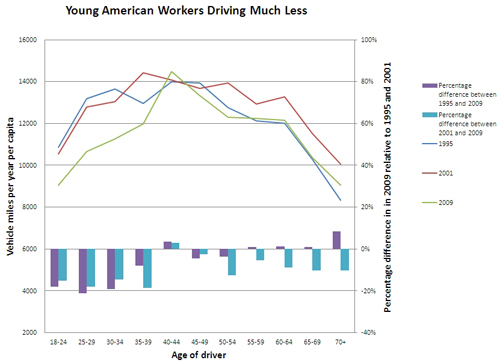

The recession hit younger workers particularly hard. Driving by unemployed Americans between the ages of 18-40 plummeted by 19-24% per person in 2009, compared with 2001. Employed drivers age 18-40 drove between 15-19% less per person in 2009 compared with 2001.

Polls show that younger Americans are more willing to cut back on driving for environmental reasons. Occupy Wall Street and young environmental activists have been a vocal element of movements to block energy infrastructure such as the Keystone XL pipeline. And, young people are apparently less apt to be patrons of NASCAR, which commentators speculate is related to a decline in interests in automobile culture in general.

Thus, if younger Americans are simply going to drive less forever, it would be a very significant paradigm shift for American oil consumption. Americans under 40 accounted for more than one-third of miles driven in the U.S. in 2009.

Some research supports that idea that declining driving patterns by generation Y might be here to stay. Combined with better car mileage standards, that could be good news for US energy security. One explanation for the decline in driving is that cell phones and the Internet allow younger Americans to stay connected with each other without the need to meet in person. The research indicates that it is most true for those under 30 or 35 (the “Gen Y” or “Millennial” generation), but also applies to a lesser degree to generation Xers. In its most recent 2011 survey, Zipcar found 68% of licensed drivers under 35 sometimes choose to spend time with friends online instead of driving to see them, as well as a very substantial 55% of those ages 35-44. As smart phones and programs like Skype become more user-friendly and common, even more are likely to forgo driving.

Social media is also diminishing interest in cars. Mike Cooperman of J.D. Power and Associates’ web intelligence division found that young adults care more about their cell phones than their cars, and the research firm Gartner found 46% of drivers aged 18-24 would choose Internet access over owning a car. Young adults can feel independent with this connectivity rather than needing a vehicle, and such attitudes are likely to continue, even if GM tries desperately use MTV and internet video sensations like Sergio the “Sexy Sax Man” to entice young buyers into showrooms.

Additional clues suggest that this decline in driving among younger Americans may be permanent or continue. As the graph above shows, driving tends to rise until middle age and then fall (so those over 40 are “over the hill” in more ways than one). Yet this may no longer be true for a given age group. The average worker aged 35-39 in 2009 drove less than the similar cohort of workers aged 25-29 in 2001. If driving can both start at a lower level in young adulthood and remain consistent, overall miles driven will drop sharply over time.

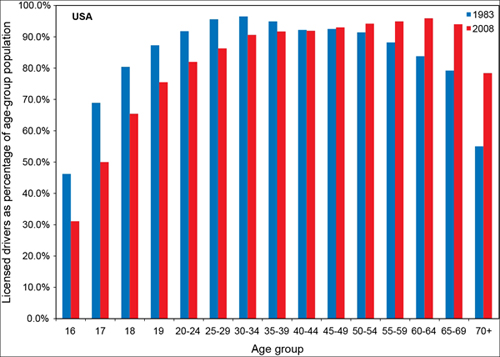

Also, as seen in the graph below from Michael Sivak and Brandon Schoettle of the University of Michigan, Americans under 40 were less likely to have a drivers’ license in 2008 than in 1983. Obviously, one way to reduce driving is to not drive at all, and not having a license is becoming increasingly popular among the youngest Americans eligible to drive.

Another factor leading to less driving, the desire among young adults to live in dense, urban neighborhoods, is also likely to continue. The question is what if gasoline prices were to drop sharply? In this case, would cheap housing in the suburbs and exurbs could seem more desirable again to generation Y? Perhaps not so…a study from RCLCO Consumer Research finds that 77% of Generation Y plans to live in an urban area, and more than half would trade the size of their homes for proximity to shopping or work. Although in slightly lower numbers, many “Gen Xers” who are in their 30s and 40s also want to live in urban areas that are close to destinations they frequent. A rule of thumb is that doubling the density of a neighborhood will reduce miles driven by 20%, though much of the reduction is a result of dense neighborhoods being more likely to have public transportation as well as nearby shops, entertainment and employment.

Some of the reasons cities seem so attractive to younger Americans are not related to oil prices and include falling crime rates, greater acceptance of ethnic diversity, perceptions that cities are more dynamic and exciting, and aversion to long commutes battling traffic congestion. But the thesis hasn’t been fully tested yet. If gasoline prices fall precipitously again some day and the recession were to pass, habits of the baby boom generation might resurface. In that case, even with the overwhelming public opposition that would like remain, policy makers might consider the benefits of a higher gasoline tax to hold the environmental and national security gains that are currently in place.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.