The missing link to a $7 billion market

It’s the biggest renewable energy source you’ve never heard of, and it’s just getting started.

It’s the biggest renewable energy source you’ve never heard of, and it’s just getting started.It has a guaranteed market, with Western European demand expected to triple by 2020. Its global market has tripled over the past decade.

What is it?

Wood pellets.

That’s right, wood pellets. Compressed sawdust.

The demand is primarily coming from Europe, where carbon-reduction targets are driving power utilities — particularly coal-fired power plants — to mix more wood pellets into their fuel supply. Under current targets, many European countries will need to generate 35 percent or more of their electrical power from renewable sources by 2020. And biomass, particularly wood pellets from the U.S., is critically needed to meet those targets.

But this massive export opportunity for the U.S. is being held up for a lack of infrastructure, policy incentives, and financing.

Burgeoning demand

At Infocast’s Biomass Trade and Transport Summit in Charlotte, North Carolina last week, I got an earful about the huge shortfall developing between supply and demand for this crucial, if unsexy, source of renewable energy.

Sean Ebnet is the director of biomass origination for the UK utility Drax Power, whose 4,000-megawatt coal-fired power plant generates about 7 percent of the UK’s electricity. He said that of the country’s 85 gigawatts (that’s 85,000 megawatts) of power generation capacity, one-third is scheduled to be shut down by 2016, including 24 gigawatts of coal capacity (because it can’t meet emissions standards) and 5 gigawatts of nuclear capacity (because it’s reached the end of its life).

Drax’s state-of-the-art plant runs at nearly 40 percent efficiency, and currently gets about 12.5 percent of its fuel — 1.2 million tonnes (Mt) per year — from wood pellets. But Ebnet says they’re just getting started. With new capital investment, the plant will get 20 percent of its fuel from pellets later this year, and ultimately rely on biomass for the majority of its fuel.

According to Jonathan Rager of Georgia-based Poyry Management Consulting, a 50 Mt gap will open between global supply and demand for pellets by 2020. Western European demand will triple, from 11 Mt per year in 2010 to 35 Mt per year by 2020. For perspective, North American wood pellet production capacity was just 4.2 Mt in 2008 according to the U.S. Forest Service. North American pellet exports were just over 2 Mt in 2011, of which over half came from the South.

The demand is certainly there. What’s missing is the supply.

Stranded supply in North America

North America has plenty of supply and could meet that demand, if the pellets could get to market at an acceptable price. According to Rager, there was 106 Mt of unmobilized wood surplus worldwide in 2010, and North America is the best source of new supply, thanks to its healthy and growing forests, good infrastructure, efficient domestic logistics and supply chains, attractive pricing, access to ports & distribution, liquid and open markets, and credible sustainability compliance, which is essential to qualify for use as renewable fuel in Europe.

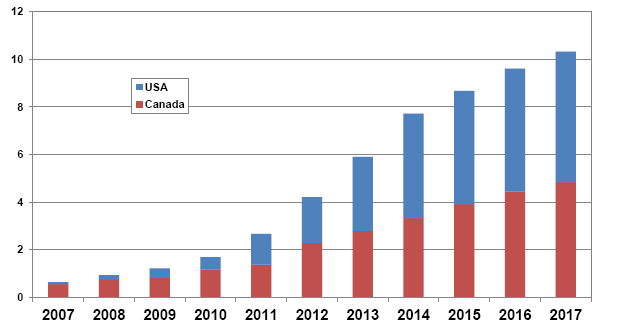

Forecast of wood pellet exports from North America 2007-2017, in million tonnes. Source: Seth Walker, Associate Bioenergy Economist, RISI

A large part of that supply could come from the Southeast, which sports 63 million hectares of timberland and currently holds the “pole position” as a global supplier of wood fibers, according to Rager. The U.S. as a whole has about 204 million hectares of timberland (forests that are available for periodic harvesting).

Unfortunately, as Dean McCraw of Georgia-based McCraw Energy noted ruefully, much of it has been grown for the sawtimber market: dimensional lumber for building materials. When those trees were planted in the 1980s, their landowners didn’t anticipate that the construction industry would crash in 2008. Now it has no place to go, and most of its owners are waiting for the market to recover, or ditching it into the pulp and paper market. Accordingly, McCraw believes we’re headed for a pine pulpwood shortage. New plantings have declined by 50 percent or more in some areas, and aging mom-and-pop landowners aren’t regenerating their land. They’re just walking away from it, or letting it be sold on estate settlements.

The cost of feedstock in the field is low across the board, and for low-grade residue feedstocks like leaves, small limbs and needles, it can even be negative.

While bad news for the landowners (including many Timberland Investment Management Organizations and Real Estate Investment Trusts, which own about 7 percent of US timberland), this is all good news for feedstock supply.

North America also boasts a substantial capacity for pellet manufacturing, which is expected to grow to 10 Mt in 2017, according to Seth Walker, an economist with global biomass information provider RISI.

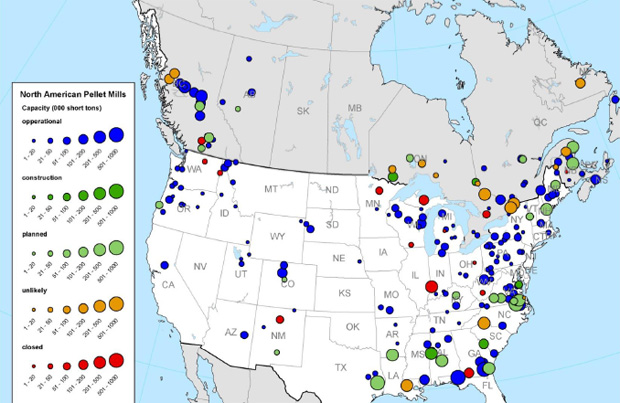

Pellet mills in North America. Source: Seth Walker, Associate Bioenergy Economist, RISI

However, it’s still woefully undersized to meet European demand. Filling the gap will require billions of dollars of investment in new pellet mills, and massive new investment in transportation and logistics infrastructure to get the pellets to market.

The missing link: transportation and logistics

Transportation and loading can be as much as 40 percent of the total delivered pellet cost, according to Brent Mahana of Cooper/Consolidated, the largest independent barge operator in the U.S. Of that cost, roughly 30 percent is fuel. Shipping by barge is by far the cheapest method, followed by rail. But much of the North American supply is too far from an inland waterway or rail loading yard to make it economical. With diesel at $4 a gallon, just 50 miles’ worth of trucking costs to get feedstock to mills and finished pellets to oceanic ports can make or break an entire supply chain.

While some areas of the U.S. have excess capacity in freight rail and rail-to-port infrastructure, like Maine (which sports the lowest shipping cost to Europe at $28 a ton), much of it is either too far from the feedstock supply, or lacks sufficient pellet mill capacity. A great deal of the feedstock is stranded for lack of transportation and logistics capacity.

Geoffrey Clark, executive director of the Rail Authority of East Mississippi, and Sean Dunlap, director of Mississippi’s Wayne County Economic Development district, presented a microcosmic view of the problem. Mississippi has two counties that are 50 to 70 percent covered in forest, but they can’t get the timber out economically without rail. They are trying to get 56 miles of rail built that would restore rail service from Chicago to the Gulf of Mexico and open up eastern Mississippi and western Alabama to pellet transport.

Without more direct rail access, feedstock suppliers in the region have to take very circuitous routes running far to the east or west before they can get south to the Gulf, making the economics unworkable. “That 56 miles might as well be 5000 miles to them,” said Dunlap, calling it “the missing link in the economic spine of east Mississippi.” An estimated 15,000 to 30,000 rail cars a year could transit the line when finished, creating thousands of permanent jobs all along an economically depressed corridor. The total cost of the project might run a paltry $150 to 200 million. But getting the project approved and funded has been slow due to a lack of funding, and opposition by locals who fear change.

The European wood pellet market alone will be roughly $7 billion a year by 2020. The U.S. could supply a big share of that – perhaps as much as $1 billion a year worth of exports. Globally, the opportunity is even greater, with China, Japan, and other countries planning to increase their demand for pellets.

But we’re not going to capture that market share without overcoming the chicken-and-egg problem of shipping infrastructure and logistics. Before they’ll invest billions of dollars in new pellet mill capacity, backers want to see signed offtake agreements with utility buyers and be assured that they’ll have economical transport to European markets. The utilities won’t sign offtake agreements without knowing what the cost and delivery volumes will be. And nobody is going to spend billions on port and rail upgrades without being sure of the demand for those facilities.

This is precisely the sort of project where state and federal leadership could make all the difference, delivering enormous benefits in local jobs and national exports. Unfortunately, our governmental bodies remain in legislative capture by the automobile and oil industries, and haven’t shown much leadership on freight rail and rail-to-port infrastructure that isn’t “shovel-ready.” With tragic short-sightedness, the vast majority of federal transportation infrastructure investment still goes to politically expedient road projects.

Building rail and waterborne transport infrastructure is a no-brainer for America, and it’s high time we made it a national priority. As I have detailed previously, we should be spending on the order of $1 trillion a year on a national infrastructure program, with emphasis on port and rail capacity. Not only could it restore full employment in the short term, but by the time we get it finished decades from now, it will prove to be a critical lifeline safeguarding our economic viability in an age of declining fossil fuels.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.