The Microplastic Invasion: 12 Ways to Minimize Your Exposure

Plastic. It’s ubiquitous. From mountain tops to ocean depths, it’s a part of our everyday lives. Plastic pollution is so widespread now that scientists are dubbing this period in history the “Plasticene Age.”

One of the most versatile, well used and persistent substances that exist on earth, it generally isn’t biodegradable. As it breaks down in the environment it gets smaller and smaller until it infiltrates just about everything in the form of micro- and nano-sized particles.

They’re everywhere. In the air, water, seas, human bodies, dust, food, plants and animals. Finally, the subject of microplastics is hitting the headlines as awareness of the problem escalates.

Even water is packaged in plastic bottles. With billions of bottles of water produced and sold globally every year for people who can afford it, try and escape chlorine-, hormone- and too often, fluoride-laden tap water.

Globally consumption of bottled water is expected to reach 515 billion liters a year by 2027. But, is bottled water as safe as we think it is? A 2018 study found microplastics in 93% of the bottled water tested.

Researchers recently reported the presence of around 240,000 tiny pieces of microplastics in a 1-liter bottle of water. This is 10 to 100 times more than previous studies, which focused on larger particles of plastic.

Particles of seven of the most commonly used plastics were found along with millions of other particles of unknown origin.

The silent invasion

Microplastics can now be found in just about every nook and cranny on Earth, yet they’re virtually invisible to the naked eye.

They’re tiny pieces of plastic, less than five millimeters in length, that originate from a wide range of sources. Particles smaller than 1μm (micron/micrometer) are classified as nanoplastics.

Despite their pervasiveness, not much is known about microplastics and their impacts on our health and the health of the environment as yet.

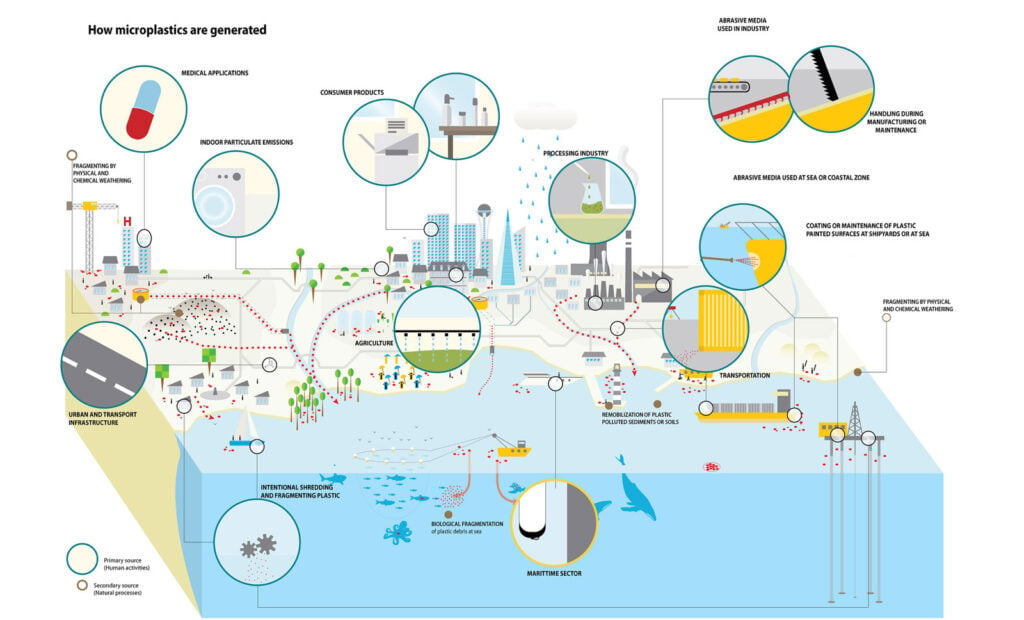

Microplastic is categorized as either primary or secondary microplastic:

- Primary microplastics come from items deliberately manufactured to be small, such as clothing microfibres, microbeads and plastic pellets (known as nurdles) along with microplastics released while washing synthetic clothing.

- Secondary microplastics come from discarded plastic waste such as bags, bottles and packaging, which is said, can take up to 450 years to degrade — although not sure anyone has been able to corroborate the timing!

Every day we’re exposed to microplastics through the air we breathe, what we eat, drink, inhale and even touch.

Microplastic particles can be small enough to cross biological barriers such as the gut, skin, placenta and airways.

Bottle-fed babies are at high risk of exposure to microplastics from baby bottles, but they’ve also been found in breast milk. And, let’s not forget older children who often drink from plastic bottles and pouches.

Millions of tons of plastic waste end up in our oceans every year, where it’s broken down by the action of the waves and sunlight into nanoplastics, which accumulate in marine food chains and habitats such as coral reefs.

Not only are microplastics a major environmental concern, but there’s also growing concern over their impact on human health.

How harmful are they?

Little is known about the effects of microplastics on human health currently, leading to an explosion in research into the issue.

However, despite such limited knowledge, these tiny plastics, which are found in virtually all brands of bottled water, public drinking water supplies (although lower than bottled water), as well as most of the food we eat due to the use of biosludge from water treatment plants and plastic coatings on agricultural chemicals, have already been linked to a myriad of chronic health conditions including:

Increasing evidence suggests that the toxicity of the endocrine-disrupting chemicals that microplastics are made from — e.g. BPA, phthalates and other toxic substances, that they absorb from the environment and concentrate — are enhanced by the size, shape and surface charge of the particles, as well as their abundance.

One study found that toxicity increased by a factor of 10. Such toxins may then be released into the human body, greatly increasing the risk of harm to health.

Microplastics are also providing new and distinct niches for microbial colonies to develop, some of which may be antibiotic resistant.

Microplastics have now been found in our blood, showing they can travel around the body, potentially ending up lodged in our organs.

They can even cross the blood-brain barrier through a process known as transcytosis, where particles can move through lipid (fat) layers like we have in our cell membranes, without being engulfed and destroyed by the cell they’re crossing.

Once in the brain, they’ve been shown in mice to cause cognitive changes similar to those seen in dementia patients.

So great is the problem, it’s been estimated that microplastic contamination cost the U.S. healthcare system nearly $250 billion in 2018.

Reducing our exposure

As the scale of the problem becomes apparent and plastic waste continues to accumulate unabated, scientists are scrabbling to find solutions that range from using magnets to pull microplastics attached to an adsorbent from water, to enzymatic recycling, using genetically modified enzymes to break down plastic into ever smaller molecules that can then be used to create new plastic.

However, research is in its infancy and such techniques have only been used under laboratory conditions to date.

The good news is as awareness of the problem grows so do the number of innovative solutions. One such solution is the Hoola One beach vacuum, which removes microplastic particles up to 0.05 millimeters in size.

Avoiding microplastics completely is probably impossible in the modern world considering their use is so widespread.

Ultimately, we’re not likely to be able to avoid it, so there’s little point worrying about every piece of plastic that we encounter, but we can take steps to reduce our exposure.

- Think about your plastic usage and how you might be able to reduce it e.g. not using throw-away plastic items such as cutlery and straws.

- Substitute single-use takeaway cups and bottles for your own stainless steel, bamboo or glass reusable cups and bottles.

- Recycle plastic rubbish where possible and bin waste when you’re out.

- Buy food packaged in glass or try out your local Fill Up shop where you can use your own containers over and over again.

- Buy a good water filter to remove the microplastics. Reverse osmosis systems are our preferred option as they remove most of the particles, but also the vast majority of chlorine, hormones and fluoride.

- Don’t heat food or liquid in plastic containers, particularly in microwaves, due to the number of particles released into your food.

- When buying clothes, try to buy natural fabrics as opposed to synthetic fabrics, which shed plastic microfibres. Natural fibres can be more expensive so why not check out your local charity shop and do a bit of recycling at the same time?

- Use a washing bag to reduce microplastic pollution when washing synthetic fabrics.

- Air dry clothes rather than using a tumble dryer, which increases the production of microfibers.

- Dust and vacuum (use a vacuum with a HEPA filter) regularly to reduce the accumulation of microplastics found in households.

- Buy plastic-free cosmetics and personal care products. Check the labels for products containing plastic microbeads.

- Ditch teabags and use organic, fairly traded loose-leaf with an infuser or old-fashioned teapot. Yep, you heard that right. Many tea bags contain plastic, which when heated can release billions of microplastics into your tea. Even so-called biodegradable tea bags, you know, the posh silky ones, are made from a type of genetically modified organism plastic and they’re not silk at all!

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.