Speakers At Washington Forum On Drought And Agriculture Ignore Climate Change

Yesterday morning, as high temperatures and drought in the Midwest intensified, the Farm Foundation held a forum to discuss the impact of long term drought on agriculture. Remarkably, until I asked a question about it, the topic of climate change did not come up.

Yesterday morning, as high temperatures and drought in the Midwest intensified, the Farm Foundation held a forum to discuss the impact of long term drought on agriculture. Remarkably, until I asked a question about it, the topic of climate change did not come up.The panel was made up of Matthew Rosencrans, a member of the drought monitoring staff at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; David Anderson, a professor in the Agricultural Economics department at Texas A&M; Jay Armstrong, a farmer and seed salesmen from northern Kansas who sits on the boards of numerous agricultural organizations; and Kitty Smith, an economist and policy expert with the American Farmland Trust. The question and answer period was moderated by former Congressmen Charlie Stenholm (D-TX).

The participants went through their presentations about drought data collection, the effects of drought, and long-term drought planning without once mentioning climate change once. When I asked about it, I was not received warmly.

“They call it weather,” said Mr. Armstrong.

Though he admitted to seeing some increased volatility in the weather, he accused the media of overstating the problem, talking “about what used to be a forest and is now a desert” and not putting enough emphasis on “what used to be a desert and is now a forest.” (Mr. Armstrong should talk to Dr. Craig Allen, who thinks that “rising temperature is going to drive our forests off the mountains.”)

Congressman Stenholm didn’t seem too pleased with my question, judging by his disapproving stare.

Mr. Anderson, the economist from Texas, described the devastating effects of last year’s Southwestern drought. Anderson estimated the economic losses in the agriculture sector from that drought to be in the billions; almost $4.5 billion in corn, wheat, hay, and cotton and more than $3 billion in livestock.

And as that drought unfolded, leading climate scientists warned about the influence of anthropogenic climate change on the intensifying crisis.

Texas A&M, climate scientist Andrew Dessler said last August that “there is absolutely no way you can conclude that climate change is not playing a role here. I’m quite surprised that anyone would even suggest that.” Texas climatologist Katherine Hayhoe also recently explained that “our natural variability is now occurring on top of, and interacting with, background conditions that have already been altered by long-term climate change.”

In addition, NASA climatologists, including James Hansen, released peer-reviewed research concluding that the Texas heat wave was “a consequence of global warming because their likelihood was negligible prior to the recent rapid global warming.” The future is even more worrisome — see “James Hansen Is Correct About Catastrophic Projections For U.S. Drought If We Don’t Act Now.

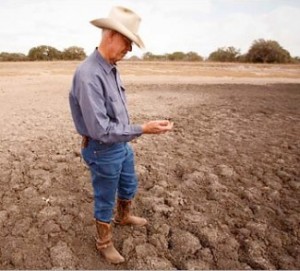

Today, the Midwest and Great Plains region is entering a severe drought. As temperatures continue to rise and rainfall is nowhere on the horizon, the threat to crops intensifies:

“Yesterday, USDA released its weekly crop condition report and the areas of declining production predictably match the areas of drought. In particular, Illinois and Indiana, two large Midwest grain producing states that were challenged by poor planting conditions in the early spring, now face increased lack of moisture.”

Ironically, the frequency of extreme rainstorms in the Midwest that damage crops and cause flash flooding have doubled in the last 50 years, according to a survey of rainfall data by the Rocky Mountain Climate Organization.

The increasingly dire influence of human-induced climate change on the agricultural sector has encouraged some to speak up. In April, the former president of the American Corn Grower’s Association said that farmers are “at the front lines of global warming — it’s a grave threat to rural livelihoods and quality of life. That’s why I support EPA policies to cut global warming pollution from automobiles and power plants.”

In spite of the mounting evidence and concern within the agricultural sector, it is astonishing that no one discussed climate change in a forum called “How Drought Reshapes Agriculture and Food Systems.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.