Nuclear Restart Generates Power, Protest in Japan

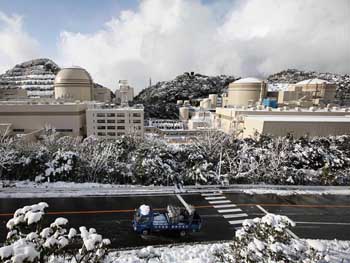

The restart of one reactor at the Ohi nuclear plant in western Japan, seen to the right, comes ahead of safety measures that were promised in the wake of the Fukushima Daiichi disaster last year. Thousands of anti-nuclear protestors, shown below, flooded central Tokyo on Monday.

The restart of one reactor at the Ohi nuclear plant in western Japan, seen to the right, comes ahead of safety measures that were promised in the wake of the Fukushima Daiichi disaster last year. Thousands of anti-nuclear protestors, shown below, flooded central Tokyo on Monday.Every Friday evening they gather before Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda’s residence.

The first rally in March was modest: a few hundred citizens joined against nuclear power, marking the anniversary of the earthquake- and tsunami-triggered Fukushima Daiichi disaster a year earlier. But in recent weeks, since Noda decided to restart two of Japan’s 54 idled nuclear reactors, the protest has swelled into a mass demonstration blocking the streets of Japan’s political center.

Building on their Friday night momentum, protestors on Monday staged their largest rally yet, with tens of thousands of people congregating at Yoyogi Park, and then marching in three groups through the capital.

This rare display of public discontent by the Japanese, bringing together citizens from all walks of life, shows no signs of waning, exposing how deeply the nation is divided over the form of energy that until recently powered one-third of Japan’s economy.

“Never in my 39 years of my life have I ever tried to voice my views out loud like this,” said Hitoshi Iwata, a Tokyo office worker who took to the streets after learning of the event through social media. “I expected the Fukushima case would turn society away from nuclear power,” he said. “But when things started to move on the contrary, the sense of disappointment was so strong I felt a compelling need to voice my protest.”

But there are no easy answers for Japan. The nation has no known fossil-fuel reserves of its own, and began relying heavily to nuclear power as a home-grown resource after the global oil shocks of the 1970s. The nation’s faith in the safety of its nuclear fleet was shattered when the March 11, 2011 earthquake and tsunami touched off the crisis at Fukushima. Since then, Japan has been ramping up fossil-fuel imports, aggressively promoting renewables and conservation, and trying to plot a new energy future.

But there are no easy answers for Japan. The nation has no known fossil-fuel reserves of its own, and began relying heavily to nuclear power as a home-grown resource after the global oil shocks of the 1970s. The nation’s faith in the safety of its nuclear fleet was shattered when the March 11, 2011 earthquake and tsunami touched off the crisis at Fukushima. Since then, Japan has been ramping up fossil-fuel imports, aggressively promoting renewables and conservation, and trying to plot a new energy future.While debate continues on a long-term plan, though, Noda concluded Japan couldn’t make it through summer without some measure of atomic energy—a decision that now has driven opposition into the streets.

Nuclear Restart

By May of this year, all of Japan’s nuclear reactors had been shut down, as governors used the power available to them under law to refuse to sign off on restart of any power plant after routine maintenance. Local officials argued that major changes were needed to ensure the safety of nuclear power in the earthquake-prone nation, after the March 11, 2011, Tohoku temblor and tsunami that inundated Fukushima Daiichi, triggering explosions and radioactive releases that rendered surrounding communities uninhabitable.

But as cleanup continues at Fukushima, fear of a national energy crisis grows. The government estimated that Kansai Electric, the company that provides power to Japan’s second most populous region, could face a shortfall of nearly 15 percent this summer if all the nuclear plants stayed idle. With 50 percent of its power generated by 11 atomic reactors, Kansai in western Japan was the nation’s most nuclear-dependent region before last year. Its business community breathed a sigh of relief after Kansai Electric, with Noda’s approval, on July 1 restarted one of the reactors at Ohi power plant in Fukui Prefecture on the Sea of Japan. A second reactor at Ohi is expected to be back online later this month. Officials still fear a summer energy crunch, and have asked the people of Kansai to cut back power usage by 10 percent.

Imports of fossil fuel have skyrocketed, with shipments of liquefied natural gas (LNG), mostly from Asia, hitting a record high of 83.18 million tons in the fiscal year that ended in March. The $66 billion in fuel costs pushed Japan into a trade deficit for the first time since 1980.

Japan hopes that as early as 2016 it can begin importing LNG from North America, where natural gas has been selling for about one-quarter the price of LNG on the Asian markets. But the wait could be longer because building huge export terminals to supercool and concentrate natural gas for shipment overseas is highly controversial in the United States.

Japan’s utilities posted record losses last year due to rising spending on fuel purchases, coupled with the cost of maintaining the idle nuclear power plants. Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), which has needed massive injections of government money to keep it afloat, still faces an estimated $100 billion in decommissioning and compensation costs at Fukushima. The nation’s largest utility now is seeking regulatory approval to raise consumer electricity bills as much as 10 percent, despite public outcry that TEPCO hasn’t done enough to cut costs. The government will decide whether to approve the request by the end of July.

Protestors, meanwhile, argue that safety is taking a back seat to economic considerations. The Ohi plant’s safety is based only on provisional standards; promised safety measures-higher sea walls, filters, and a quake-proof building-won’t be ready for many months. To address concerns of communities surrounding the Ohi plant, the evacuation zone in the event of an accident has been expanded to include neighboring prefectures, but there is still no accompanying evacuation plan. Residents worry an accident could contaminate the region’s largest freshwater source, Lake Biwa, and seismologists have warned that authorities failed to take into account active fault lines around Ohi, including one small fault that runs directly below one of the reactors.

“I’m so angry that Mr. Noda hasn’t taken on the perspective of the citizens and local residents,” said Yukiko Kada, governor of Shiga Prefecture in Kansai. She told a news conference that she and other governors from the region near the reactors were “practically bullied” for their opposition to the restart. The central government, Kansai Electric, and other business interests warned that if the power plants were not restarted, local officials would bear the blame for any power blackouts.

Rallying for Renewables

With renewable energy accounting for only one percent of the country’s total electricity output, Japan is taking new steps to promote alternative energy sources and make sure that not a single watt of power is wasted as the summer heat wave approaches.

Starting this month, a new feed in-tariff requires Japan’s utilities to buy electricity from renewable energy sources at above-market rates. The program has served as an incentive to for businesses to get in on the solar and wind energy game.

SoftBank, Japan’s third largest mobile phone company, plans to operate renewable energy plants in at least 11 locations nationwide, and aims to build the nation’s largest solar plant in Kyoto. Masayoshi Son, SoftBank’s founder and chairman, often described as the richest man in Japan, has emerged as an outspoken advocate of renewable energy since the Fukushima disaster.

The Japan Electric Power Exchange, established in 2003 to allow wholesale trading of electricity, an early effort to curb the monopoly power of the nation’s electric utilities, has taken on the role of creating a market for renewables: It has started trading small amounts of surplus electricity generated by businesses’ off-grid power systems, as well as solar and other renewable energy sources.

Meanwhile, Kansai Electric, which has faced criticism for the restart of the Ohi reactor, has become the first Japanese company to attempt to use market incentives to encourage consumers to save energy. In its “nega-watt” trading scheme, Kansai will use an auction process to “buy” amounts of electricity that its 7,000 large corporate customers pledge to save during the peak-demand weeks between July and September.

Trade Minister Yukio Edano, who oversees the energy sector, says the government’s mid-term policy to reduce reliance on nuclear energy “has not changed at all.” Last month, the government announced three options for a new energy policy to replace its 2010 goal of expanding nuclear power’s share of the nation’s electricity generation from 30 percent to 50 percent by 2030. The new options include eliminating nuclear altogether, or reducing dependence to 15 percent or 20-25 percent by 2030, although the alternative plans do not clarify how nuclear waste disposal would be handled, or how Japan would meet its international pledge to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions to 25 percent below 1990 levels by 2020.

An independent analysis by the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies concluded it would be economically feasible for a nuclear-free Japan to achieve an 80 percent CO2 reduction by 2050. But it would require technological advances, particularly in carbon capture and storage technology, even more dramatic curbing of energy consumption and aggressive deployment of renewable energy, and success in securing dramatically increased natural gas supply.

Jusen Asuka, director of the climate change group at IGES argues that global warming should not be an excuse for nuclear power. “People often talk of the ‘devil’s choice,’ but this shouldn’t be about a trade-off.” Asuka said there are many ways to work toward a nuclear-free society while addressing global warming; the issues are cost, and society’s will. “I think it’s economical, and ethical, to start making the effort now.”

Options on Japan’s future energy plan will be debated in public hearings, and nationwide polls are planned before the government makes a final decision in August.

And there are the voices outside the prime minister’s residence on Friday nights.

If such protests seem unusual for Japan, it is not the first precedent broken as the nation grapples with the Fukushima’s political fallout. Only days after Kansai Electric pulled the control rods out of the reactor core at Ohi, allowing nuclear fission to resume, the results of an inquiry into the disaster were made public by the first independent commission ever chartered by Japan’s legislative body, the Diet. It was a rallying cry for change.

“What must be admitted—very painfully—is that this was a disaster ‘Made in Japan,’ ” wrote Kiyoshi Kurokawa, chairman of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission. “Its fundamental causes are to be found in the ingrained conventions of Japanese culture: our reflexive obedience; our reluctance to question authority; our devotion to ‘sticking with the program’; our groupism; and our insularity … In recognizing that fact, each of us should reflect on our responsibility as individuals in a democratic society.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.