Heat Waves and Climate Change

There has been a remarkable run of record shattering heat waves in recent years, from the Russian heat wave of 2010 that set forests ablaze to the historic heat wave in Texas in 2011 and the Summer in March in the U.S. Midwest in 2012. These events typify the ongoing trend driven by climate change.

There has been a remarkable run of record shattering heat waves in recent years, from the Russian heat wave of 2010 that set forests ablaze to the historic heat wave in Texas in 2011 and the Summer in March in the U.S. Midwest in 2012. These events typify the ongoing trend driven by climate change. Climate change is already affecting extreme weather. The National Academy of Sciences reports that the hottest days are now hotter. And the fingerprint of global warming behind this change has been firmly identified. Since 1950 the number of heat waves worldwide has increased, and heat waves have become longer.

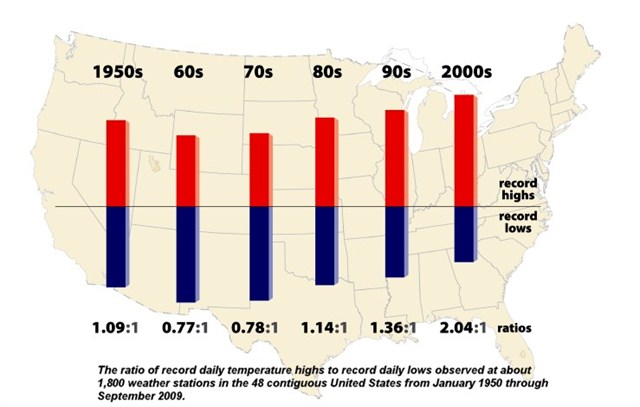

The hottest days and nights have become hotter and more frequent. In the past several years, the global area hit by extremely unusual hot summertime temperatures has increased 50 fold. Over the contiguous United States, new record high temperatures over the past decade have consistently outnumbered new record lows by a ratio of 2:1. In 2012, the ratio for the year through June 18 stands at nearly 10:1.

Though this ratio is not expected to remain at that level for the rest of the year, it illustrates how unusual 2012 has been, and how these types of extremes are becoming more likely.

The significant increase in heat extremes we have witnessed associated with a small shift in the global average temperature is consistent with climate change. The percentage change in the number of very hot days can be quite large.

Global warming boosts the probability of very extreme events, like the recent Summer in March episode in the U.S. in which thousands of new record highs were set, far more than it changes the likelihood of more moderate events.

Higher spring and summer temperatures, along with an earlier spring melt, are also the primary factors driving the increasing frequency of large wildfires and lengthening the fire season in the western U.S. over recent decades. The record breaking fires this year in the Southwest and Rocky Mountain Region are consistent with these trends.

The impact of these changes can be devastating. The drought, heat wave and associated record wildfires that hit Texas and the Southern plains in the summer of 2011 cost $12 billion.

Looking Forward:

Confidence has risen in computer model projections of future changes in hot extremes because recent observations are consistent with the results of past model predictions.

Models predict that the same summertime temperatures that ranked among the top 5% in 1950-1979 will occur at least 70% of the time by 2035-2064 in the U.S. if global emissions of greenhouse gases grow at a moderate rate (as modeled under the IPCC SRES A2 scenario). Such a growth rate would require a decline from the current high rate of growth.

The South, Southwest, and Northeast may be especially prone to large increases in unusually hot summers. Parts of the South that currently have about 60 days per year with temperatures over 90 degrees are projected to experience 150 or more days a year above 90 degrees by the end of this century.

By the end of this century, a once every 20 year heat wave is projected to occur every other year.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.