EU heads towards mandatory Eco-labelling!

EU demands for customers to know the environmental impact of household products could force brands to adopt eco-labels soon – whether they like it or not.

EU demands for customers to know the environmental impact of household products could force brands to adopt eco-labels soon – whether they like it or not.Brussels policy-makers are planning a far-reaching expansion of mandatory labelling and “eco-design” requirements in the European Union, as part of a push to cut carbon dioxide emissions, resource use and waste.

The existing labelling scheme for energy-using products such as washing machines and refrigerators will be extended to all manufactured consumer goods, from windows and bathtubs to shoes and clothing. The EU’s voluntary “flower” or “eco-label”, which can be found on consumer goods such as detergents and shampoos with a low environmental impact, will also be simplified in an effort to cover more products.

“The need to address unsustainable trends and move towards more sustainable patterns of production and consumption is more pressing than ever,” says an early draft of the European Commission’s “sustainable consumption and production” action plan, published in May. Products that do not reach a minimum level of environmental performance will be barred from the EU market, raising concerns from some companies, which say the market, not regulators, should decide green standards for products.

Such restrictions are not likely to take effect any time soon, as the proposals still need to pass through the EU’s law-making machine, a process that can take anything from nine months to two years.

While the precise method of determining the minimum eco criteria still must be hammered out, priority “will be given to the reduction of climate change emissions, to the improvements in the efficiency of the use of natural resources and energy, and to the phasing out of the use of hazardous and endangered materials”, the draft says.

In addition to minimum standards, benchmarks will also be set according to the “best performers” in each category, but these will be based on voluntary industry initiatives, according to the draft.

Low carbon diet

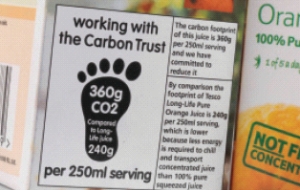

Tesco, the UK’s largest retailer, appears to have got a head start in the coming labelling fray. The company has launched a trial carbon-labelling scheme on 20 of its own detergents and light bulbs, as well as on two food items: potatoes and orange juice. The goods will be labelled based on their CO2 output across their life-cycle, from manufacture to consumption, using a methodology developed with the UK government-funded Carbon Trust.

The EU’s labelling plan is “absolutely the right thing”, say Ian Hutchins, Tesco’s European affairs manager. Hutchins says Tesco is responding to growing consumer demand for more green goods and hopes the carbon-label campaign will raise awareness so that the scheme can be expanded. There are currently no equivalents to the Carbon Trust to assist companies in other European countries develop carbon labels.

Not all retailers support the plans. The European Food and Drink Industry Association said in its response to the commission’s plan that it “does not support discrimination between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ products on purely environmental grounds”.

As for worries about higher costs for green goods, industry in general has so far been relatively silent on the matter. Hutchins believes costs will come down in time as green products become more popular. And the commission is including financial incentives such as tax breaks and more green public procurement in its action plan to further assuage industry concerns about a possible drag on profits.

Will shoppers get it?

More worrying for companies and consumer groups alike is the confused shopper.

Europe’s products abound with labels displaying nutritional information or touting the sustainability of a product. The emphasis should be on simplicity, and Europe’s policy-makers should have “a more realistic understanding of consumers as they actually are, and not as we would wish they were”, says Jim Murray of the EU consumer organisation BEUC.

Advertisers meanwhile are concerned about separate calls by members of the European Parliament, led by the UK Liberal Democrat Chris Davies, to devote at least 20 per cent of billboard and other advertising space to informing consumers about the fuel efficiency and CO2 output of vehicles.

Davies’s proposal has not made much headway in EU circles, and cars and the transport sector in general will not be directly included in the sustainable consumption and production action plan. But it is clear that Brussels has embarked on a far-reaching green labelling agenda.

Companies will have to adjust, and to decide whether to take voluntary initiatives or to comply only with the minimum criteria.

“You’ll always have companies that stretch themselves beyond what policy-makers are asking for, and ones which are simply following what is being asked from them,” says Tom Himpe, a London-based strategic planner for corporate brands and author of “Advertising Is Dead, Long Live Advertising”.

Some companies have already cried foul. The commission faces criticism from a number of industries. Chemicals makers in particular appear squeamish about the prospect of more regulations after having emerged only recently from an intense lobbying campaign over the EU’s new Reach regime for registering, evaluating, authorising and restricting chemicals.

For companies that want to lead rather than follow on carbon labels, time is running out.

Energy drain

35-40 per cent – the percentage of environmental impacts of all products that energy-using products like home appliances account for.

Almost two-thirds of environmental impacts are caused by products that do not use energy directly from the mains. It is these products – such as windows and shoes – that the European Commission’s plans will cover.

Source: Sustainable Production and Consumption and Sustainable Industrial PolicyAction Plan draft

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.