China Is Taking Control Of Asia's 5 Great Rivers That Flow Out Of Tibet

China’s engineers are damming or diverting the five great rivers that flow out of Tibet and into neighbouring countries. ITS vast ice sheets and monsoon run-off make the Tibetan plateau one of the largest sources of fresh water on an increasingly thirsty planet. It supplies 1.3 billion people with water for irrigation and drinking, and offers the promise of unparalleled hydropower. But who owns this water? As China looks to claim the vast flows that emerge from the water tower of Asia, what of the rights of its downstream neighbours?

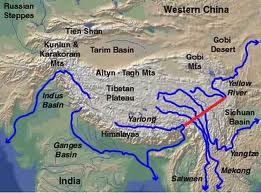

China’s engineers are damming or diverting the five great rivers that flow out of Tibet and into neighbouring countries. ITS vast ice sheets and monsoon run-off make the Tibetan plateau one of the largest sources of fresh water on an increasingly thirsty planet. It supplies 1.3 billion people with water for irrigation and drinking, and offers the promise of unparalleled hydropower. But who owns this water? As China looks to claim the vast flows that emerge from the water tower of Asia, what of the rights of its downstream neighbours?With hydro-engineers moving in, questions like these are fast becoming incendiary geopolitics. China is centre stage: it has plans to dam or divert each of the five great rivers that emerge from Tibet’s high plateau before tumbling into neighbouring countries - the Indus, Brahmaputra, Irrawaddy, Salween and Mekong (see map). The projects have sparked simmering disputes between China and its neighbours.

The starting gun in a race to control Tibet’s rivers may have been fired with a court order from India’s Supreme Court last month, calling for work to begin on canals that will link many of India’s largest rivers. The scheme’s lynchpin is a 400-kilometre-long canal that will divert water from the Brahmaputra to the Ganges to irrigate water-starved fields 1000 kilometres to the south (see “India redraws its river map”).

The court decision is partly a reaction to nascent Chinese schemes to dam and divert the Brahmaputra further upstream in Tibet. For now, the Brahmaputra remains one of the planet’s last great untamed rivers. That may soon change. In addition to the Indian diversion plan, Chinese engineers want to tap the river in the Tsangpo canyon. There they could build two hydroelectric plants, each delivering twice the power of the Three Gorges dam on the Yangtze, currently the world’s largest dam. Even further upstream, engineers have drawn up plans to divert up to 40 per cent of the river’s flow to irrigate crops on China’s northern plains.

The plans are making Bangladesh and India, which both lie downstream on the Brahmaputra, very nervous. India faces a water crisis, and sees the Brahmaputra as its largest untapped water source. But the real victim could be Bangladesh, which relies on the river for two-thirds of its water, much of it for irrigation during the long dry season. Nearly 20 million Bangladeshi farmers depend on the river to water their crops.

The competing projects could lead to a resource conflict between India and China, and an environmental catastrophe for Bangladesh, Robert Wirsing of Georgetown University School of Foreign Service in Qatar warned a conference on water security held in Oxford, UK, last week.

Until recently, China mostly dammed rivers flowing within its borders. But to meet soaring demand for energy and irrigation, its engineers have moved on to international rivers. Already, China has completed a series of dams on tributaries of the Brahmaputra. The first on the river’s main stem, the $1-billion Zangmu dam, will be completed in 2014. Next up could be the Tsangpo canyon dams: Motuo, which would deliver 38 gigawatts, and Daduqia, at 42 gigawatts.

It is not just water flowing into India and Bangladesh that China has in its sights. Its other neighbours are also growing restive. The latest flashpoint is the Myitsone dam being built by China on the Irrawaddy in northern Burma. Burmese generals approved the scheme three years ago, even though 90 per cent of the electricity from the 6-gigawatt plant will go to China. But late last year, the new reformist government suspended construction after dozens of people were killed during clashes between the army and locals, whose villages would be flooded.

The political situation in Burma makes the ultimate fate of Myitsone and 12 other dams planned by China in Burma - six on the Irrawaddy and six on the Salween - unclear. Many of the proposed dams are in a remote area designated a World Heritage Site because of its unique forest and freshwater ecosystems.

Further west, Chinese construction of the 7-gigawatt Bunji dam on the Indus in northern Pakistan has angered India, which claims the territory. Locals are also fearful, since the dam is close to the epicentre of an earthquake that killed more than 100,000 people in 2005.

The hydro-politics are fierce. But what is the evidence that such dams do harm? After all, many argue that hydroelectricity is vital for countries like China and India to develop their economies using low-carbon energy.

Published studies are thin on the ground, but after work on the Myitsone dam was suspended, it emerged that an unpublished 900-page environmental impact assessment commissioned by the Chinese had recommended against the dam because it would flood important forest ecosystems.

Published studies are thin on the ground, but after work on the Myitsone dam was suspended, it emerged that an unpublished 900-page environmental impact assessment commissioned by the Chinese had recommended against the dam because it would flood important forest ecosystems.The impact on Bangladesh of the Indian plan to divert the Brahmaputra has been modelled by Edward Barbier of the University of Wyoming in Laramie and Anik Bhaduri of the International Water Management Institute in Delhi, India. They warn that “a 10 to 20 per cent reduction in the river’s flow could dry out great areas [of Bangladesh] for much of the year”.

Without the flow of fresh water, salt from the Bay of Bengal would invade the large river delta, causing “an environmental catastrophe”.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.