50th Anniversary Of 'Silent Spring' ~ Importance Of Environmental Regulations

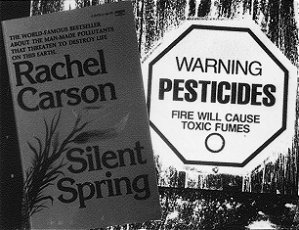

This year marks the 50th Anniversary of the release of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, a book often credited with launching the modern environmental movement. As we celebrate recent vital regulations, from new fuel economy standards to carbon pollution standard, it’s important to look back on how one book moved the American public to realize the importance of environmental protection and called the government to action.

This year marks the 50th Anniversary of the release of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, a book often credited with launching the modern environmental movement. As we celebrate recent vital regulations, from new fuel economy standards to carbon pollution standard, it’s important to look back on how one book moved the American public to realize the importance of environmental protection and called the government to action.In Silent Spring, Rachel Carson broke down four years of research on the harmful impacts of DDT, a pesticide first used to kill malaria-causing insects for U.S. troops during World War II and later used to kill agricultural pests. The generous use of DDT on crops killed far more than the targeted insects and remained in the environment even after dilution with water. The consequence? DDT entered into the food chain and built up in fatty tissues of animals, leading to cancer and genetic damage. It was dangerous for birds and animals and threatened the entire globe’s food chain. Silent Spring’s most famous chapter detailed a town in which DDT’s effects had “silenced” all animals and residents. Importantly , however, Carson did not call for a complete ban of DDT.

She wrote:

“It is not my contention that chemical insecticides must never be used. I do contend that we have put poisonous and biologically potent chemicals indiscriminately into the hands of persons largely or wholly ignorant of their potentials for harm. We have subjected enormous numbers of people to contact with these poisons, without their consent and often without their knowledge.”

Even with this explanation, the chemical industry responded forcefully. Monsanto, for example, published a brochure titled “The Desolate Year,” warning of famine and disease without the use of DDT. Yet Carson’s meticulous research, with 55 pages of notes and list of experts, withstood the attacks and was recognized by President John F. Kennedy, who asked the President’s Science Advisory Committee to research Carson’s claims. DDT was eventually banned in 1972. For the American public, it raised far bigger questions about more than just DDT. If DDT had this dangerous impact on humans and animals, what other poisons were unknowingly lurking in neighborhoods, water, and food?

The threat of invisible pollutants added to the pollution problems Americans could see and feel in their cities during rapid industrialization. In the 1940s and 1950s, smog had blanketed major cities and sewage and industrial waste floated in U.S. rivers. In 1948, pollutants trapped over the industrial city of Donora, Pennsylvania killed twenty and permanently injured hundreds.

In these conditions, the publication of Silent Spring lit a spark among environmentalists and the general public alike to address industrial pollution, both the visible and invisible. As the decade went on, teach-ins, TV shows, and various forums educated the public on threats the humans and the environment faced from pollution. Then in June 1969, the Cuyahoga river caught on fire due to oil slicked debris and pollution from decades of industrial waste. The flaming river was a powerful symbol of the costs of unchecked industrialization, and Americans demanded government action to clean up pollution.

At the end of 1969, President Nixon and Congress sprang into action to address public concerns on the environment. Congress passed the 1969 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) that declared a national environmental policy, promoted efforts to protect the environment and public health, and encouraged deeper understanding of the threats humans and ecosystems faced. Importantly, NEPA called for the federal government to complete environmental impact statements (EIS) for all federal project planning. NEPA also established the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) to advise the President on environmental issues.

On New Year’s Day 1970, Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), stating that he was:

“convinced that the 1970s absolutely must be the years when America pays its debt to the past by reclaiming the purity of its air, its waters, and our living environment. It is literally now or never.”

He declared the signing his “first official act of the decade.” Then on February 10th, he presented Congress with a 37-point environmental action message and requested 4 billion dollars to improve federal water and air pollution problems. Later that year, Americans showed their public and bipartisan support for environmental protection on April 22nd 1970, when 20 million Americans participated in the first Earth Day, holding teach-ins and peaceful demonstrations around the country. Senator Gaylord Nelson (D-Wis) and Congressman Paul McCloskey (R-Calif) cosponsored a bipartisan event in Washington.

As the year progressed, President Nixon became more convinced that a new independent agency was necessary to coordinate the environmental work across the administration. The President’s Commission on Executive Reorganization helped stitch together the various air, water and other environmental quality programs and departments that eventually became the EPA. The core programs were the HEW National Air pollution Control Administration (NAPCA) and Interior’s Water Quality Administration (FWQA), that were created in response to a wide range of environmental problems, including toxic smog in Los Angeles, untreated sewage, industrial waste, dying rivers and lakes.

On December 2nd, 1970, the Environmental Protection Agency opened with Assistant Attorney General William D. Ruckelshaus at the reins. By the end of the month, Congress had passed the Clean Air Act, giving the EPA the authority to establish national air quality standards, national standards for significant new pollution sources, and facilities emitting hazardous substances. With NEPA and the Clean Air Act as bookends to 1970, President Nixon and the 91st Congress paved the way for the vital health standards that protect Americans today. Two years later, the EPA issued a ban on DDT, based on research of DDT’s effects on wildlife and the potential human health risks. As a direct result, the Eagle population, which was dramatically affected by DDT, has rebounded from just over 400 pairs of bald eagles in the lower 48 states to now more than 4,000

Silent Spring’s impact was much greater than the ban on DDT. Carson’s book made Americans realize that we need regulatory bodies, like the EPA and the Food and Drug Administration to protect us in cases when we cannot realistically protect ourselves. We could not simply rely on enterprising reporters like Carson to do the research and lobby the government to ban toxins. And the average American does not have the resources, expertise, or time to check every glass of water their family drinks for toxins or ensure the air around schools is safe every single day. They need someone to monitor their water and air consistently. They need someone to read every study to know what is safe for their bodies. And they need someone to work with the companies and power plants when their development endangers public health.

Some members of Congress don’t agree with that. Currently, House Republicans are trying to push through H.R. 3409 through the House, which would block clean water and Clean Air Standards, remove the endangerment finding for greenhouse gases, prevent regulations on all greenhouse gas with limited exceptions, negate the new tailpipe standards, and threaten existing tailpipe standards. The bill takes non-partisan issues, such as clean air and clean water, and politicizes them — opening up new threats to public health and the environment.

Protecting the environment and public health began as a bipartisan effort to protect all Americans. That is the legacy that Rachel Carson began, and a legacy that needs to continue to keep Americans safe today.

Arpita Bhattacharyya is Research Assistant to Distinguished Senior Fellow Carol Browner at the Center for American Progress.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.