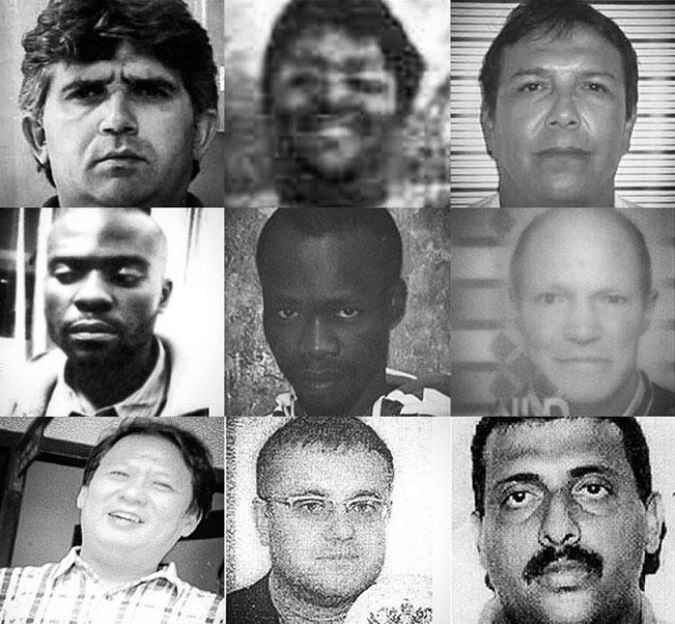

These are the faces of the world's most wanted environmental fugitives

It’s the middle of the night in northern Tanzania, November 2010. Out of the black arrive trucks carrying a most unusual cargo. They stop before a gray-paneled Qatar Air Force plane, disgorging a diverse collection of rare and exotic fauna: six oryx, 68 Thomson’s gazelle, two impalas, three elands, Lapet-faced vulturals, sual cats and 10 small deer-like creature called dik-diks. Then came the jewel: four giraffes.

Animal smuggling is a treacherous, bloody business. And many of the creatures, one conspirator later testified in Tanzanian court, had died en route, including three giraffes. Those that remained had arrived at the entryway to the shadowy world of animal trafficking. These animals, spanning 14 species and numbering more than 110 in all, are believed to have reached Qatar for sale to oligarchs with a taste for exotic creatures.

To be sure, East African animals disappearing into global smuggling rackets isn’t anything unusual, but this case was unique for the fact that it made it to trial, generating days of court testimony and press coverage. The public was scandalized: How could foreigner allegedly infiltrate the national parks, plunder natural resources and avoid detection? A resolution, however, was never reached. Alleged mastermind Ahmed Karman, a 32-year-old Pakistani whose passport was confiscated upon his arrest, disappeared during the middle of the trial.

Now, months later, Karman has emerged once more — but in a very different capacity. Karman earned a spot on a new list compiled by Interpol, the international police agency, naming the world’s most wanted environmental fugitives. It’s populated by the likes of an Indonesian logger, a Dutch wildlife trafficker, an Italian man accused of transporting and discharging toxic waste, a Zambian elephant poacher. The list provides a glimpse into the under-reported world of alleged environmental crime, illustrating how seemingly disparate criminal enterprises, from gun trafficking to drug running to animal smuggling, can commingle.

There’s big money in environmental crime, which includes the illegal exploitation of wildlife and natural resources — like clandestinely chopping down acres of Amazon forest for sale on the timber market. Environmental crime is worth up to $213 billion annually, according to a recent Interpol report that found it’s stewarded by “sophisticated transnational organized environmental crime” rings.

“Wildlife crime is no longer an emerging issue,” the report continued. “… It is a rapidly rising threat to the environment, to revenues from natural resources, to state security and to sustainable development.”

A confluence of factors — including poverty, terrorism, incompetent governance and corruption — has made environmental crime one of the world’s most lucrative and difficult-to-detect trades. “Illegal trade in wildlife can involve complex combinations of methods, including trafficking, forgery, bribes, use of shell companies, violence and even hacking of government websites to obtain or forge permits,” the report said. It added: “The more typical and easier way, however, is simply to bribe corrupt officials.”

The figures at the top these rings are neither notorious nor widely-known. In fact, an online survey of the nine names on Interpol’s list will reveal few newspaper clippings or arrest warrants. They instead represent what Interpol calls a new breed of criminals — with unfamiliar faces and unfamiliar trades, but profit margins similar to other unsavory activities. “Environmental crime is number three or four in terms of profit,” Interpol’s Davyth Stewart, a criminal intelligence officer, told National Geographic. “It’s right up there with drugs, arms, and human trafficking. It certainly is in the same ballpark and makes it very attractive to organized criminals.”

One such group mentioned in the report is the Somalian Islamic militant group al-Shabab. Their environmental crime facilitates their entire operation. The millions of dollars it draws from exploiting charcoal sloshes into its general fund, which it leverages to arm fighters, kidnap people for ransom and plan attacks to broaden its grip on the national charcoal industry. Somalia’s charcoal trade is worth $250 million per year — one-third of which is funneled to al-Shabab, according to Foreign Affairs. That charcoal then finds its way into Gulf cafes, where patrons smoke shisha using illicit charcoal.

“Al-Shabab’s role in the Somali charcoal trade is significant,” wrote Tom Keatinge in Foreign Affairs. “… It benefits at every stage of the trade. For example, the group controls most of the hinterland transport network for the product and is estimated to earn more than $25 million per year through taxes on it. Some claim that charcoal is the largest contributor to the group’s war chest.”

The same forces that gave rise to al-Shabab — corruption and intimidation — have also fueled other environmental criminals though their crimes are sometimes difficult to detect. Documents are forged. Officials bribed. Fugitives like Ahmed Karman, the giraffe smuggler, swoop into a foreign country, steal truckloads of exotic animals, and disappear once more into the night.

“In terms of the crimes, the context is different,” Stewart told National Geographic. “But the methods of concealment — forging documents, using corporate structures, or hiding proceeds — these are the same.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.