Ocean 'dead zones' now top 400, experts find

U.N. report warns of nitrogen runoff killing fisheries. ‘We could end up with no crabs, no shrimp, no fish,’ study co-author warns

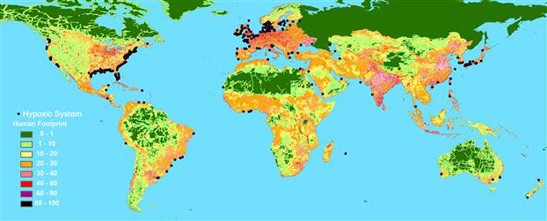

WASHINGTON - Like a chronic disease wasting a body, ocean “dead zones” with too little oxygen for marine life are spreading around the globe, researchers reported Thursday.

The experts counted 405 dead zones in 2007 — a third more than their 1995 survey.

“The number of dead zones has approximately doubled each decade since the 1960s,” the researchers wrote in the journal Science.

“We have to realize that hypoxia is not a local problem,” study co-author Robert Diaz said of the oxygen-depleting trend. “It is a global problem and it has severe consequences for ecosystems.”

“It’s getting to be a problem of such a magnitude that it is starting to affect the resources that we pull out of the sea to feed ourselves,” added Diaz, who is with the Virginia Institute of Marine Science.

“If we screw up the energy flow within our systems we could end up with no crabs, no shrimp, no fish. That is where these dead zones are heading unless we stop their growth,” Diaz said.

The newest dead areas are being found in the Southern Hemisphere — South America, Africa, parts of Asia — Diaz and co-author Rutger Rosenberg reported.

The dead zones covered an area of 95,000 square miles in 2007. The largest U.S. dead zone is at the mouth of the Mississippi River and this summer covers some 8,000 square miles, about the size of New Jersey.

Earth’s largest dead zone is in the Baltic Sea, the researchers said, and experiences hypoxia year-round.

Some of the increase is due to the discovery of low-oxygen areas that may have existed for years and are just being found, Diaz said, but others are newly developed.

Fertilizers, fuel, sewage blamed

Oceans may look pristine but experts warn that life below the sea could collapse. Click through this slideshow by click on the picture to the right to see the threats listed in a 2003 report by experts with the Pew Oceans.

Oceans may look pristine but experts warn that life below the sea could collapse. Click through this slideshow by click on the picture to the right to see the threats listed in a 2003 report by experts with the Pew Oceans.Pollution-fed algae, which deprive other living marine life of oxygen, is the cause of most of the world’s dead zones. Scientists mainly blame fertilizer and other farm runoff, sewage and fossil-fuel burning.

Diaz and Rosenberg, of the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, conclude that it would be unrealistic to try to go back to pre-industrial levels of runoff.

“Farmers aren’t doing this on purpose,” Diaz said. “The farmers would certainly prefer to have their (fertilizer) on the land rather than floating down the river.”

He said he hopes that as fertilizers become more and more expensive farmers will begin seriously looking at ways to retain them on the land.

New low-oxygen areas have been reported in Washington state’s Samish Bay, Yaquina Bay in Oregon, prawn culture ponds in Taiwan, the San Martin River in northern Spain and some fjords in Norway, Diaz said.

A portion of Big Glory Bay in New Zealand became hypoxic after salmon farming cages were set up but began recovering when the cages were moved, he said.

A dead zone has been newly reported off the mouth of the Yangtze River in China, Diaz said, but the area has probably been hypoxic since the 1950s. “We just didn’t know about it,” he said.

Some of the reports are being published for the first time in journals accessible to Western scientists, he said.

Mississippi expert expected spread

Nancy Rabalais, executive director of the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, said she was not surprised at the increase in dead zones.

“There have been many more reported, but there truly are many more. What has happened in the industrialized nations with agribusiness as well that led to increased flux of nutrients from the land to the estuaries and the seas is now happening in developing countries,” said Rabalais, who was not part of Diaz’ research team.

She said she was told during a 1989 visit to South America that rivers there were too large to have the same problems as the Mississippi River, which this year was on track to create the second largest dead zone ever measured in the Gulf of Mexico. “Now many of their estuaries and coastal seas are suffering the same malady.”

“The increase is a troubling sign for estuarine and coastal waters, which are among some of the most productive waters on the globe,” she said.

From small to vast zones

Toepfer noted that 146 dead zones — most in Europe and the U.S. East Coast — range from under a square mile to up to 45,000 square miles. “Unless urgent action is taken to tackle the sources of the problem,” he said, “it is likely to escalate rapidly.”

The program noted that some of the earliest recorded dead zones were in Chesapeake Bay, the Baltic Sea, Scandinavia’s Kattegat Strait, the Black Sea and the northern Adriatic Sea.

The most infamous zone is in the Gulf of Mexico, where the Mississippi River dumps fertilizer runoff from the Midwest.

Others have appeared off South America, China, Japan, southeast Australia and New Zealand, the program said.

Preventive measures

The report was released in Jeju, South Korea, where governments from around the world are sending officials this week for a Global Ministerial Environment Forum.

The program noted preventive steps can be taken, citing these examples:

- European nations along the Rhine agreed to halve discharged nitrogen levels, reducing the discharge into the North Sea.

- Planting new forests and grasslands will help soak up excess nitrogen, keeping it out of waterways.

- Requiring vehicles to reduce nitrogen emissions.

- Fostering alternative energy sources that are not based on burning fossil fuels.

- Better sewage treatment would reduce nutrient discharges to coastal waters.

But the report also noted new research that indicates global warming could aggravate the problem. Should humans double emissions of carbon dioxide, a key gas that many scientists fear is warming the Earth, that could change rainfall patterns, according to the research.

“In some areas, this in turn could lead to a marked increase in the levels of run-off from rivers into the seas,” the U.N. program said. “They calculate that dissolved oxygen levels in the northern Gulf of Mexico, triggered by an increased discharge from the Mississippi River basin of 20 percent and a climb in temperature of up to four degrees Centigrade, could fall by 30 to 60 percent.”

The U.N. report is online at http://www.unep.org/yearbook/2009/.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.