Fact check: Is half a degree of warming really such a big deal?

When a human being’s temperature rises from a healthy 36.6 to 38.6 degrees Celsius (97.8 to 101.48 degrees Fahrenheit), it has consequences. Just a seemingly minor increase leaves the body feeling unwell and unable to function normally.

When a human being’s temperature rises from a healthy 36.6 to 38.6 degrees Celsius (97.8 to 101.48 degrees Fahrenheit), it has consequences. Just a seemingly minor increase leaves the body feeling unwell and unable to function normally.

It’s a similar story for the planet.

Since the late 19th century, when burning fossil fuels was becoming more widespread, the Earth has warmed by an average of more than 1 degree Celsius. Some places, however, have warmed beyond that level.

One of them is the Arctic. According to the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), a working group of the intergovernmental Arctic Council, the average annual temperature in the region jumped by3 degrees Celsius between 1971 to 2019. And that spells big problems for the region’s ecosystem.

Small temperature rise = big species losses

In a 2021 study published in The Cryosphere scientific journal, British researchers revealed findings indicating the loss of 28 trillion tons of ice between 1994 and 2017. They said the volume lost would be enough to cover the whole of the United Kingdom in an ice sheet 100 meters (328 feet) thick.

Using satellite data to examine glaciers and the poles, scientists from the UK’s University of Edinburgh, University College London and University of Leeds concluded that some 800 billion metric tons of ice was lost annually in the 1990s. By 2017, however, that number had risen to 1.2 trillion tons each year within that time span.

Steven Amstrup, chief scientist at United States-based conservation nongovernmental organization Polar Bears International, has been researching wildlife in the Arctic since the 1980s and has seen the changes firsthand.

“Back then, I remember looking at the sea ice that was right offshore in northern Alaska in the middle of summer — it was never very far from the coast,” he told DW.

“Now during the same period, the sea ice is hundreds of miles offshore. If you’d told me at the beginning of my career that I was going to see these kinds of changes, I would have said you’re crazy,” Amstrup said.

In findings published in the Nature Climate Journal last year, he and his colleagues predicted that if the temperature keeps rising, most polar bears, which prey on seals resting on the ice, could disappear by the end of the century.

“Sea ice is a polar bear’s dinner plate,” Amstrup said. “There’s almost nothing as nutritious as seals for them to eat on land.”

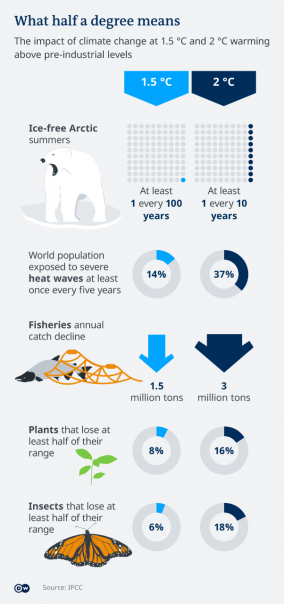

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts that if the planet warms 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the iconic polar species will still have sea ice during most Arctic summers. Under a 2 degrees scenario, however, they would face ice-free summers every 10 years.

Polar bears are not the only victims of rising temperature. Some 19% of species on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red list face an increased likelihood of extinction due to climate change.

At least one species has already been wiped out. In 2019, the Bramble Cay melomys, a tiny rodent that lived on a small sandy island at the tip of the Great Barrier Reef, became the first mammal to be officially recognized by the Australian government as extinct due to human-induced climate change. Rising sea levels and surging seas are believed to have wiped out its food and habitat.

Changes to our oceans are also impacting coral reefs, which serve as nurseries and pantries for up to a quarter of marine species. Warmer waters cause the corals to expel the sustaining marine algae from their tissues — known as bleaching. Prolonged bleaching kills the corals. A recent study found that Australia’s Great Barrier Reef has lost half its corals since 1995.

The IPCC has warned that if the planet warms beyond 2 degrees Celsius, corals will be almost entirely wiped out.

A world beyond 1.5 degrees Celsius

Small temperature increases will also change life for humans. People will be exposed to more extreme weather — heat waves, droughts, floods and tropical cyclones. Their frequency and severity will likely depend on how high temperatures rise.

If the world warms 2 degrees Celsius by 2100, the IPCC warns that 37% of the global population could be exposed to severe heat waves at least once every five years. Fewer than half of that number would be affected in a 1.5 degree scenario.

According to a 2018 study carried out by The Joint Research Center (JRC) of the European Commission’s science and knowledge service, as the world warms, two-thirds of the population will experience a progressive increase in drought conditions.

The UN Refugee Agency says increasing intensity of extreme weather events and sea-level rise are already causing more than 20 million people around the world each year to be internally displaced, or be forced to move to other parts of their country.

Displacement is an even bigger issue for small island nations in the Pacific, Indian Ocean and Caribbean.

“Countries like the Marshall Islands can carry adoption plans for a certain sea level rise,” said Helene Jacot Des Combes, a climate scientist at the University of the South Pacific, also an IPCC author and adaptation adviser to the Marshall Islands government.

“But if it continues to go up, then these islands won’t be inhabitable anymore.”

The Pacific island state of Fiji is also facing new realities. After being hit by 12 cyclones and other extreme weather events since 2016, the government launched a relocation program. More than 40 coastal communities need to be moved inland, and six of them have already been relocated.

Given the far-reaching consequences of just a slight temperature increase, the Paris climate accord ultimately aims to cap the global rise at 1.5 degrees Celsius in this century. But modeling suggests that based on current performance, the world is on track to reach that level of warming within the next 15 years.

And without radical action today, temperature increases won’t stop there. According to The Climate Action Tracker (CAT), an independent group of organizations that analyse governments’ climate action, even if all current promises and plans worldwide were met on time, temperatures would still rise to 2 to 2.2 degrees Celsius by the end of this century.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.