We Are Our Bacteria

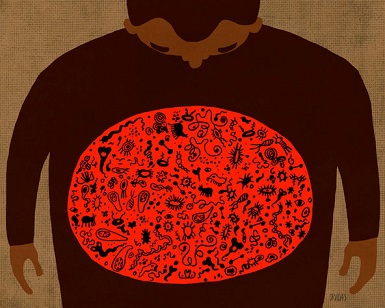

We may think of ourselves as just human, but we’re really a mass of microorganisms housed in a human shell. Every person alive is host to about 100 trillion bacterial cells. They outnumber human cells 10 to one and account for 99.9 percent of the unique genes in the body.

We may think of ourselves as just human, but we’re really a mass of microorganisms housed in a human shell. Every person alive is host to about 100 trillion bacterial cells. They outnumber human cells 10 to one and account for 99.9 percent of the unique genes in the body.Katrina Ray, a senior editor of Nature Reviews, recently suggested that the vast number of microbes in the gut could be considered a “human microbial ‘organ’” and asked, “Are we more microbe than man?”

Our collection of microbiota, known as the microbiome, is the human equivalent of an environmental ecosystem. Although the bacteria together weigh a mere three pounds, their composition determines much about how the body functions and, alas, sometimes malfunctions.

Like ecosystems the world over, the human microbiome is losing its diversity, to the potential detriment of the health of those it inhabits.

Dr. Martin J. Blaser, a specialist in infectious diseases at the New York University School of Medicine and the director of the Human Microbiome Program, has studied the role of bacteria in disease for more than three decades. His research extends well beyond infectious diseases to autoimmune conditions and other ailments that have been increasing sharply worldwide.

In his new book, “Missing Microbes,” Dr. Blaser links the declining variety within the microbiome to our increased susceptibility to serious, often chronic conditions, from allergies and celiac disease to Type 1 diabetes and obesity. He and others primarily blame antibiotics for the connection.

The damaging effect of antibiotics on microbial diversity starts early, Dr. Blaser said. The average American child is given nearly three courses of antibiotics in the first two years of life, and eight more during the next eight years. Even a short course of antibiotics like the widely prescribed Z-pack (azithromycin, taken for five days), can result in long-term shifts in the body’s microbial environment.

But antibiotics are not the only way the balance within us can be disrupted. Cesarean deliveries, which have soared in recent decades, encourage the growth of microbes from the mother’s skin, instead of from the birth canal, in the baby’s gut, Dr. Blaser said in an interview.

This change in microbiota can reshape an infant’s metabolism and immune system. A recent review of 15 studies involving 163,796 births found that, compared with babies delivered vaginally, those born by cesarean section were 26 percent more likely to be overweight and 22 percent more likely to be obese as adults.

The placenta has a microbiome of its own, researchers have discovered, which may also contribute to the infant’s gut health and help mitigate the microbial losses caused by cesarean sections.

Other studies have found major differences in the microorganisms living in the guts of normal-weight and obese individuals. Although such studies cannot tell which came first — the weight problem or the changed microbiota — studies indicate obese mice have gut bacteria that are better able to extract calories from food.

Further evidence of a link to obesity comes from farm animals. About three-fourths of the antibiotics sold in the United States are used in livestock. These antibiotics change the animals’ microbiota, hastening their growth.

When mice are given the same antibiotics used on livestock, the metabolism of their liver changes, stimulating an increase in body fat, Dr. Blaser said.

Even more serious is the increasing number of serious disorders now linked to a distortion in the microbial balance in the human gut. They include several that are becoming more common in developed countries: gastrointestinal ailments like Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and celiac disease; cardiovascular disease; nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; digestive disorders like chronic reflux; autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis; and asthma and allergies.

Some researchers have even speculated that disruptions of gut microbiota play a role in celiac disease and the resulting explosion in demand for gluten-free foods even among people without this disease. In a mouse model of Type 1 diabetes, treating the animals with antibiotics accelerates the development of the disease, Dr. Blaser said.

He and other researchers, including a team from Switzerland and Germany, have also linked the serious rise in asthma rates to the “rapid disappearance of Helicobacter pylori, a bacterial pathogen that persistently colonizes the human stomach, from Western societies.” Once, virtually everyone harbored this microbe, which European researchers have shown protected mice from developing hallmarks of allergic asthma.

H. pylori colonization in early life encourages production of regulatory T-cells in the blood, which Dr. Blaser said are needed to tamp down allergic responses. Although certain strains of H. pylori are linked to the development of peptic ulcer and stomach cancer, other strains are protective, his studies indicate.

Research by Dr. Blaser and his colleagues further suggests that H. pylori in the stomach protects against gastroesophageal reflux disease, Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer.

Still, it is not always possible for researchers to tell whether disruptions in gut microbiota occur before or after people become ill. However, studies in laboratory animals often suggest the bacterial disturbances come first.

Dr. Blaser, among many others, cautions against the overuse of antibiotics, especially the broad-spectrum drugs now commonly prescribed. He emphasized in particular the importance of using fewer antibiotics in children.

“In Sweden, antibiotic use is 40 percent of ours at any age, with no increase in disease,” he said. “We need to educate physicians and parents that antibiotics have costs. We need improved diagnostics. Is the infection caused by a virus or bacteria, and if bacteria, which one?

“Then we need narrow-spectrum antibiotics designed to knock out the pathogenic bacteria without disrupting the health-promoting ones,” Dr. Blaser added. “This will make it possible to treat serious infections with less collateral effect.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.