Warming winter sends no love to Olympic bid cities

All five cities vying to host the 2022 winter games could face some of the warmest weather they’ve ever seen when the Olympics open, according to a Daily Climate analysis.

With athletes at the Sochi games complaining about mushy snow, a peek at what climate models are predicting might be prudent when picking host cities in the future.

The temperature has settled into the mid-50s this week at the Sochi Olympics, and snowboarders were furious at the slushy condition of the halfpipe Tuesday. Four years ago at the Vancouver Olympics, rain and fog delayed downhill skiing events, and organizers resorted to straw bales to build jumps and obstacles for courses where snow proved scarce.

None of this bodes well for future Olympics.

A warming climate may rule out warmer venues such as Sochi or Vancouver in the future. But five cities vying to host the 2022 Winter Olympics also could be confounding athletes with unusually warm weather eight years from now.

Upper limits of experience

All of the candidate cities – Almaty, Kazakhstan; Beijing, China; Krakow, Poland; Lviv, Ukraine; and Oslo, Norway – will likely be facing temperatures near the upper limits of what each region has experienced in the past 150 years, according to a Daily Climate analysis of climate models constructed by University of Hawaii, Manoa, geographer Camilo Mora and colleagues.

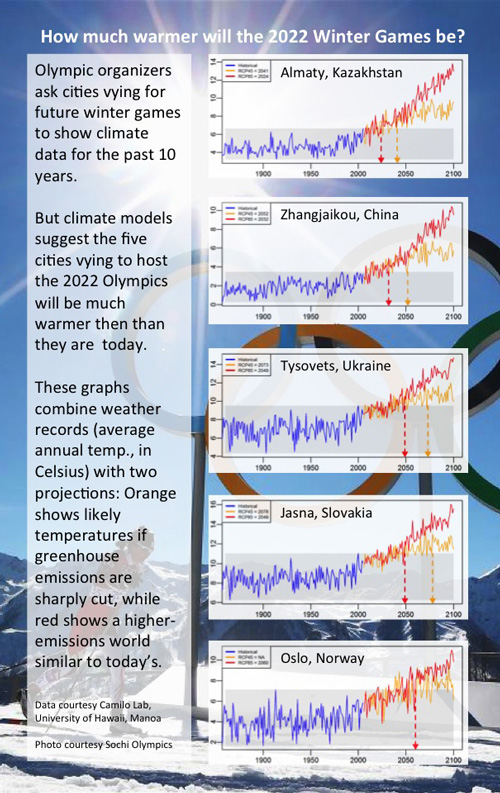

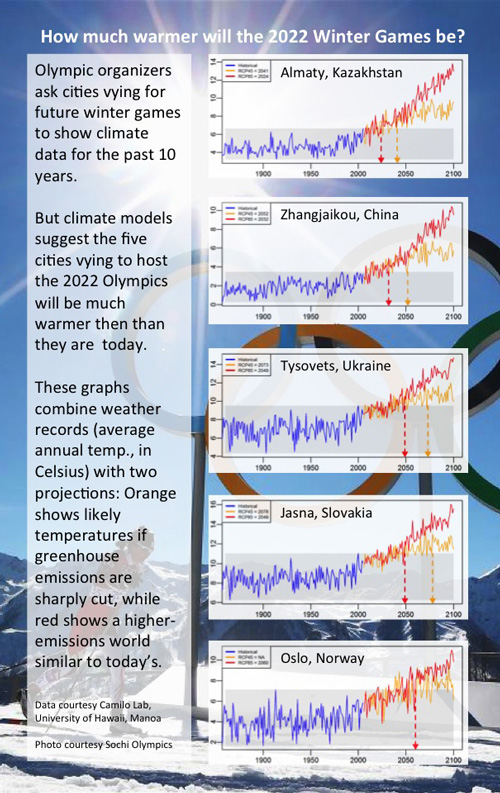

Mora’s models merge temperature records with climate forecasts to predict when the temperature for any given region “departs” from its historic range.

But it’s also possible, using the models, to show where the temperatures might be in the 2020s. All five cities being considered by the International Olympic Committee for the 2022 games will likely be in the upper half of the hottest weather records they’ve seen over the past century and a half.

The data suggest that high altitudes and northern latitudes may be an increasingly important factor in siting future Olympic venues.

The data suggest that high altitudes and northern latitudes may be an increasingly important factor in siting future Olympic venues.

“Winters are going to get shorter. There will be fewer days below freezing. In fact, that is already happening,” said Mora.

The International Olympic Committee declined to speculate on how climate projections might affect siting decisions for future winter games.

Weather data are collected during the bidding process, IOC spokeswoman Sandrine Tonge said in an email, and assessed by a commission that provides a “detailed report” to IOC members before the vote.

The host city for the 2022 Winter Olympics will be announced in 2015.

The IOC first mentioned climate change in its official report of the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano.

Looking to the future

The five cities, some of which plan to hold snow events as far as 130 miles away, must complete a 250-page questionnaire, which includes a section on climate and weather conditions. Cities are asked to list average high and low temperatures as well as precipitation for the month of February at each venue.

But the questionnaire, which asks for averages based on weather conditions over the past 10 years, does not require cities to anticipate how climate may change in the seven to eight years between bidding and hosting the games.

Mora’s models do show only average annual temperature – collapsing seasonal extremes into one number for the year. They do not show how soon or to what extent winter conditions in the bid cities could become unsuitable for hosting the games. And while computer models have become much more sophisticated, they still have difficulty predicting future temperatures for precise regions.

“The models show nothing about projected winter change. Usually the winter season change in the Northern Hemisphere is more pronounced,” said Daniel Scott, professor of tourism management at the University of Waterloo in Canada.

But the data do put the warming trend into vivid relief. And they suggest that a look back at the past 10 years’ of climate data would offer little bearing on what Olympic athletes would face come 2022.

Completely different as soon as 2024

Almaty, in central Asia, for instance, may have a completely different climate as soon as 2024 if global greenhouse gas emissions continue under a “business-as-usual” scenario, based on Mora’s data.

Beijing and its co-host to the north – Zhangjaikou – where the snow events would be held aren’t much far behind. Mora’s models suggest Zhangjaikou could leave its historical climate behind as early as 2032.

The mountain towns of Tysovets, Ukraine and Jasna, Slovakia, where Lviv and Krakow propose hosting alpine events, would begin to look more like Black Sea resorts such as Odessa, Constanta or Sochi by the 2050s, based on data from Charles Koven, a climate scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

The most northern city in the running for the 2022 Olympics, Oslo, can expect to stay within its climate norms the longest – to 2060 or beyond.

“High latitude places often have late climate departures, but that does not necessarily mean climate change won’t impact those places,” Mora said.

While Mora’s models, based on yearly average temperatures, don’t forecast monthly highs, lows or precipitation changes, they do show warming trends.

“Gone for good’

The “departure point,” Mora cautioned, signifies “the year after which the climate we knew is gone for good.”

In a report published last month, Scott found that average February temperatures for the 19 previous Winter Olympic host cities could be expected to rise between 3.4 and 3.8 degrees Fahrenheit by 2050, and up to 8 degrees Fahrenheit by 2090, leaving only six previous host cities cold enough to host the Games 75 years from now.

Places such as Squaw Valley, Vancouver and Sochi would no longer have cold enough winters to host again, while cities like Lake Placid or Nagano, Japan, would be iffy.

Sochi, the subtropical Black Sea resort town, boasts February daytime highs around 50 and lows in the mid 30s, putting it climactically on par with Richmond, Va. Snow events such as alpine skiing and snowboarding are being held at the Rosa Khutor resort, a 50-mile drive from Sochi in the Caucasus Mountains.

Snowmaking has made warmer venues possible in recent years, according to Scott’s report.

At Sochi, organizers have enlisted three $2 million snowmaking units capable of creating snow at temperatures up to 70 degrees Fahrenheit to ensure good track coverage at the Nordic combined and ski jump events.

But there are limits to snowmaking as an adaptation for climate change, said Scott. “Can you make enough snow and not have it melt? If that is doable physically, then it is an economics question.”

Added Mora: “It will be interesting to see how cities around the world who rely on winter sports will be forced to invest as a result of climate change.”

With athletes at the Sochi games complaining about mushy snow, a peek at what climate models are predicting might be prudent when picking host cities in the future.

The temperature has settled into the mid-50s this week at the Sochi Olympics, and snowboarders were furious at the slushy condition of the halfpipe Tuesday. Four years ago at the Vancouver Olympics, rain and fog delayed downhill skiing events, and organizers resorted to straw bales to build jumps and obstacles for courses where snow proved scarce.

None of this bodes well for future Olympics.

A warming climate may rule out warmer venues such as Sochi or Vancouver in the future. But five cities vying to host the 2022 Winter Olympics also could be confounding athletes with unusually warm weather eight years from now.

Upper limits of experience

All of the candidate cities – Almaty, Kazakhstan; Beijing, China; Krakow, Poland; Lviv, Ukraine; and Oslo, Norway – will likely be facing temperatures near the upper limits of what each region has experienced in the past 150 years, according to a Daily Climate analysis of climate models constructed by University of Hawaii, Manoa, geographer Camilo Mora and colleagues.

Mora’s models merge temperature records with climate forecasts to predict when the temperature for any given region “departs” from its historic range.

But it’s also possible, using the models, to show where the temperatures might be in the 2020s. All five cities being considered by the International Olympic Committee for the 2022 games will likely be in the upper half of the hottest weather records they’ve seen over the past century and a half.

The data suggest that high altitudes and northern latitudes may be an increasingly important factor in siting future Olympic venues.

The data suggest that high altitudes and northern latitudes may be an increasingly important factor in siting future Olympic venues.“Winters are going to get shorter. There will be fewer days below freezing. In fact, that is already happening,” said Mora.

The International Olympic Committee declined to speculate on how climate projections might affect siting decisions for future winter games.

Weather data are collected during the bidding process, IOC spokeswoman Sandrine Tonge said in an email, and assessed by a commission that provides a “detailed report” to IOC members before the vote.

The host city for the 2022 Winter Olympics will be announced in 2015.

The IOC first mentioned climate change in its official report of the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano.

Looking to the future

The five cities, some of which plan to hold snow events as far as 130 miles away, must complete a 250-page questionnaire, which includes a section on climate and weather conditions. Cities are asked to list average high and low temperatures as well as precipitation for the month of February at each venue.

But the questionnaire, which asks for averages based on weather conditions over the past 10 years, does not require cities to anticipate how climate may change in the seven to eight years between bidding and hosting the games.

Mora’s models do show only average annual temperature – collapsing seasonal extremes into one number for the year. They do not show how soon or to what extent winter conditions in the bid cities could become unsuitable for hosting the games. And while computer models have become much more sophisticated, they still have difficulty predicting future temperatures for precise regions.

“The models show nothing about projected winter change. Usually the winter season change in the Northern Hemisphere is more pronounced,” said Daniel Scott, professor of tourism management at the University of Waterloo in Canada.

But the data do put the warming trend into vivid relief. And they suggest that a look back at the past 10 years’ of climate data would offer little bearing on what Olympic athletes would face come 2022.

Completely different as soon as 2024

Almaty, in central Asia, for instance, may have a completely different climate as soon as 2024 if global greenhouse gas emissions continue under a “business-as-usual” scenario, based on Mora’s data.

Beijing and its co-host to the north – Zhangjaikou – where the snow events would be held aren’t much far behind. Mora’s models suggest Zhangjaikou could leave its historical climate behind as early as 2032.

The mountain towns of Tysovets, Ukraine and Jasna, Slovakia, where Lviv and Krakow propose hosting alpine events, would begin to look more like Black Sea resorts such as Odessa, Constanta or Sochi by the 2050s, based on data from Charles Koven, a climate scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

The most northern city in the running for the 2022 Olympics, Oslo, can expect to stay within its climate norms the longest – to 2060 or beyond.

“High latitude places often have late climate departures, but that does not necessarily mean climate change won’t impact those places,” Mora said.

While Mora’s models, based on yearly average temperatures, don’t forecast monthly highs, lows or precipitation changes, they do show warming trends.

“Gone for good’

The “departure point,” Mora cautioned, signifies “the year after which the climate we knew is gone for good.”

In a report published last month, Scott found that average February temperatures for the 19 previous Winter Olympic host cities could be expected to rise between 3.4 and 3.8 degrees Fahrenheit by 2050, and up to 8 degrees Fahrenheit by 2090, leaving only six previous host cities cold enough to host the Games 75 years from now.

Places such as Squaw Valley, Vancouver and Sochi would no longer have cold enough winters to host again, while cities like Lake Placid or Nagano, Japan, would be iffy.

Sochi, the subtropical Black Sea resort town, boasts February daytime highs around 50 and lows in the mid 30s, putting it climactically on par with Richmond, Va. Snow events such as alpine skiing and snowboarding are being held at the Rosa Khutor resort, a 50-mile drive from Sochi in the Caucasus Mountains.

Snowmaking has made warmer venues possible in recent years, according to Scott’s report.

At Sochi, organizers have enlisted three $2 million snowmaking units capable of creating snow at temperatures up to 70 degrees Fahrenheit to ensure good track coverage at the Nordic combined and ski jump events.

But there are limits to snowmaking as an adaptation for climate change, said Scott. “Can you make enough snow and not have it melt? If that is doable physically, then it is an economics question.”

Added Mora: “It will be interesting to see how cities around the world who rely on winter sports will be forced to invest as a result of climate change.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.