US efforts to curb threat from livestock waste bog down.

As factory farms take over more and more of the nation’s livestock production, a major environmental threat has emerged: Pollution from the waste produced by the immense crush of animals.

As factory farms take over more and more of the nation’s livestock production, a major environmental threat has emerged: Pollution from the waste produced by the immense crush of animals.The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that America’s livestock create three times as much excreta as the human population. By the agency’s reckoning, a dairy farm with 2,500 cows – which is large, but not exceptional – can generate as much waste as the people in a city the size of Miami.

Yet unlike human waste, which often receives sophisticated treatment, animal waste commonly goes untreated. It is typically held in underground pits or vast manure lagoons, and then spread on cropland as fertilizer. It’s been this way for decades, but worries have grown along with the number and size of factory farms. When storms strike, the overflows can be huge, like the 1995 North Carolina swine manure spill that sent 25 million gallons of waste into a river.

Just last month, a Minnesota dairy farm spilled up to 1 million gallons of manure, fouling two nearby trout streams. More routinely, as the U.S. Department of Agriculture has said, large farms generate more manure than they can handle, so they spread too much on nearby fields. From there, the material – which the EPA says often contains hormones, pathogens and toxic metals – can run off and contaminate streams, rivers and wells.

Under the Clean Water Act, industrial operations like factories and sewage treatment plants that discharge through pipes are considered “point sources” of pollution. They are required to get a permit that sets limits on pollution and, in many cases, imposes a water testing regime.

For massive livestock farms – what the government calls concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs – it’s a different story. Although they also are defined under the law as point sources, federal court rulings have frustrated the EPA’s efforts to regulate them. Only 45 percent of the nation’s CAFOs have discharge permits, even though the EPA estimates 75 percent are actually polluting. And even when CAFOs get permits, critics say, their performance in controlling pollution is hard to track and their permit restrictions are tough to enforce.

EPA officials, who declined to be interviewed for this story, have worried for many years about pollution problems from CAFOs and say they have stepped up enforcement in recent years. But the agency’s plans to regulate more large livestock farms were shot down twice by federal courts over the last decade. Then last July – amid continuing industry opposition and while regulation was a sensitive topic in the presidential campaign – the agency quietly withdrew a proposal to collect information from large livestock farms. The result is that the EPA remains largely in the dark about such basic facts as which operations are potentially the biggest polluters and where they are located.

“It’s basically the Wild West out there when it comes to CAFOs,” said Scott Edwards, an attorney for the advocacy group Food and Water Watch.

But industry groups say those who call for tighter regulation rely on outdated data and ignore evidence of the progress the industry has made through improved technology and farming practices.

Michael Formica, chief environmental counsel for the National Pork Producers Council, says most of the waste in newer swine farms goes into deep pits that aren’t vulnerable to overflow the way manure lagoons are. He added that few farms endanger waterways by applying too much manure on fields. “The value of the nutrients in the manure is worth way too much for people not to want to harness it and utilize it,” he said.

Jamie Jonker, vice president of scientific and regulatory affairs for the National Milk Producers Federation, said, “Dairy farms of all sizes strive to be as environmentally friendly as possible.”

The Nose-Burning Smell

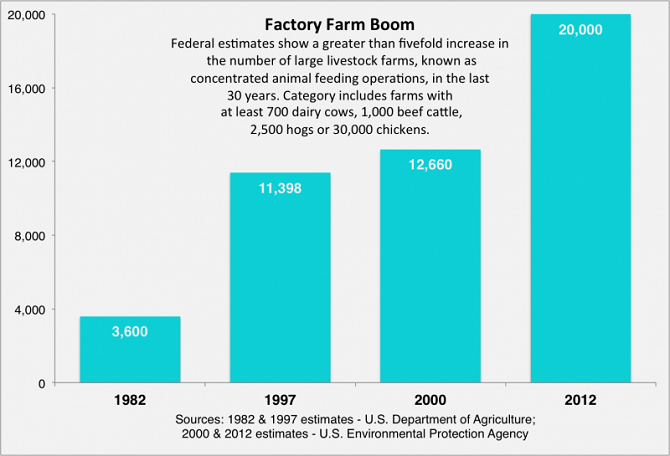

Federal estimates vary, but the EPA believes there now are 20,000 large U.S. farms that qualify as CAFOs. That would be up more than fivefold since 1982, when agriculture officials concluded that 3,600 farms were big enough to meet the federal definition of a CAFO. The EPA’s definition of large CAFOs includes livestock operations that confine at least 700 dairy cows, 2,500 pigs weighing over 55 pounds, 125,000 meat chickens, 30,000 laying hens or 1,000 beef cows.

Meanwhile, the EPA says, at least 29 states cite animal agriculture as a contributor to water quality problems. In February, the agency released a report that found 55 percent of U.S. streams and rivers were in “poor condition for aquatic life” and cited pollution from livestock and crop farms as a leading factor. Agricultural runoff is partly to blame for a so-called dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico that was the size of New Jersey in 2011, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

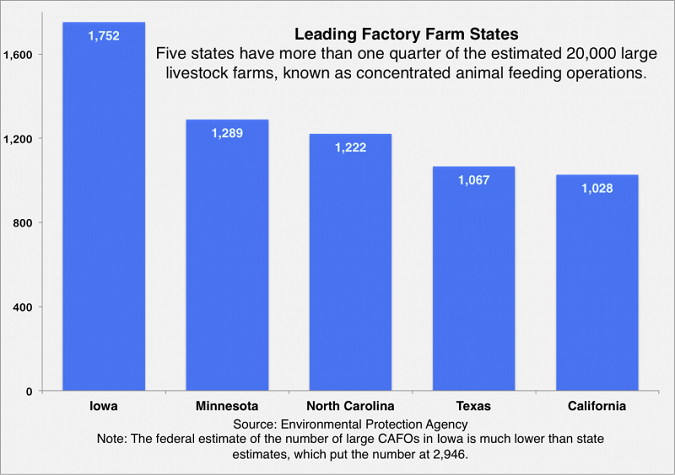

For people who live near big livestock farms, like Lori Nelson, there’s also the problem of stench. She grew up on a farm and still keeps some animals on her land in Bayard, Iowa, two rural acres that, when she bought it, were peaceful, surrounded by soy fields. But seven years ago, she got some unwelcome neighbors – two large hog farms housing a total of 5,000 animals. That many hogs produce as much waste as 15,000 people and, on bad days, the nose-burning smell is enough to send Nelson and her husband running from their cars to the house. It was also enough to convert Nelson into an unlikely activist. She is working to halt the spread of industrial livestock farms in Iowa, the nation’s top producer of pork and eggs and home to more large livestock farms than any other state.

Nelson no longer drinks from her well for fear of contamination. She says manure from the swine farms is often spread right to the edge of a tributary to the Raccoon River – a river whose levels of potentially harmful nitrates, which are found in fertilizers and manure runoff, hit record levels this month. Nelson figures that she has no hope of selling her own place. Its value tanked when the hogs moved in and now she says she couldn’t even get what she owes on the property. Even if she could move to another rural area, there’s no guarantee a CAFO wouldn’t move in next door. “There’s no place to go. It seems like anywhere you go, you’re eventually going to be surrounded by a factory farm,” she said.

Many environmentalists say, and federal reviews have found, that some state authorities in charge of enforcing the Clean Water Act are doing a poor job, and that the EPA’s oversight of these programs has fallen short. At the same time, industry groups and their lawmaker allies in a handful of states are pushing to insulate the livestock industry from scrutiny from citizens, environmental and animal welfare groups and regulators. Some are trying to enshrine “Right to Farm” provisions in state constitutions, even though similar laws are already on the books in every state. In other cases they are trying to criminalize activists’ undercover investigations at livestock farms.

“The industry obviously has a lot of money and [is] very important to the American economy and American people. Trying to regulate farms is a politically dangerous thing to do in the U.S.” said Kathy Hessler, a professor at Lewis & Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon.

Catch Me if You Can

The EPA’s concerns about CAFOs go back at least to 1988, when the Clinton administration, in a document called the Clean Water Action Plan, concluded that pollution from factories and treatment plants had been dramatically reduced. But it said that pollution from farms, including livestock operations, remained a serious problem.

Still, it wasn’t until 2003 when the EPA, responding to a lawsuit from environmental groups, issued a new rule intended to require all large livestock farms to get Clean Water Act permits unless they could demonstrate that they had no potential to pollute. This blanket requirement would have vastly expanded the number of operations with permits. The agency justified the move by saying there were many documented instances of pollution from CAFOs lacking federal permits and that these farms might escape detection because they — unlike more easily monitored polluters, such as factories or water treatment plants — discharge only intermittently (during rain, for example).

That plan, however, was quickly contested in court. Industry groups argued the agency could require permits only for factory farms that were actually discharging into waterways — meaning those that acknowledge polluting or have been found by inspectors to pollute. The EPA’s authority, they argued, did not extend to potential polluters. In 2005, a federal judge ruled in the industry’s favor.

EPA came back in 2008 with a dialed-back rule. This time around, the agency would not require all CAFOs to get permits, only those confirmed to be discharging into waterways or those that, as the agency put it, “proposed to discharge.” The second category were CAFOs that, the EPA said, were “designed, constructed, operated, or maintained such that a discharge would occur” — in other words, ones that inevitably would pollute. Once again, industry groups filed suit, arguing, as they did in the challenge to the 2003 rule, that the EPA could require permits only of “actual discharges.” A federal court agreed, vacating in 2011 the section of the rule dealing with the second category of CAFOs.

The rulings, environmentalists say, left the EPA in what some called a “catch me if you can” situation—able to do little without proving, after the fact, that a farm has polluted.

A Bitter Defeat

Then the EPA, prodded by a lawsuit from environmental groups, unveiled a comparatively modest plan to learn more about the scope of the problem. It proposed collecting basic information about large livestock farms, a potential starting point for stepped up oversight. The move was intended to address a key weakness in the EPA’s ability to regulate large livestock farms — there is no national database showing where these farms are located, who owns them and whether they are polluting. A report critical of the agency in 2008 from the Government Accountability Office called the limited data the EPA has “inconsistent and inaccurate.”

Initially, the EPA agreed to ask owners or operators of large CAFOs to submit 14 pieces of information, including names, addresses and geographic coordinates.

But by the time the agency released the proposal for comment in October 2011, it was reduced to two watered down options–one to require less information, and the other to require reporting only by farmers in certain watersheds.

Talking points prepared by the EPA for a meeting between officials of the agency and the U.S. Department of Agriculture – a document obtained by FairWarning through a Freedom of Information Act request – indicated that the changes followed “concerns raised both by industry and USDA.”

The Office of Management and Budget, a White House agency that reviews proposed regulations, also played a role. For example, documents show that the OMB suggested that the EPA change some requirements, such as allowing an “authorized representative” of a farm to provide his or her name instead of a CAFO owner to protect the operation’s privacy.

Even so, the meat industry and its Congressional allies objected. One of their main arguments was that collecting and making the information publicly available would pose a security threat to farmers and the U.S. food supply. A letter signed by dozens of industry groups and sent to OMB cited allegedly illegal acts by animal rights groups, including incidents in which hens and turkeys were set free.

It is “absolutely incomprehensible that, while other parts of the federal government are trying to protect the security of our food supply, OMB would even consider allowing EPA to undermine these efforts by making public the locations of animal production facilities,” the letter read.

On July 13 – less than four months before the presidential election and while the Obama administration was being hammered as too zealous about regulation — the EPA quietly withdrew the proposal.

For environmental groups, it was a bitter defeat. The “information-gathering rule was supposed to lift the veil on CAFOs,” said Edwards, of Food and Water Watch. “Instead the EPA just got up and walked away.”

In his first presidential campaign, Obama’s tough talk about factory farms won him supporters in the Midwest. He promised, in a white paper, to strictly regulate large livestock farms, which he said “pollute the environment” and “jeopardize public health.”

The administrations’ inaction on large livestock farms was seen as a politically motivated betrayal by environmental groups. It also was the latest disappointment for those who expected to see reforms in the agriculture industry. Just weeks before withdrawal of the CAFO rule, for example, the Department of Labor scrapped a proposal that would have strengthened safety measures for children doing dangerous work on farms. In 2011, the Obama administration backed down on a promise to break up big meat monopolies.

Rena Steinzor, a University of Maryland law professor and president of the Center for Progressive Reform, is among those who believe the EPA was likely pressured by the White House to withdraw the rule: “You don’t just write a rule and then say, ‘Oops, we made a mistake,’” she said. The White House did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

In place of the rule, the EPA settled for collecting data from existing sources—a solution the agency earlier said wouldn’t work. An EPA-commissioned assessment of state and federal resources available online showed large gaps in the available data.

But industry groups applauded the EPA’s retreat. Formica of the Pork Producers said the rule would have simply burdened farmers with pointless paperwork. “You want your farmers focused on farming and running the farm, you don’t want them worried about filling out one inane form after another,” he said.

They also expressed satisfaction that it would be more difficult for the EPA to get information without a law compelling disclosure. Ashley McDonald, deputy environmental counsel for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association said that his organization was pleased the effort would be more “labor intensive” because the data is “in a decentralized form that is much more difficult to ascertain.”

Among the places the EPA won’t be getting the information is the USDA, even though the agency collects much of it. During closed-door negotiations, an amendment to the 2008 Farm Bill was added that makes information submitted to the agency for subsidy and grant applications off-limits to the public and other federal agencies, in most cases.

Even though the proposed rule was withdrawn nine months ago, people are still fighting over it. The environmental groups that were party to the original settlement, including Earthjustice and the Natural Resources Defense Council, are weighing whether to sue the EPA. To help determine if they have a case, they filed a Freedom of Information Act request for correspondence between the agency and outside groups and information it collected during the decision-making process.

They got back information collected from 29 states with names, addresses and other information about some producers. Much of the information, the agency has said, is publicly available on the Internet and was not disseminated by the environmental groups. Still, meat industry groups were furious. One feedlot owner said: “The only thing it doesn’t do is chauffeur these extremists to my house.”

But many reject the argument that disclosing the location of CAFOs poses a major security threat, arguing that information about far more critical sites — such as power plants and hospitals — is freely available. “And we’re worried about a chicken farm?” said Edwards.

In April, Republican senators sent EPA’s acting administrator a letter demanding answers about the information release. Forty House members – all but two of them Republicans — sent a similar letter. The lawmakers urged the agency to abandon any effort to assemble a public database and instead “refocus your efforts to ensure that the recent release of data is not misused in a way that threatens our Nation’s producers and the integrity of the food supply.”

This month, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association asked the Environmental Protection Agency’s Inspector General to investigate.

Chilling Effect

In the absence of strong federal or state oversight, citizen groups have tried to play a role, said Patrick Parenteau, a professor at Vermont Law School, but their success has been mixed. For instance, Nelson’s activist group, Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement, says it blocked the construction of 14 factory farms last year. On the other hand, an effort led by the Waterkeeper Alliance to crack down on alleged pollution by a chicken farm in Maryland backfired badly. Not only was their suit against the farm and poultry giant Perdue Farms dismissed, but now the erstwhile defendants are asking the judge to order the environmental groups to pay $3 million in legal fees.

Parenteau says the threat of legal fees could have a chilling effect, “It says to these groups: The price you may pay for bringing a suit that you lose may be your ruin.”

That seems to be exactly what Perdue – the nation’s third-largest chicken producer – is going for. “Simply put, awarding litigation fees is the most effective way to discourage the Waterkeeper Alliance from doing more of the same,” a lawyer for Perdue said in a statement in February

For the most part, the EPA delegates authority to enforce the Clean Water Act to states. But the states’ willingness and ability to enforce the law can vary widely, and activists in some states have accused EPA of poor oversight. In Iowa, for example, environmental groups in 2007 first asked the EPA to revoke the state’s authority to enforce the Clean Water Act. After four years of what they considered insufficient action by EPA, they gave notice of intent to sue the agency. Only then did the EPA investigate the state’s regulation of CAFOs, leading to a scathing report that echoed many of the complaints environmental groups have made for years.

The agency’s oversight of other states has also been criticized. In 2011, for example, the EPA’sinspector general found “significant deficiencies” in the agency’s oversight of Georgia’s CAFO program.

Meanwhile, agribusiness and sympathetic lawmakers are trying to shield the industry from scrutiny from regulators and environmental groups. Over the last two years a dozen states have considered, and three states have passed, so-called “Ag-gag” bills. They would make it illegal for activists to shoot undercover video in livestock farms or apply for a job under false pretenses.

In addition, there is a push to beef up the “Right to Farm laws” in some of the 50 states that already have such legislation on the books. While varying from state-to-state, these provisions largely originated in the 1980s as a way to defend farmland against encroaching development and new neighbors who might object to the sounds and smells of agriculture. Lately there has been an effort to insert in state constitutions a right to farm — a right not spelled out for other occupations. North Dakota in November became the first state to amend its constitution to permanently guarantee the right to use “modern farming and ranching practices” – a term critics say is overly broad and could preclude stronger animal welfare and environmental rules.

Other states, like Wisconsin, have amended their Right to Farm laws to pre-empt local communities’ ability to impose tougher rules on factory farms. The state is seeing a fast increase in the number of industrial dairies – in 1990, there were just two dairy CAFOs. Today, there are 216, according to the state’s Department of Natural Resources, and Gov. Scott Walker is pushing for more expansion.

Some towns are finding the law may leave them with few options when a large farm wants to expand or move in. The township of Lincoln, for instance, is already surrounded by industrial dairies. And its water is polluted — 38 percent of the wells had coliform bacteria levels, and 24 percent had nitrate levels, that exceeded health standards, according to an analysis by the University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point. Both contaminants can be caused by manure, though there are other possible sources, such as leaking septic tanks.

Now one dairy, Kinnard Farms, plans to increase its herd from about 5,800 to 8,700 cows, a document from the state of Wisconsin shows. To do so, it will build three manure storage tanks that will hold a combined 76 million gallons of manure — as much as 120 Olympic-sized swimming pools. The tanks would sit 1,000 feet from the house where Dan and Ericka Routhieaux and their three kids live. A pond to collect runoff from the farm would be even closer – about 50 feet from their front yard and 260 feet from their well. Three other nearby families have already moved and the Routhieauxs recently abandoned their plans to stay and fight and are now trying to sell their land to the dairy.

They don’t want to go. Ericka grew up in the town and the couple is raising three kids on 15 mostly wooded acres they bought two decades ago. But once the dairy expands, the Routhieauxs fear that their property values will drop and that the family may be exposed to hydrogen sulfide and ammonia or have their well contaminated with nitrates and bacteria. “Our health is our main concern. I just don’t know how we’re going to be able to live here,” Ericka Routhieaux said.

All told, critics such as Parenteau wonder if there ever will be a way to bring CAFO pollution under control. The sheer scale of industrial livestock production might be unmanageable by definition, he said. “It’s a bigger, cultural and economic question: Can we really afford the damage that these massive agricultural operations are doing?” But he acknowledges there’s no real forum for that conversation: “Congress certainly isn’t interested in having that discussion, so there we are,” he said. “We’re kind of stuck.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.