U.S. Is Playing Catch-Up With Russia in Scramble for the Arctic

With warming seas creating new opportunities at the top of the world, nations are scrambling over the Arctic — its territorial waters, transit routes and especially its natural resources — in a rivalry some already call a new Cold War.

When President Obama travels to Alaska on Monday, becoming the first president to venture above the Arctic Circle while in office, he hopes to focus attention on the effects of climate change on the Arctic. Some lawmakers in Congress, analysts, and even some government officials say the United States is lagging behind other nations, chief among them Russia, in preparing for the new environmental, economic and geopolitical realities facing the region.

“We have been for some time clamoring about our nation’s lack of capacity to sustain any meaningful presence in the Arctic,” said Adm. Paul F. Zukunft, the Coast Guard’s commandant.

Aboard the Alex Haley, the increased activity in the Arctic was obvious in the deep blue waters of the Chukchi Sea. While the cutter patrolled one day this month, vessels began to appear one after another on radar as this ship cleared the western edge of Alaska and cruised north of the Arctic Circle.

There were three tugs hauling giant barges to ExxonMobil’s onshore natural gas project east of Prudhoe Bay. To the east, a flotilla of ships and rigs lingered at the spot where Royal Dutch Shell began drilling for oil this month. Not far away, across America’s maritime border, convoys of container ships and military vessels were traversing the route that Russia dreams of turning into a new Suez Canal.

The cutter, a former Navy salvage vessel built nearly five decades ago, has amounted to the government’s only asset anywhere nearby to respond to an accident, oil spill or incursion into America’s territory or exclusive economic zone in the Arctic.

To deal with the growing numbers of vessels sluicing north through the Bering Strait, the Coast Guard has had to divert ships like the Alex Haley from other core missions, like policing American fisheries and interdicting drugs. The service’s fleet is aging, especially the nation’s only two icebreakers. (The United States Navy rarely operates in the Arctic.) Underwater charting is paltry, while telecommunications remain sparse above the highest latitudes. Alaska’s far north lacks deepwater port facilities to support increased maritime activity.

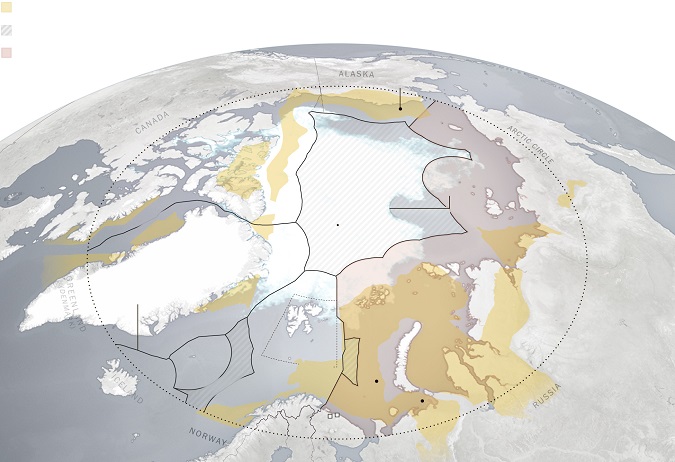

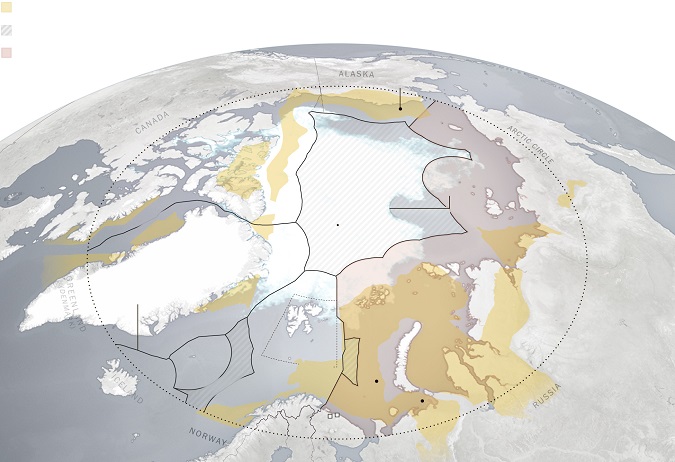

The Competition for Resources in the Arctic

Areas with 50% or greater chance of large undiscovered oil and gas reserves

High seas and outer continental shelf

Extent of Arctic waters under Russian control

All these shortcomings require investments that political gridlock, budget constraints and bureaucracy have held up for years.

Russia, by contrast, is building 10 new search-and-rescue stations, strung like a necklace of pearls at ports along half of the Arctic shoreline. More provocatively, it has also significantly increased its military presence, reopening bases abandoned after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Russia is far from the only rival — or potential one — in the Arctic. China, South Korea and Singapore have increasingly explored the possibility that commercial cargo could be shipped to European markets across waters — outside Russia’s control — that scientists predict could, by 2030, be ice-free for much of the summer.

In 2012, with great fanfare, China sent a refurbished icebreaker, the Xuelong, or Snow Dragon, across one such route. Signaling its ambitions to be a “polar expedition power,” China is now building a second icebreaker, giving it an icebreaking fleet equal to America’s. Russia, by far the largest Arctic nation, has 41 in all.

“The United States really isn’t even in this game,” Admiral Zukunft said at a conference in Washington this year.

He lamented the lack of urgency in Washington, contrasting it with the challenges of the Cold War, when the United States and the Soviet Union confronted each other in the Arctic and beyond. “When Russia put Sputnik in outer space, did we sit with our hands in pocket with great fascination and say, ‘Good for Mother Russia’?”

Polar Opposites

“The Arctic is one of our planet’s last great frontiers,” Mr. Obama declared when he introduced a national strategy for the region in May 2013. The strategy outlined the challenges and opportunities created by diminishing sea ice — from the harsh effects on wildlife and native residents to the accessibility of oil, gas and mineral deposits, estimated by the United States Geological Survey to include 13 percent of the world’s undiscovered oil and 30 percent of its natural gas.

In January, the president created an Arctic Executive Steering Committee, led by the director of the White House’s Office of Science and Technology, John P. Holdren. The committee is trying to prioritize the demands for ships, equipment and personnel at a time of constrained budgets.

Dr. Holdren said in an interview that administration officials were trying “to get our arms around matching the resources and the commitment we can bring to bear with the magnitude of the opportunities and the challenges” in the Arctic.

What kind of frontier the Arctic will be — an ecological preserve or an economic engine, an area of international cooperation or confrontation — is now the question at the center of the unfolding geopolitical competition. An increasing divergence over the answer has deeply divided the United States and its allies on one side and Russia on the other.

Since returning to the Kremlin for a third term in 2012, President Vladimir V. Putin has sought to restore Russia’s pre-eminence in its northern reaches — economically and militarily — with zeal that a new report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies compared to the Soviet Union’s efforts to establish a “Red Arctic” in the 1930s. The report’s title echoed the rising tensions caused by Russia’s actions in the Arctic: “The New Ice Curtain.”

Decades of cooperation in the Arctic Council, which includes Russia, the United States and six other Arctic states, all but ended with Moscow’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the continuing war in eastern Ukraine. In March, Russia conducted an unannounced military exercise that was one of the largest ever in the far north. It involved 45,000 troops, as well as dozens of ships and submarines, including those in its strategic nuclear arsenal, from the Northern Fleet, based in Murmansk.

The first of two new army brigades — each expected to grow to more than 3,600 soldiers — deployed to a military base only 30 miles from the Finnish border. The other will be deployed on the Yamal Peninsula, where many of Russia’s new investments in energy resources on shore are. Mr. Putin has pursued the buildup as if a 2013 protest by Greenpeace International at the site of Russia’s first offshore oil platform above the Arctic Circle was the vanguard of a more ominous invader.

“Oil and gas production facilities, loading terminals and pipelines should be reliably protected from terrorists and other potential threats,” Mr. Putin said when detailing the military buildup last year. “Nothing can be treated as trivial here.”

In Washington and other NATO capitals, Russia’s military moves are seen as provocative — and potentially destabilizing.

In the wake of the conflict in Ukraine, Russia has intensified air patrols probing NATO’s borders, including in the Arctic. In February, Norwegian fighter jets intercepted six Russian aircraft off Norway’s northern tip. Similar Russian flights occurred last year off Alaska and in the Beaufort Sea, prompting American and Canadian jets to intercept them. Russia’s naval forces have also increased patrols, venturing farther into Arctic waters. Of particular concern, officials said, has been Russia’s deployment of air defenses in the far north, including surface-to-air missiles whose main purpose is to counter aerial incursions that only the United States or NATO members could conceivably carry out in the Arctic.

“We see the Arctic as a global commons,” a senior Obama administration official said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss matters of national security. “It’s not apparent the Russians see it the same way we do.”

Russia has also sought to assert its sovereignty in the Arctic through diplomacy. This month, Russia resubmitted a claim to the United Nations to a vast area of the Arctic Ocean — 463,000 square miles, about the size of South Africa — based on the geological extension of its continental shelf.

The commission that reviews claims under the Convention on the Law of the Sea rejected a similar one filed in 2001, citing insufficient scientific evidence. But Russia, along with Canada and Denmark (through its administration of Greenland), have pressed ahead with competing stakes. Russia signaled its ambitions — symbolically at least — as early as 2007 when it sent two submersibles 14,000 feet down to seabed beneath the North Pole and planted a titanium Russian flag.

Although the commission might not rule for years, Russia’s move underscored the priority the Kremlin has given to expanding its sovereignty. The United States, by contrast, has not even ratified the law of the sea treaty, leaving it on the sidelines of territorial jockeying.

“Nobody cared too much about these sectors,” said Andrei A. Smirnov, deputy director for operations at Atomflot, which operates Russia’s fleet of six nuclear-powered icebreakers, “but when it turned out that 40 percent of confirmed oil and gas deposits were there, everybody became interested in who owns what.”

Some have questioned whether Russia, whose economy is sinking under the weight of sanctions and the falling price of oil, can sustain its efforts in the Arctic.

“It is rather difficult to find rationale for this very pronounced priority in the allocation of increasingly scarce resources,” said Pavel K. Baev of the Peace Research Institute Oslo. He added that Russian claims that it was protecting its economic interests from NATO were “entirely fictitious.”

“The only challenge to Russian exploitation of the Arctic came from Greenpeace,” he said.

American commanders are watching warily. The United States and its NATO allies still have significant military forces — including missile defenses and plenty of air power — in the Arctic, but the Army is considering reducing its two brigades in Alaska. The Navy, which has no ice-capable warships, acknowledged in a report last year that it had little experience operating in the Arctic Ocean, notwithstanding decades of submarine operations during the Cold War. While it saw little need for new assets immediately, it predicted that could change.

Adm. William E. Gortney, head of the Pentagon’s Northern Command and North American Aerospace Defense Command, said that Russia was increasing its capabilities after years of neglect but did not represent a meaningful threat, yet. “We’re seeing activity in the Arctic, but it hasn’t manifested in significant change at this point,” he said in a recent interview.

Despite concerns over the military buildup, others said that some of Russia’s moves were benign efforts to ensure the safety of ships on its Northern Sea Route, which could slash the time it takes to ship goods from Asia to Europe. Russia had pledged to take those steps as an Arctic Council member.

“Some of the things I see them doing — in terms of building up bases, telecommunications, search and rescue capabilities — are things I wish the United States was doing as well,” said Robert J. Papp Jr., a retired admiral and former commandant of the Coast Guard. He is now the State Department’s senior envoy on Arctic issues.

Less Ice, More Traffic

Aboard the Alex Haley, the crew made contact with each of the ships it encountered plowing the waters, recording details of the owners, courses and the number of crew members who might need to be plucked from the sea in case of disaster.

The cutter’s captain, Cmdr. Seth J. Denning, was a young ensign when he first crossed the Arctic Circle just north of the Bering Strait 19 years ago. “I never really realized that the Arctic was going to open up as much as it has — enough to allow this much activity,” he said. “I think it surprised many people.”

What had been a brief excursion for Ensign Denning when the Arctic was choked with ice has now become routine.

The Alex Haley — named after the author of “Roots,” who was a 20-year Coast Guard veteran — is one of five ships that the Coast Guard is deploying to the Arctic from June to October. It will be replaced by an advanced cutter, the Waesche, based in Alameda, Calif. The Coast Guard has also stationed two rescue helicopters at the airport at Deadhorse, the town where the Trans-Alaska Pipeline begins.

The deployments are part of an annual summer surge that was started in 2012 when Shell first explored the oil fields off Alaska’s North Slope. The challenges of the new mission have been exacting, given the vast distances and limited support infrastructure on land. For several days this month the Alex Haley’s only helicopter, which operates from a retractable hangar on the ship’s aft was out of service, awaiting a spare part that had to be flown in on several hops from North Carolina.

This year’s deployments are intended to assess the requirements for operating in the Arctic, but the expected increase in human activity there will put new demands on the service.

“As a maritime nation, we have responsibility for the safety and security of the people who are going to be using that ocean,” said Mr. Papp. “And we have a responsibility to protect the ocean from the people who will be using it.”

When President Obama travels to Alaska on Monday, becoming the first president to venture above the Arctic Circle while in office, he hopes to focus attention on the effects of climate change on the Arctic. Some lawmakers in Congress, analysts, and even some government officials say the United States is lagging behind other nations, chief among them Russia, in preparing for the new environmental, economic and geopolitical realities facing the region.

“We have been for some time clamoring about our nation’s lack of capacity to sustain any meaningful presence in the Arctic,” said Adm. Paul F. Zukunft, the Coast Guard’s commandant.

Aboard the Alex Haley, the increased activity in the Arctic was obvious in the deep blue waters of the Chukchi Sea. While the cutter patrolled one day this month, vessels began to appear one after another on radar as this ship cleared the western edge of Alaska and cruised north of the Arctic Circle.

There were three tugs hauling giant barges to ExxonMobil’s onshore natural gas project east of Prudhoe Bay. To the east, a flotilla of ships and rigs lingered at the spot where Royal Dutch Shell began drilling for oil this month. Not far away, across America’s maritime border, convoys of container ships and military vessels were traversing the route that Russia dreams of turning into a new Suez Canal.

The cutter, a former Navy salvage vessel built nearly five decades ago, has amounted to the government’s only asset anywhere nearby to respond to an accident, oil spill or incursion into America’s territory or exclusive economic zone in the Arctic.

To deal with the growing numbers of vessels sluicing north through the Bering Strait, the Coast Guard has had to divert ships like the Alex Haley from other core missions, like policing American fisheries and interdicting drugs. The service’s fleet is aging, especially the nation’s only two icebreakers. (The United States Navy rarely operates in the Arctic.) Underwater charting is paltry, while telecommunications remain sparse above the highest latitudes. Alaska’s far north lacks deepwater port facilities to support increased maritime activity.

The Competition for Resources in the Arctic

Areas with 50% or greater chance of large undiscovered oil and gas reserves

High seas and outer continental shelf

Extent of Arctic waters under Russian control

All these shortcomings require investments that political gridlock, budget constraints and bureaucracy have held up for years.

Russia, by contrast, is building 10 new search-and-rescue stations, strung like a necklace of pearls at ports along half of the Arctic shoreline. More provocatively, it has also significantly increased its military presence, reopening bases abandoned after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Russia is far from the only rival — or potential one — in the Arctic. China, South Korea and Singapore have increasingly explored the possibility that commercial cargo could be shipped to European markets across waters — outside Russia’s control — that scientists predict could, by 2030, be ice-free for much of the summer.

In 2012, with great fanfare, China sent a refurbished icebreaker, the Xuelong, or Snow Dragon, across one such route. Signaling its ambitions to be a “polar expedition power,” China is now building a second icebreaker, giving it an icebreaking fleet equal to America’s. Russia, by far the largest Arctic nation, has 41 in all.

“The United States really isn’t even in this game,” Admiral Zukunft said at a conference in Washington this year.

He lamented the lack of urgency in Washington, contrasting it with the challenges of the Cold War, when the United States and the Soviet Union confronted each other in the Arctic and beyond. “When Russia put Sputnik in outer space, did we sit with our hands in pocket with great fascination and say, ‘Good for Mother Russia’?”

Polar Opposites

“The Arctic is one of our planet’s last great frontiers,” Mr. Obama declared when he introduced a national strategy for the region in May 2013. The strategy outlined the challenges and opportunities created by diminishing sea ice — from the harsh effects on wildlife and native residents to the accessibility of oil, gas and mineral deposits, estimated by the United States Geological Survey to include 13 percent of the world’s undiscovered oil and 30 percent of its natural gas.

In January, the president created an Arctic Executive Steering Committee, led by the director of the White House’s Office of Science and Technology, John P. Holdren. The committee is trying to prioritize the demands for ships, equipment and personnel at a time of constrained budgets.

Dr. Holdren said in an interview that administration officials were trying “to get our arms around matching the resources and the commitment we can bring to bear with the magnitude of the opportunities and the challenges” in the Arctic.

What kind of frontier the Arctic will be — an ecological preserve or an economic engine, an area of international cooperation or confrontation — is now the question at the center of the unfolding geopolitical competition. An increasing divergence over the answer has deeply divided the United States and its allies on one side and Russia on the other.

Since returning to the Kremlin for a third term in 2012, President Vladimir V. Putin has sought to restore Russia’s pre-eminence in its northern reaches — economically and militarily — with zeal that a new report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies compared to the Soviet Union’s efforts to establish a “Red Arctic” in the 1930s. The report’s title echoed the rising tensions caused by Russia’s actions in the Arctic: “The New Ice Curtain.”

Decades of cooperation in the Arctic Council, which includes Russia, the United States and six other Arctic states, all but ended with Moscow’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the continuing war in eastern Ukraine. In March, Russia conducted an unannounced military exercise that was one of the largest ever in the far north. It involved 45,000 troops, as well as dozens of ships and submarines, including those in its strategic nuclear arsenal, from the Northern Fleet, based in Murmansk.

The first of two new army brigades — each expected to grow to more than 3,600 soldiers — deployed to a military base only 30 miles from the Finnish border. The other will be deployed on the Yamal Peninsula, where many of Russia’s new investments in energy resources on shore are. Mr. Putin has pursued the buildup as if a 2013 protest by Greenpeace International at the site of Russia’s first offshore oil platform above the Arctic Circle was the vanguard of a more ominous invader.

“Oil and gas production facilities, loading terminals and pipelines should be reliably protected from terrorists and other potential threats,” Mr. Putin said when detailing the military buildup last year. “Nothing can be treated as trivial here.”

In Washington and other NATO capitals, Russia’s military moves are seen as provocative — and potentially destabilizing.

In the wake of the conflict in Ukraine, Russia has intensified air patrols probing NATO’s borders, including in the Arctic. In February, Norwegian fighter jets intercepted six Russian aircraft off Norway’s northern tip. Similar Russian flights occurred last year off Alaska and in the Beaufort Sea, prompting American and Canadian jets to intercept them. Russia’s naval forces have also increased patrols, venturing farther into Arctic waters. Of particular concern, officials said, has been Russia’s deployment of air defenses in the far north, including surface-to-air missiles whose main purpose is to counter aerial incursions that only the United States or NATO members could conceivably carry out in the Arctic.

“We see the Arctic as a global commons,” a senior Obama administration official said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss matters of national security. “It’s not apparent the Russians see it the same way we do.”

Russia has also sought to assert its sovereignty in the Arctic through diplomacy. This month, Russia resubmitted a claim to the United Nations to a vast area of the Arctic Ocean — 463,000 square miles, about the size of South Africa — based on the geological extension of its continental shelf.

The commission that reviews claims under the Convention on the Law of the Sea rejected a similar one filed in 2001, citing insufficient scientific evidence. But Russia, along with Canada and Denmark (through its administration of Greenland), have pressed ahead with competing stakes. Russia signaled its ambitions — symbolically at least — as early as 2007 when it sent two submersibles 14,000 feet down to seabed beneath the North Pole and planted a titanium Russian flag.

Although the commission might not rule for years, Russia’s move underscored the priority the Kremlin has given to expanding its sovereignty. The United States, by contrast, has not even ratified the law of the sea treaty, leaving it on the sidelines of territorial jockeying.

“Nobody cared too much about these sectors,” said Andrei A. Smirnov, deputy director for operations at Atomflot, which operates Russia’s fleet of six nuclear-powered icebreakers, “but when it turned out that 40 percent of confirmed oil and gas deposits were there, everybody became interested in who owns what.”

Some have questioned whether Russia, whose economy is sinking under the weight of sanctions and the falling price of oil, can sustain its efforts in the Arctic.

“It is rather difficult to find rationale for this very pronounced priority in the allocation of increasingly scarce resources,” said Pavel K. Baev of the Peace Research Institute Oslo. He added that Russian claims that it was protecting its economic interests from NATO were “entirely fictitious.”

“The only challenge to Russian exploitation of the Arctic came from Greenpeace,” he said.

American commanders are watching warily. The United States and its NATO allies still have significant military forces — including missile defenses and plenty of air power — in the Arctic, but the Army is considering reducing its two brigades in Alaska. The Navy, which has no ice-capable warships, acknowledged in a report last year that it had little experience operating in the Arctic Ocean, notwithstanding decades of submarine operations during the Cold War. While it saw little need for new assets immediately, it predicted that could change.

Adm. William E. Gortney, head of the Pentagon’s Northern Command and North American Aerospace Defense Command, said that Russia was increasing its capabilities after years of neglect but did not represent a meaningful threat, yet. “We’re seeing activity in the Arctic, but it hasn’t manifested in significant change at this point,” he said in a recent interview.

Despite concerns over the military buildup, others said that some of Russia’s moves were benign efforts to ensure the safety of ships on its Northern Sea Route, which could slash the time it takes to ship goods from Asia to Europe. Russia had pledged to take those steps as an Arctic Council member.

“Some of the things I see them doing — in terms of building up bases, telecommunications, search and rescue capabilities — are things I wish the United States was doing as well,” said Robert J. Papp Jr., a retired admiral and former commandant of the Coast Guard. He is now the State Department’s senior envoy on Arctic issues.

Less Ice, More Traffic

Aboard the Alex Haley, the crew made contact with each of the ships it encountered plowing the waters, recording details of the owners, courses and the number of crew members who might need to be plucked from the sea in case of disaster.

The cutter’s captain, Cmdr. Seth J. Denning, was a young ensign when he first crossed the Arctic Circle just north of the Bering Strait 19 years ago. “I never really realized that the Arctic was going to open up as much as it has — enough to allow this much activity,” he said. “I think it surprised many people.”

What had been a brief excursion for Ensign Denning when the Arctic was choked with ice has now become routine.

The Alex Haley — named after the author of “Roots,” who was a 20-year Coast Guard veteran — is one of five ships that the Coast Guard is deploying to the Arctic from June to October. It will be replaced by an advanced cutter, the Waesche, based in Alameda, Calif. The Coast Guard has also stationed two rescue helicopters at the airport at Deadhorse, the town where the Trans-Alaska Pipeline begins.

The deployments are part of an annual summer surge that was started in 2012 when Shell first explored the oil fields off Alaska’s North Slope. The challenges of the new mission have been exacting, given the vast distances and limited support infrastructure on land. For several days this month the Alex Haley’s only helicopter, which operates from a retractable hangar on the ship’s aft was out of service, awaiting a spare part that had to be flown in on several hops from North Carolina.

This year’s deployments are intended to assess the requirements for operating in the Arctic, but the expected increase in human activity there will put new demands on the service.

“As a maritime nation, we have responsibility for the safety and security of the people who are going to be using that ocean,” said Mr. Papp. “And we have a responsibility to protect the ocean from the people who will be using it.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.