The war on palm oil - Is it possible to avoid taking sides?

Jessica Shankleman wrestles with the environmental and ethical dilemmas presented by the global palm oil industry

Jessica Shankleman wrestles with the environmental and ethical dilemmas presented by the global palm oil industryOne of the main challenges faced by environmental journalists is navigating one’s way through a minefield of green PR spin. Every company seeks to present its environmental initiatives in the best possible light, even if their actions are pretty unimpressive, or in some cases even damaging to the environment. Meanwhile, many green NGOs are keen to cast companies in the worst possible light, even when there are numerous, complex explanations for their actions.

So when BusinessGreen was last month invited on a press trip funded and organised by Malaysian palm oil company Sime Darby and intended to demonstrate the company’s sustainability credentials, we were faced with a dilemma. Should we accept, fully aware that we could be the victim of greenwash, or decline and miss the opportunity to gain an insight into how one of the world’s most environmentally controversial industries operates?

Some media organisations turn down such invitations due to impartiality policies that refuse trips that have been funded by a company they are going to write about. However, for right or wrong, funded trips are in fact remarkably common across the media (most technology conferences simply would not be reported without IT companies willing to cover journalists’ expenses), and while national papers have access to travel budgets, most business-to-business titles frequently have to decide whether to accept a company’s hospitality or forgo the story altogether.

As a result, BusinessGreen decided on this occasion to accept the offer on the grounds that it would provide an invaluable opportunity to learn more about the industry. However, in the interests of transparency, every article I published during the trip was postscripted with a disclosure that the trip was funded by Sime Darby.

Armed with company reports, dossiers from NGOs and the World Bank, and a fistful of newspaper clippings, I boarded the plane, determined to discover if this conglomerate, which appeared to be at the heart of an industry reputed to have an appalling environmental record, could convince a group of European journalists that it really was committed to sustainability.

Throughout the week Sime Darby presented a pretty convincing case to demonstrate that it operates higher sustainability standards than many other plantation companies. For example, it insists it does not locate palm oil plantations on virgin forests, has a zero-burning replanting technique, and is aiming to certify all its plantations as sustainable by the end of the year with the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil.

However, these apparent improvements cannot disguise the fact that only six per cent of the current global supply of palm oil meets sustainability standards, suggesting the industry is only just beginning to tackle its environmental problem.

The challenge faced by Sime Darby and those other palm oil firms committed to improving their sustainability credentials is that the debate about the industry’s environmental impact has become so polarised that it is difficult to dispassionately assess the effectiveness of their emerging green policies.

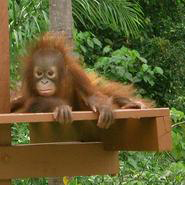

For example, the debate intensified again while I was on the trip, when the Adam Smith Institute published a “pro-palm oil” report, in which author Keith Boyfield argued that NGOs have overblown the impacts of palm oil plantations on the endangered orangutan in order to help raise funds. Meanwhile, the Guardian’s Leo Hickman responded by suggesting that the report formed part of a new “offensive” launched by the industry to improve its reputation in Europe.

He has a point; the industry has undoubtedly stepped up its communication efforts and the press trip I was on was clearly part of that. But does that necessarily make it wrong?

Critics maintain that the palm oil industry has led to widespread deforestation in Malaysia (and travelling around the country makes it clear to see that palm oil plantations dominate the agricultural sector) with further felling likely in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, where an estimated 10 million to 15 million hectares of rainforest are currently gazetted for conversion to palm oil plantation.

Similarly, as palm oil companies move into new territories in Africa, deforestation will accelerate as a result. Sime Darby insisted that as it beefs up its presence in Africa it will embrace the highest possible sustainability standards on its plantations and never use deforested land. But others may not be as responsible and there are still concerns that converting secondary or degraded forest into palm oil plantations can still eat into available agricultural land, inadvertently fuelling deforestation further down the line.

Much of this is the standard argument put forward by NGOs critical of the palm oil industry, and any attempt to push back against it by the palm oil industry is immediately dismissed as greenwash.

But on talking to a wide range of people in Malaysia it became clear that many believe palm oil is a positive industry that has helped to drive development and lift people out of poverty. Some even accuse the West of hypocrisy for condemning unsustainable practices, when we deforested our own land in the name of development during the industrial revolution. Moreover, the palm oil industry’s expansion has been primarily driven by demand from western customers for food, biofuel and cosmetics.

The palm oil industry undoubtedly has a terrible environmental record and in some cases even stands accused of human rights violations. But is it in anyone’s interest to dismiss out of hand attempts by some firms to reduce the environmental impact of their operations, particularly when they are only responding to western demand? Like any other industry, the palm oil sector has its problems and needs to be encouraged to improve its environmental performance through a carefully balanced mix of incentives and criticism. The polarised nature of the debate over palm oil makes that balance extremely difficult to achieve.

I am no apologist for the palm oil industry – the evidence for its involvement in deforestation is compelling and has been ignored and downplayed by the sector for too long. I am also fully aware that the trip I was on was designed to show only positive aspects of the industry and appalling practices undoubtedly continue elsewhere. However, if we are to address the challenges the industry faces, we must accept the role played by unsustainable levels of demand and a failure to adequately promote best practices. The debate is complex and palm oil companies, particularly those working to improve their environmental performance, should not be vilifed through blanket criticism.

But then again, maybe I have just been greenwashed.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.