The US needs 22m acres for the solar energy transition – here’s what that looks like

The Bureau of Land Management proposed using 22m acres of public land for solar projects – roughly the size of Maine, or an area larger than Scotland.

If the US is to rid itself of fossil fuels then one of its primary replacements, solar energy, is going to need land. A lot of land.

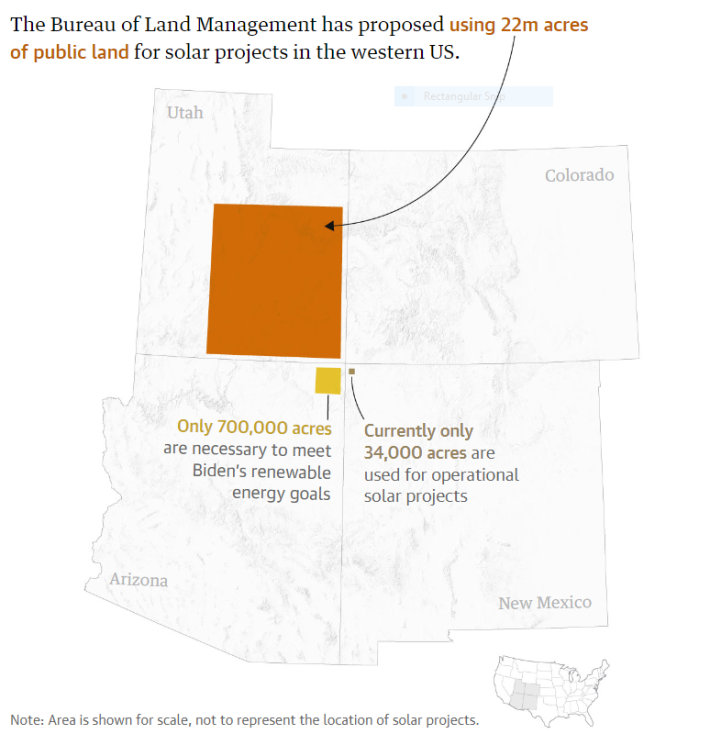

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM), which oversees more of the public realm than any other federal government agency, has outlined exactly how much of western America should be made available for solar panels and their associated cables and transformers – 22m acres. That is roughly the size of Maine, or an area larger than Scotland.

This total, part of a new administration plan to accelerate solar energy in the US west, will give the US “maximum flexibility” to meet climate goals, the BLM said.

A smaller area of this available land, around 700,000 acres, will definitely need to be dotted with solar panels to meet a goal set by Joe Biden to have a 100% clean electricity grid by 2035. This is still a big leap from the status quo, where only around 34,000 acres of bureau land is used for solar.

Solar may currently contribute little more than 3% of the US’s electricity generation but it is having something of a moment, with projects bolstered by Biden’s huge tranche of clean energy subsidies. The BLM is progressing several major solar projects – the largest, in Nevada, is set to be 5,500 acres in size, enough to power more than 200,000 homes – and utility-scale solar generation is expected to grow 75% by next year compared to last, adding 79,000 megawatts of new capacity.

The scale of this growth, however, has unsettled some residents who oppose solar farms in their communities or on farmland, as well as environmentalists who fret over the fate of species such as the desert tortoise as seemingly empty habitat is upended into a new, mirrored, reality.

Even if land is used for a solar project, though, it can still be utilized for some other agricultural uses and BLM said it would prefer development to take place within 10 miles of existing transmission lines, with exclusions for habitat and cultural reasons.

Green groups say a detente can be found between the desire to protect food-producing land and habitat for threatened species while also tackling a climate crisis that menaces both people and wildlife.

“Renewable energy on public lands can be a win-win-win,” said Justin Meuse, a campaigner at the Wilderness Society. “It’s imperative and it’s possible.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.