The Right to Water

The right to

water was affirmed by the UN General Assembly today. 122 countries

voted in favor, none against, and 41, including the United States

and Canada abstaining.

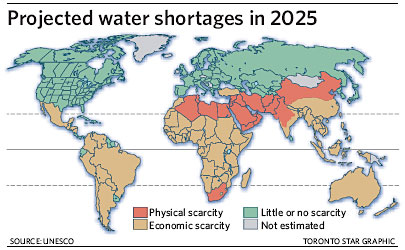

Over two billion people live in water-stressed regions, and more

than one billion live without safe supplies of drinking water.

Unfortunately for them the UN vote may not have much practical

meaning. And while the inclusion of the right to clean water in the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights has no legal standing;

it is an important political step forward in the

resolution of a growing global issue, the access to clean safe

drinking water.

The 192-nation body approved a resolution put forward by Bolivia

and signed by 33 other states to add access to water to its human

rights declaration.

Humanitarian and political dimensions of the right to water

issue dominated pre-vote discussions and lobbying, but there are

important business dimensions at stake as well.

A report issued in November last years by the 2030 Water

Resources Group shows that one-third of the world’s population

would have a 50% deficit in water supply by 2030 if no action is

taken, but that growing water scarcity can be mitigated affordably

and sustainably if action is taken now.

The report states that the growing competition for scarce water

resources represents a growing business risk, a major economic

threat, and a challenge for the sustainability of communities and

the ecosystems upon which they rely. It is an issue that has

serious implications for the stability of countries in which

businesses operate, and for industries whose value chains are

exposed to water scarcity.

The humanitarian dimensions of the right to water issue were

highlighted recently by former Soviet Union President Mikhail

Gorbachev. In an opinion piece published in the New York Times he

stated “Water, the basic ingredient of life, is among the world’s

most prolific killers. At least 4,000 children die every day from

water-related diseases. In fact, more lives have been lost after

World War II due to contaminated water than from all forms of

violence and war.”

Gorbachev singled out the United States and Canada as among the

very few developed nations that had not formally embraced the right

to safe water, and urged U.S. President Barack Obama to extend his

championship of human rights and sustainable development around the

world into support for access to water as a human right.

Maude Barlow, National Chairperson of the Council of Canadians

and former advisor to the UN on water issues noted “When the 1948

Universal Declaration on Human Rights was written, no one could

foresee a day when water would be a contested area. But in 2010, it

is not an exaggeration to say that the lack of access to clean

water is the greatest human rights violation in the world.”

An in-depth analysis of the world’s water resources published by

target=”_blank”>UN Water, a special United Nations initiative

identifies water as the primary medium through which climate change

influences the Earth’s ecosystem and thus the livelihood and

well-being of societies.

Higher temperatures and changes in extreme weather conditions

are projected to affect availability and distribution of rainfall,

snowmelt, river flows and groundwater, and further deteriorate

water quality, it notes.

Water stress is already high, particularly in many developing

countries; improved management is critical to ensure sustainable

development. Water resources management affects almost all aspects

of the economy, in particular health, food production and security;

domestic water supply and sanitation; energy and industry; and

environmental sustainability. If addressed inadequately, management

of water resources will jeopardize progress on poverty reduction

targets and sustainable development in all economic, social and

environmental dimensions.

The

target=”_blank”>resolution on water as a basic human right as

drafted by Bolivia says internationally endorsed water rights would

‘entitle everyone to available, safe, acceptable, accessible and

affordable water and sanitation.’ It declares that countries unable

to deliver water to their populations - despite their best efforts

- should be helped through ‘international co-operation and

assistance’.

This is a clear signal for increased aid to the Third World for

water development initiatives from more developed economies.

One of the economic dimensions motivating the Bolivian draft was

that country’s disastrous experiment with the privatization of

water services.

Two concessions for the control of water to private companies

in Bolivia - part of a condition of a World Bank loan of

US$20 million to the Bolivian government in 1997 - were rejected

through popular uprisings. Protests escalated to the point that the

Bolivian government declared a state of martial law, and eventually

the companies involved were forced to abandon their operations.

Notwithstanding that economic and social factors such as

political corruption and in the case of Bolivia a pre-existing

public anti-privatization sentiment that contributed to the failure

of water privatization in that country, the pricing of water in the

developing world is recognized as a critical factor in realizing

the UN’s Millennium Development Goals pertaining to water.

The

target=”_blank”>UN Water report stresses five key requirements

that the global community will have to address in the years

ahead.

1. Planning and applying new

investments (for example, reservoirs, irrigation systems, capacity

expansions, levees, water supply, wastewater treatments, ecosystem

restoration).

2. Adjusting operation, monitoring

and regulation practices of existing systems to accommodate new

uses or conditions (for example, ecology, pollution control,

climate change, population growth).

3. Working on maintenance, major

rehabilitation and re-engineering of existing systems (for example,

dams, barrages, irrigation systems, canals, pumps, rivers,

wetlands).

4. Making modifications to processes

and demands for existing systems and water users (for example,

rainwater harvesting, water conservation, pricing, regulation,

legislation, basin planning, funding for ecosystem services,

stakeholder participation, consumer education and awareness).

5. Introducing new efficient

technologies (for example, desalination, biotechnology, drip

irrigation, wastewater reuse, recycling, solar panels).

The overall cost to address these challenges is staggering. The

2030 Water Resources Group report suggests that closing the future

“water gap” will cost $50 billion to $60 billion per year of

investment by expanding measures already being taken in some

communities to boost efficiency, augment supply, or lessen the

water-intensity of the economy.

But it too noted that in the world of water resources, economic

data is insufficient, management is often opaque, and stakeholders

are insufficiently linked. As a result, many countries struggle to

shape implementable, fact-based water policies, and water resources

face inefficient allocation and poor investment patterns because

investors lack a consistent basis for economically rational

decision-making.

Indeed the question of pricing what in many cases has been a

free good is fraught with complexity and is looked at with dread by

politicians the world over.

Water will be a key topic of discussion at the GLOBE 2012

Conference, scheduled for March 14th to 16th 2012 in Vancouver

Canada.

Source: www.thestar.com