The Amazon is the planet's counterweight to global warming, a place of stupefying richness under relentless assault

TRAIRÃO, Brazil—Jaim Teixeira surveys his property from the back of a motorcycle, wearing jeans and a long-sleeved, sun-proof shirt to shield him from the jungle’s breathtaking heat.

It’s the end of the dry season and, like everything and everyone in this part of the Amazon, the lean, 51-year-old rancher is covered in a fine brick-red dust.

Nearby, a plume of smoke rises at the edge of the jungle canopy, heading skyward until it blurs into an indistinct haze. Burning trees crackle and spit. One falls with a whack. Then another.

Teixeira lit the blaze the previous day to clear grazing land for his cattle. Brazil’s ranchers and rainforest frontiersmen call this limpeza. Cleaning. It’s the most expedient way to tame a jungle that stretches for thousands of miles in every direction.

“I know it’s illegal,” he says, gesturing toward the smoke. “If I had a salary, I wouldn’t need to do it. But how else can I feed my family?”

No license allows a person to burn the Amazon’s ancient trees.

“For virgin forest,” Teixeira said, “you have to do it illegally.”

So people do.

The Amazon is enveloping and lush, a place of stupefying richness. But a powerful web of extractive forces is also at work here.

Every day, thousands of miners, loggers, farmers and ranchers burn or cut roughly 10,000 acres of forest, working to satisfy a growing demand for the resources it contains. They are tiny cogs in a sprawling global machine that has destroyed nearly one-fifth of the Brazilian rainforest—an area about the size of California—over the last 35 years, driving more than 10,000 plant and animal species toward extinction.

The Amazon is the biggest in a belt of forests that wraps the planet’s midsection. It is a jungle so hot and humid, it makes its own rain. Its web of rivers is the largest in the world and contains about one-sixth of the world’s fresh water.

The rainforest is home to more than 10 percent of all plant and animal species, with new ones being discovered, on average, every other day. Under its canopy, insects fly around, looking like Pixar characters; rare, tiny mammals with humanly earnest faces scamper along branches, bird song rings through the leaves. Everything is pulsing and oxygenated, cycling through life and death and back to life.

Within this cycle, the Amazon’s soils and vegetation store between 150 billion to 200 billion tons of carbon—roughly five times the world’s annual greenhouse gas emissions, helping to stabilize the atmosphere and provide a counterweight to global warming.

If the planet loses the Amazon, it will be almost impossible to maintain that balance.

“A vast amount of carbon would be converted from organic matter into carbon dioxide and that would add to the carbon dioxide we’re already putting into the atmosphere from burning fossil fuels,” said Scott Denning, an atmospheric scientist with Colorado State University. “That would be a catastrophe for humanity and for everything else.”

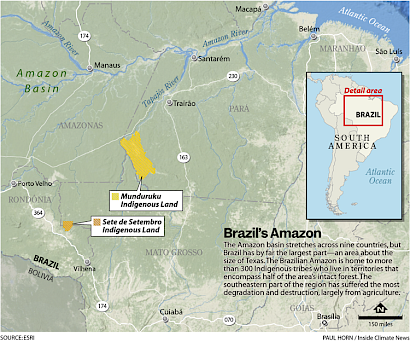

Parts of the Amazon are spread across nine countries, from Bolivia in the south to Venezuela and Colombia in the north, but Brazil has by far the largest piece, with 60 to 70 percent of the rainforest. Brazil also suffers from some of the highest rates of rainforest destruction and degradation in the tropics.

For about a decade, beginning in 2009, deforestation rates declined and then stabilized, after the Brazilian government imposed stronger protections for the rainforest. But in 2019, with the election of President Jair Bolsonaro, a far rightwing former military captain, that trend quickly began to reverse. Since he took office, the annual rate of deforestation has risen sharply, increasing nearly 60 percent from 2020, according to a Brazilian research institute. Bolsonaro has called government data on deforestation a “lie.”

For about a decade, beginning in 2009, deforestation rates declined and then stabilized, after the Brazilian government imposed stronger protections for the rainforest. But in 2019, with the election of President Jair Bolsonaro, a far rightwing former military captain, that trend quickly began to reverse. Since he took office, the annual rate of deforestation has risen sharply, increasing nearly 60 percent from 2020, according to a Brazilian research institute. Bolsonaro has called government data on deforestation a “lie.”

In November, at the United Nation’s annual climate negotiations held in Glasgow, Brazil promised to end illegal deforestation by 2028, but a new government report revealed that deforestation had risen—yet again—over the previous year.

The reversal has been so stark, so convincingly tied to Bolsonaro’s anti-environmental policies and rhetoric, his critics say, that advocacy groups, Indigenous tribes and some of the world’s most prominent human rights lawyers believe the president should be prosecuted. Bolsonaro’s role in destroying the Amazon, they believe, makes him a criminal on a par with genocidal dictators or the architects of war crimes.

In October, the day before Teixeira set his forest ablaze and as thousands of small fires burned across the Amazon, an Austrian environmental group became the latest to accuse Bolsonaro of crimes against humanity, in a complaint filed with the International Criminal Court in The Hague. The complaint follows three others, filed on behalf of Brazilian Indigenous groups.

The complaints could help persuade the international court to adopt a new crime—ecocide—as the fifth in the list of the world’s gravest offenses, along with genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and waging illegal war. It would be the first crime to be added since the trial of the Nazis at Nuremberg after World War II, and the first to make nature, not humanity, the victim.

The crime of ecocide was officially defined this year by an independent legal panel as “unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and widespread or long-term damage to the environment.”

The complaints to the court will take years to play out, if they ever do. But they bring to the world’s legal stage a longstanding conflict between industries that have exploited the Amazon’s resources—and are the foundation of the modern Brazilian economy—and the Indigenous people who’ve lived in the rainforest for millenia.

The outcome of that conflict now has consequences for the entire planet.

Indigenous tribes in the Amazon are on the frontline of the climate battle in ways that the rest of the world’s population is not, and increasingly, scientific research demonstrates that Indigenous land rights are critical for solving the climate crisis. When tribes have clear ownership of their land, the forest remains intact. And when the forest remains intact, otherwise dangerous carbon stays locked away in roots and soils, leashed by Indigenous stewardship

“Without the forest, we Indigenous people cannot live and humanity cannot live,” said Chief Almir Narayamoga Suruí, one tribal leader represented in the complaints, in an interview at his village in the Sete de Setembro reservation. So, he added, Bolsonaro “is making genocide against the world.”

‘Beef, Bibles and Bullets’

Hundreds of thousands of Jaim Teixeiras live across the Amazon and share a similar story.

Like Teixeira, many came from the south, from Rio de Janeiro or São Paulo, to escape lives of crushing urban poverty. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Brazilian government gave more than 1 million Brazilians plots of land along new army-built roads that opened the Amazon up to development. The one-room houses of these settlers are everywhere still, overgrown with vines, abandoned after their owners sold their land.

Teixeira remembers the day he arrived in the north from Rio, July 18, 1980, the date his modest success story began to take shape.

As a young man he bought some land. Then he bought some more. He got married and had three kids. He built a house with a clay-tile roof and electricity. Teixeira now has 140 cattle on 500 acres—small compared to some, but an accomplishment for a guy who never went to high school. He’s carved a life out of the jungle.

Teixeira doesn’t know where his cattle end up. He sells them in town to a man who brings them north to Santarem or Itaituba. His ranch is just one of tens of thousands that provide cattle for the Brazilian meat industry, with JBS—the world’s largest meat company, headquartered in São Paulo—at the top.

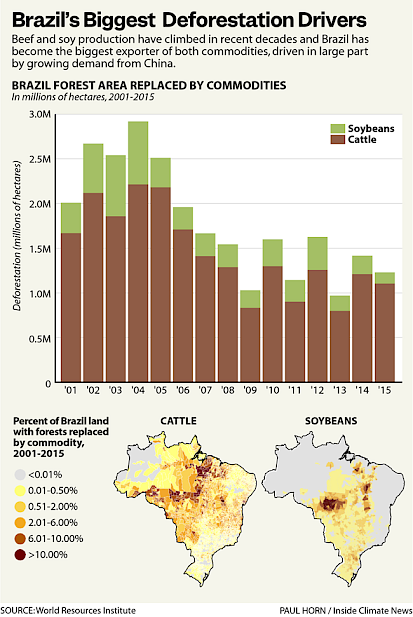

Since the 1960s, when government policies pushed the agricultural frontier deeper into the Amazon, the number of cows in the country has exploded. Back then, on the outskirts of Brasilia, the modernist, planned capital city, JBS was a small ranching operation, but it grew quickly as it fed the appetites of the new city. The Amazon was home to about 5 million cows. Today, it has nearly 90 million beef cattle, nearly half of Brazil’s total 200 million—more than any other country in the world. This explosion of cattle, propelled by a demand for burgers and steaks, is the main driver of the Amazon rainforest’s disappearance. Brazilian ranching is the largest source of deforestation-related greenhouse gas emissions in Latin America.

For poor farmers like Teixeira, the meat industry has meant a living. To raise cattle, all you need to do is burn some forest and let a few cows graze off the grasses that grow in the newly-cleared soil. You don’t need equipment or much capital. You need land, but there’s plenty of it. Many ranchers just start clearing and grazing on land they don’t officially own. More than half the current deforestation in the Amazon occurs on public land that’s been illegally grabbed.

The big Brazilian meat companies—JBS, along with Marfrig and Minerva—have promised to stop buying cattle from deforested land.

A spokeswoman for Marfrig said the company aims to eliminate deforestation throughout its supply chain by 2025 in the Amazon and 2030 in the Cerrado. A spokeswoman for Minerva said “100 [percent] of purchases made by Minerva Foods are monitored in all operating regions” of Brazil and pointed to a government audit showing high rates of compliance with its deforestation efforts. A spokesman for JBS said the company has “no tolerance for illegal deforestation” and intends to “achieve a completely illegal deforestation-free supply chain by 2025.”

But critics say the supply chain is stubbornly murky and these commitments don’t add up to much. A rancher moves his cows to another rancher, who raises the animals on pasture that was not recently cleared, earning the cattle a clean record.

Across the vastness of the eastern and southern Amazon—the so-called Arc of Deforestation—white cows cover every green field and gather for shade at the bases of the trees left behind. From the sky they look like grains of rice.

Many of the cows are raised by wealthy ranchers with thousands of acres. Some of them are mayors of towns or members of the Brazilian congress. Some are just small-scale ranchers like Teixeira. As a whole, they are Bolsonaro’s rural power base, the ruralistas who believe in “beef, bibles and bullets,” as the saying goes.

The Bolsonaro administration did not reply to requests from Inside Climate News for comment for this article.

Bolsonaro’s pro-development, anti-environment rhetoric has emboldened ranchers, along with loggers and miners, to clear more rainforest with seeming impunity. But burning and cutting virgin forest is still illegal, and federal agencies, though weakened under Bolsonaro, try to punish violators. Agents from IBAMA, the government’s environmental agency, can destroy farm machinery and levy fines on ranch lands, making them impossible to sell.

For Teixeira, and thousands like him, it’s worth the steep risk. Tomorrow or the day after, when the flames die down, he’ll plant grass seeds in the ashes and soon his cows will graze there.

“We have no education. We don’t have anything,” he said. “This is what we have to do.”

‘An Island of Trees’

When João Cohen moved to his patch of the Amazon 30 years ago, he killed 36 deadly vipers as he cleared land to plant manioc. The place was wild and tangled, with no one around. He reached it on foot, walking a narrow path a couple miles from the main road that leads to the port city of Santarem. Sometimes jaguar footsteps were so freshly printed in the path’s red soil, he swore they were still warm.

Now his property is an island of trees, surrounded by soybean fields that stretch to the horizon, a green, export-bound sea. Cohen, 78, spends most of his time these days either fending off offers to buy his land or making sure his neighbors are not encroaching on it.

“This little piece of forest is protected,” he said, sitting stern-faced on the porch of his bright blue house. “It’s not for sale. It’s not for sale. How many times can I say ‘No’?” When the brother of a local mayor made an offer and with it, an implied threat, Cohen asked his daughter to call twice a day to check on him.

After buying the land decades ago, Cohen cleared just enough of it to make a living for himself, growing black pepper, mostly. He has a desirable freshwater spring and a running creek to water his crops. But deforestation to make room for the massive soybean farms has changed not just the landscape but the climate. Now sometimes, the creek runs dry.

“When I first came here the weather was so different. There was so much forest,” he said. “The chainsaws ate everything.” Now the rain barely comes, and when it does, the storms are so violent they scare him.

Science backs up what Cohen is experiencing firsthand. With more forests cut down for soy and cattle, droughts are getting worse in the Amazon; rains are becoming more erratic and intense.

The soybean boom in Brazil has transformed the country into the world’s biggest producer of soy, overtaking the United States. In the process, soybean growers have gobbled up giant swaths of the Amazon. An agreement signed in 2006 by the major grain traders to stop buying soy from recently deforested land was successful in decreasing deforestation in the Amazon. But critics say that pushed soy production into the neighboring Cerrado, a savannah biome that’s critically important for climate stabilization but gets less attention than its jungly neighbor. Roughly half of the Cerrado has been destroyed, much of it for soy and much of it illegally.

Most of Brazil’s soy goes to China—more than $20 billion in sales a year—as animal feed for that country’s ever-expanding hog industry, sold to the Chinese by American companies, including Bunge, ADM and Cargill, the biggest privately-held company in the United States.

There is a pattern in the Amazon: The loggers come first, often followed by miners who use the inroads that loggers have cut in the jungle. Then ranchers move in and graze on the pasture where the trees stood, and farmers plant soy and corn in those pastures. More recently, demand for soy has become so great that parts of the Amazon and the neighboring Cerrado region are being converted directly to soy.

“It was beautiful, dense forest five years ago. In this area there were no gigantic farms,” said Iza Maria Castro Dos Santos Pueblo Tapuia, an Indigenous activist who lives in Santarem. “Today, there are giant bulldozers. It used to be chainsaws. What they used to chop down in a day, they can do in an hour.”

A spokeswoman for ADM said the company does not source its products from any newly deforested areas in the Amazon. A spokeswoman for Cargill said the company is committed to eliminating deforestation from its supply chains “in the shortest time possible” and that it “will not source from farmers who clear land illegally or in protected areas.” The company has “the same expectations of our suppliers,” she said. Bunge did not respond to requests for comment for this article, but has said in past statements that it will eliminate deforestation from its supply chain by 2025.

The pressure will only ramp up, experts say. Soy farming across Brazil is predicted to grow even more in the coming years, with new “agricultural frontiers” opening up, especially in northern parts of the country. There are plans in process for more ports along more rivers and a new railway to move grain to the waterways.

That means more virgin forest and savannah converted to farmland, and more small-scale landowners standing in the crosshairs of an expanding industry.

Santarem, near the confluence of the Tapajós and Amazon rivers, sits at the terminus of BR 163—the so-called Soybean Highway—which runs 2,200 miles north through the Cerrado and the Amazon basin. During the dry season, from May to October, a disjointed convoy of double-hulled, 90-foot-long tractor-trailers move grain northward along its potholed, deeply rutted surface. They pass by frontier towns that have formed along this artery, with their journeyman hotels, chainsaw dealerships and slaughterhouses, between them an unrelenting panorama of soybean fields, with each grain elevator poking up into the sky like a giant Oz-ian Tin Man.

The road stops at the edge of the Tapajós, where a towering grain terminal built by Cargill shuttles soy off to the rest of the world. Tourists walk along the river promenade at night, eating ice cream, with the terminal lights on the roller coaster-shaped Cargill facility twinkling in the near distance. If this wasn’t the Amazon, you might mistake it for a seaside amusement park.

But the facility is not a popular place with some. Cargill built it on a public beach, near an archeologically important Indigenous site, say critics, who took the company to court and lost.

“It’s like a monster over there,” said Tapuia, who was part of the effort to derail the Cargill terminal plan.

That monster has helped to make Santarem a prosperous place, with schools, hospitals and infrastructure—a place where an old man like Cohen might be safer than alone on an island of trees surrounded by soybean fields. His daughter wants her father to move to the city, away from the pressures of the jungle.

He won’t.

“There’s no way anyone will touch my forest,” he said. “I want to build a house under the mango tree and live there forever in my eternal home. No one will ever buy this land. I’ll scare them off like a lost ghost.”

‘It’s an Ecocide’

Chief Suruí, leader of the Paiter-Suruí tribe, emerges from his concrete house into a blaring sunny morning and sits on a bench under the shady, palm-thatched roof of his tribe’s ceremonial living area.

He is holding a basket of worms, called gongo, which he pops into his mouth like peanuts. Damon, the little white dog that follows him everywhere, sits by the chief’s feet.

Suruí is famous, in Brazil and beyond, for his political activism, and considered a hero by his people for appealing to government leaders for support that has helped the tribe survive. He is often whipsawed by the demands of his position—one day speaking to the United Nations in New York City, the next living a modest life in his village of tin-roofed houses, about 800 miles south of Manaus, in the state of Rondônia.

Suruí connected with a team of Paris-based lawyers last year to file the complaint against Bolsonaro because, he said, he believes the president has put his allies in positions of power, allowing them to run agencies that have steamrolled Indigenous rights and weakened environmental protections.

“The government has an important role to guarantee the future,” he said. “If the government doesn’t accept this duty, it’s an ecocide.”

Suruí is not just angry at Bolsonaro who, he said, has opened the door to more agribusiness, mining and logging on public and Indigenous land. He is also angry with the corporations that are taking advantage of Bolsonaro’s leniency and funding lobbying groups that are pushing laws to dismantle Indigenous and environmental protections.

“Illegal things happen because there’s a big market. Business gives us profit right away,” Suruí said. “People don’t think of the consequences.”

He said he hopes the international court, by making ecocide a crime, can step in, but he knows the court moves slowly.

“I know it will take a long time and I don’t have much hope,” he said. “But I know with this filing the world will learn how unhappy we are with Brazilian politics.”

Walking through the rainforest surrounding the village, he points out a huge tract of forest that was burned by loggers in 2019, in retaliation for the tribe’s resistance to their trespassing. Now coffee, manioc, cupuacu and cacao plants grow there.

“It’s possible to produce responsibly,” he said. “We don’t need to deforest another inch of the Amazon.”

‘The Dream of All Miners’

Odacir “Gringo” Leseux has gone to jail three times for mining illegally in the Amazon rainforest.

“They caught me with diamonds in my hands. The feds got me in my house,” he said, matter of factly. “But that was my job. I could feed my family. I bought that house.”

In a suede-brimmed hat, polo shirt and jean shorts, Leseux looks like someone who used to bet on greyhounds at a dog track in Miami. Like someone who relies on a little luck.

“Mining is an illusion,” he said. “You only make coins, but you talk about millions. That’s the dream of all miners. It’s all about dreams.”

Leseux is traveling along a road called the Transgarimpeira, or “Trans-miners,” that stretches west off the BR 163, about a 20-hour drive northeast of the Suruí territory. It’s familiar terrain for him: He has mined here for years and keeps a few of his things in a dormitorio near Boa Esperança, one of the mining settlements along the route.

Like thousands of small-scale miners—known as wildcat miners or garimpeiros—he has no plans to stop looking for gems in the rainforest.

Fabrizio Schwingle, a restaurant owner from the city of Cuiabá, several hundred miles to the south, is looking for gold near Boa Esperança, where he spends most of the year living under a tarp in a makeshift camp in the jungle. A generator hums from the edge of the forest, running a sluicing machine that looks like a Steampunk prop. Chickens peck around amid the trash and empty plastic bottles that cover the forest floor. One hen has left her eggs next to a generator that died months ago.

“I have a churrascaria in Cuiabá,” Schwingle said, sweat dripping off his face. “But gold is an addiction.”

That addiction is enabled by growing global demand and soaring prices for gold.

In the last several years, a gold rush in the Amazon has led to more incursions on tribal lands and more rainforest destruction. One recent study found that about 30 percent of the gold mined in Brazil is extracted illegally, and from the beginning of 2019 to the end of 2020, new mining areas destroyed more than 80 square miles of forest. A bill introduced by Bolsonaro would allow more mining on Indigenous land, and if it passes the Brazilian congress, researchers estimate deforestation could rise another 20 percent.

“Bolsonaro’s father was a wildcat miner,” said Raoni Rajão, a researcher with the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais and a co-author of the study. “He has this perception that wildcat miners are entrepreneurs and heroes.”

Mining doesn’t drive the same high levels of deforestation as soy or cattle, Rajão noted, but it poisons water and is leading to escalating conflicts with Indigenous tribes. “You have violence. The suffering of the Indigenous population,” he said. “That’s the most concerning issue.”

The Transgarimpeira passes clusters of settlements known as currutela and small towns that look like Amazonian “Deadwoods.” They have names that promise fortune, like the Jardim do Ouro, or Garden of Gold, and they offer all the usual distractions and necessities: boarding houses, bars with pool tables, churches and “black beetles”—one-room, improvised brothels wrapped in black plastic sheeting. Prostitutes are paid in gold.

“I know one lady who sold her house in Manaus and goes for 20 days to one currutela, then on to the next,” Leseux said.

Above his open pit mine at Boa Esperança, José Nascimento, who has been mining the Amazon for decades, walks along a tall dirt embankment, peering down at two young employees who are spraying high-pressure streams of water onto slopes of dirt. The water goes into a trough and is pushed by the water pressure onto a ramp, where the solids drop into a rustic catchment system. Later, using mercury and a rag, Nascimento will squeeze these solids, pressing out tiny amounts of gold and mercury. In a very good week, he will end up with about 200 grams of gold.

“When we produce some gold, I get so happy,” he said, looking up from the brim of a baseball hat bearing the words “Amazon Gold.” “Sometimes I work one or two years—nothing. Then boom!”

Nascimento is optimistic about the future. “I still have virgin forest back there,” he said, pointing to the chunk of the rainforest that he’s arranged with the landowner to cut down and mine. “That area? It’s all gold.”

Asked if he worries that mining is destroying the rainforest, he brushes it off. “My impact is low compared to the wealth I produce,” he said. “Do you know how much a farmer destroys? Five thousand acres.”

“This will be very different,” he said, because the trees will grow back.

His fellow miner, Leseux, was a farmer for a little while, but was lured into gold and diamonds in the late 1980s. Sometimes he wishes he’d stuck with farming, Leseux said.

“I was in Mato Grosso, planting soy and rice. I came to visit a mine in Juina and never left,” he said, referring to a city in that state. “I know if I had never left grains, I’d be a rich man today.”

But the thrill of illicit mining is now in his blood. Soon, he’ll be leaving for the state of Roraima, farther north. He’s heard rumors of big paydirt there.

“It’s a huge adrenaline high,” he said. “All the time you’re running from the police. But then you get far into the forest and you’re free.”

A Territory Under Threat

On a cloudy October morning, Chief Juarez Munduruku gathered with his family at a table in his palm-thatched house. One of his grandchildren fed crackers to a green parrot. A tamarin looked down from a water tower. A macaw swooped in circles around the village, called Sawré Muybu, which is about 300 miles south of Santarem.

The chief looked worried.

Through a YouTube channel that Amazonian tribes subscribe to for information about political developments and events in Indigenous lands, the chief had learned that members of another tribe, the Kaingang, had been killed in a territory to the south. The killings, he said, stemmed from a disagreement between Kaingang members over leasing some of their lands to soy farmers. Demand for new land to grow soy has become so great that agribusinesses are seeking to expand into Indigenous territories, creating conflicts within some tribes over allowing the leases and distribution of the proceeds.

The chief blames these rising tensions squarely on Bolsonaro, who has made it clear that developing more of the Amazon goes hand-in-hand with removing protections for Indigenous lands.

“Land leasing is something that originates with the government,” he says. “Sooner or later it will be problematic. It will divide the tribes. Division is not good.”

Asked if his own tribe is in agreement over whether to allow development in its lands, he hesitates for a beat: “I think so.”

The Amazon is home to more than 400 Indigenous groups, 80 of which are “uncontacted” and live in voluntary isolation from the modern world. But the Munduruku tribe, like the Paiter-Suruí and others, live a kind of hybridized life, close to nature and the rainforest, but entwined with a modern economy.

The pressures from the outside world have meant they have been forced to engage with it to defend their land and rights. Like Chief Suruí, Munduruku has become a prominent political force, drawn into activism because of mounting illegal incursions on his tribe’s land.

In Sawré Muybu, RoseAnnie Munduruku lives with her four children and grandchild in a modest house, where hammocks swing above concrete and dirt floors and a television plays cartoons with the sound off. She’s known as the village cook, able to deftly transform local fish, including piranha, into nightly spreads.

Her children go to the village school, housed in a rusty-roofed shack where the students have drawn lessons and characters on the walls. Some of them are pro-Indigenous graffiti, conveying the anger that has riled this and other Indigenous communities since Bolsonaro took office.

Over the course of the summer, an unprecedented wave of Indigenous protests swept across the country, mostly on Brasilia’s “Monumental Axis”—akin to the National Mall in Washington, D.C.—where thousands of people marched against Bolsonaro’s proposals or those supported by industries allied with the president.

RoseAnnie Munduruku rarely leaves the village, but this past August, she traveled by bus—two days and two nights—to attend a protest in Brasilia against one of Bolsonaro’s proposals that would weaken Indigenous rights to their lands.

“What I do best is cook,” the 48-year-old grandmother said defiantly as she collected dishes from the dinner table. “I wasn’t there to cook.”

A Risky Job

On a wall inside the offices of an Indigenous rights advocacy group called Kanindé, is a giant image: a black-and-white photo of a 4-year-old girl wearing a headdress of feathers, her smiling face turned up toward the sun.

Twenty years after the photo of her was taken, Txai Suruí sits in the room where it hangs, tapping away at her laptop. A member of the Paiter-Suruí tribe, she is now a climate and Indigenous rights advocate, one member of an upwelling of youth activists across the Amazon.

“If you look at a map, you see where there’s forest is where the Indigenous people are,” Suruí said. “The rest is destroyed.”

Being an activist is a risky job in Brazil. A recent report found that 20 Indigenous and environmental activists were killed here last year. The Kaninde employees are well aware of this. The modest office is wired with security cameras and guarded with metal bars.

Ivaneide Bandeira, who is Suruí’s boss and founded the group in 1991, said she receives threats from people she believes are tied to local politicians and industry groups. “I can’t go outside by myself,” she said.

In October, Suruí traveled to Glasgow for the United Nations Climate Change Conference known as COP26. There she met with global leaders, spoke on a panel about the role of Indigenous youth in tackling the climate crisis, and marched in the street with a sign that read “Stop Bolsonaro for the Future of the Planet.”

The presence of Amazonian Indigenous groups in climate talks isn’t new, but research behind their role in forestalling the climate crisis is growing. In the weeks leading up to COP26, advocacy groups released a new report saying that Indigenous peoples were not only the best stewards of forest conservation—as research has shown before—but that this stewardship translated to significant and specific amounts of carbon storage.

One study found that Indigenous lands and community territory contain roughly 250 billion metric tons of carbon across 24 tropical countries, but also noted that these communities only have legal rights to less than half of that area. That, the authors say, weakens Indigenous communities’ ability to protect the land and the carbon stored in its forests and soils.

Another study found that Indigenous communities in 64 countries stored more than 290,000 million metric tons of carbon, roughly 33 times global energy emissions in 2017. In the Amazon, a more recent study found, 94 percent of Indigenous lands were carbon sinks compared to non-Indigenous lands in the Amazon, which were net carbon emitters.

“The communities in these forests are completely connected to nature,” she said. “They’re the solution.”

‘They Lie’

Chief Munduruku rides down the Tapajos river in a jon boat, through the valley his ancestors have lived in for hundreds of years. A cluster of machetes rests in the boat’s bow. The chief, his wife and a few relatives sit in the back, drinking coffee from a thermos.

They make outings like this every once in a while, to check on the tribe’s lands, which occupy thousands of acres on either side of the river, a major tributary of the Amazon.

Over the last 10 years or so, more miners and loggers have crept in, setting up camps and digging for gold or gems, or coming with chainsaws, taking a mahogany tree here, an ipe tree there, eating into the rainforest like termites. The river, unpolluted seven or eight years ago, is now filled with silt, churned up by barges dredging the river bottom for gold. The water feels and looks like milky tea.

The land is so vast and thickly vegetated that the Munduruku people don’t have enough eyes to patrol it. Government agencies don’t have the bodies either—or the will—and under Bolsonaro, the monitoring has become yet more anemic.

“The destruction—we know it’s going on everywhere,” the chief said, before the excursion. “Deforestation is coming from one side, fire from the other.”

The boat arrives at the river’s edge. A man approaches, explaining that he’s an evangelical Christian and there to gather supplies from a camp about 30 miles (50 kilometers) away. He apologizes to the chief for being on his land. Later, the group sees the contents of the man’s pick-up truck: a chainsaw, engine oil, diesel and salt, used to preserve food during long stays in the jungle. At the base of some trees nearby is a stack of palm hearts—harvested illegally.

The chief is a mild-mannered man, with close-cropped salt-and-pepper hair that suggests business. When he laughs, which he does easily, a fan of wrinkles spreads at the corner of his eyes. But as his boat pulls away from the landing, his normally placid face turns cloudy. He bites down on a macaw feather-turned-toothpick that twitches angrily in his teeth.

“They’re stealing,” he said.

In the past couple of years, the chief and his fellow tribal leaders have found bulldozers and trucks in spots up and down the river. The intruders were clearly trespassing on tribal land, but the chief simply asked them to leave. The next time he finds them, he said, he’s going to set their equipment on fire.

“They say things. They say they’re not going to come back,” Chief Munduruku said. “They lie.”

One of the complaints filed with the international court says that there have been 41 recent incursions into Munduruku lands, which have been “subject to an evident increase in violations by wildcat miners, palm-hear(t) gatherers and loggers, encouraged by President Jair Bolsonaro.” The complaint also notes that the headquarters of a Munduruku women’s association was torched earlier this year.

The Munduruku are still awaiting a formal demarcation of the boundaries of their territory, which would confer stronger protections on their land. When they started the process of getting the demarcation seven years ago, the chief and other members of the tribe started getting threats from miners and loggers allied with local politicians.

“Just down from the village, five guys came looking for me,” Chief Munduruku recalled. “The guys came very close to me. One turned as they were leaving and took a picture. Their behavior was hit-men behavior. I took it as a threat. I didn’t sleep after that.”

He said he has been followed in Itaituba, the nearest big city, and as he went to the landing at Burbure, where boats depart for Sawré Muybu.

There, gold barges sit at the river’s edge, waiting for repairs amid vultures and garbage, as techno music blares into the jungle from a nearby bar. The miners in Burbure glare at the Munduruku, who always travel with at least two other tribe members for safety.

“If I was scared, I couldn’t be in this fight,” the chief said. “I’m fighting for what’s mine. We’re not trying to steal.

Munduruku was appointed chief in 1999 and is now in his early 60s. He’s the father of eight; grandfather of 22. Like Suruí, he spends much of his time traveling, appealing to corporate and government leaders in Brazil and beyond to stop the destruction of his tribe’s swath of the rainforest.

“I miss my family a lot. My grandkids,” he said, talking about his travels. “The sounds of the howler monkeys in the morning, the birds. I get truly homesick for my people. The wildlife surrounding the tribe—the tapirs, hogs, paca. We see things we don’t even know what they are. All this is the Amazon for me.”

Loggers or miners who cut the forest, either clearing it wholesale or a few trees at a time, and farmers who “clean” it with flames, often insist that the trees will grow back. Bolsonaro makes the same argument: The forest is renewable and will bounce back from what his administration calls “economic utilization.”

But science says otherwise. The towering hardwoods—mahogany, ipe and kapok—will take centuries to reach their full height. One square yard of rainforest, might contain seven or eight tree species, millions of microbes, countless insect and animal species that depend on a network of interactions with the vegetation, rainfall and soil that has evolved over millions of years.

It is infinitely complex and interconnected.

“If it’s deforested, the forest will grow back again,” the chief said. “But not like it was.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.