Surprising source of lead poisoning in Amazon

Inside the simple wood-frame house, a 6-year-old boy plays with a piece of malleable metal, biting it as his younger sister watches. In the background, piled against the wall, are two long strips of the metal – lead sheathing from an electrical cable that the family sold for scrap.

Lead seems like an odd thing to find in an Achuar village deep in the Peruvian Amazon. But the metal is valuable here, since it is easily molded to make perfect weights for fishing lines and nets.

That convenience comes at a cost. Three out of every four children in communities in the Corrientes River basin have blood lead levels higher than those considered excessive under U.S. health guidelines.

The lead strips found inside the homes solved a mystery that had long puzzled researchers.

Scientists had expected to find that water polluted by oil drilling upriver was responsible for the villagers’ high lead levels. But to their shock, they discovered that children and teens were fashioning homemade fishing sinkers from scrap lead with their teeth.

“The results were really unexpected,” said Peruvian researcher Cynthia Anticona, who conducted the study as part of her doctoral research in public health at Umeå University in Sweden.

“When we did the fieldwork, I no longer had any doubt. I saw how 5- and 6-year-olds chewed pieces of lead,” she said. “We’d been looking everywhere, when the answer was right there.”

Children exposed to lead, which can damage developing brains, have lower IQs and behavioral problems, including aggressiveness. Many experts say there is no safe level of lead for children.

Older children and teens in the villages have the highest levels, especially boys, who fish more often than girls.

Such high lead levels in adolescents are surprising, according to Bruce Lanphear, a professor at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, who is a leading expert on effects of lead exposure on children.

“This would be the equivalent of adolescents working in a lead-related hobby or workplace,” he said. “These are substantial exposures.”

Toddlers who crawl on the ground and put objects in their mouths are usually at the greatest risk of exposure, he said. Lead levels usually drop in adolescents, although by then the damage to their developing nervous systems has already been done. Little is known about the effects of exposure that occurs when a child is older, Lanphear said.

If the young fishermen replaced the lead with non-toxic sinkers, their blood lead levels should show a notable decline within a few months, he said.

But so far, nothing has changed in these Amazonian villages, which are so remote that it takes several days by boat to reach the nearest city. Up to 40 families, with an average of three or four children each, live in wooden houses with palm-thatch roofs. They have little access to health care.

Unexpected source

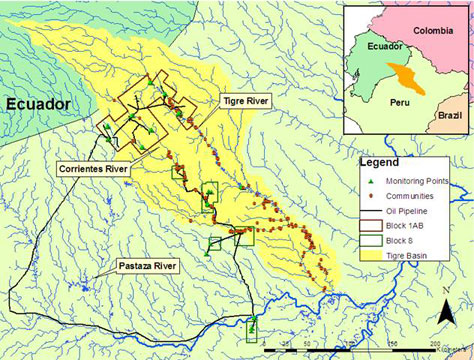

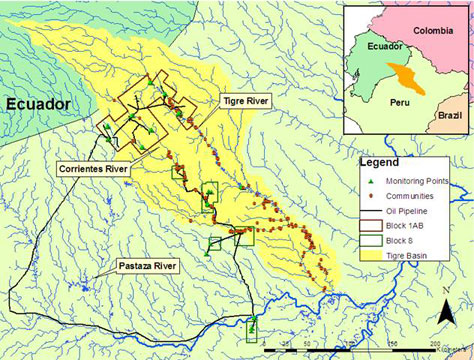

When Anticona and her adviser, Miguel San Sebastián, who had studied the health impacts of oil pollution on indigenous communities in Ecuador in the 1990s, began their study in these villages, they were not thinking of fishing sinkers.

Several earlier studies had found lead and cadmium in water and in the blood of people along the Corrientes River, and a report published in 2006 by a Peruvian non-profit organization pointed to oil operations as the likely source of pollution in Achuar communities. In January, the Peruvian government fined Argentina-based Pluspetrol $11 million for pollution.

Several earlier studies had found lead and cadmium in water and in the blood of people along the Corrientes River, and a report published in 2006 by a Peruvian non-profit organization pointed to oil operations as the likely source of pollution in Achuar communities. In January, the Peruvian government fined Argentina-based Pluspetrol $11 million for pollution.

Anticona and San Sebastián had thought their investigation into sources of the lead would lead them to the oil fields.

In 2009, they sampled water, soil and blood in two Achuar villages near oil fields that have operated for four decades, first under Peru’s state-run company and more recently under Pluspetrol. A Kichwa village on a tributary with no wells upstream served as an unexposed population for comparison.

The researchers expected to find higher blood lead levels in the communities near the oil operations and no notable levels in the other village. To their surprise, they found the lead levels were similar. Water and soil samples also showed no significant amounts of lead, indicating that people were not ingesting it from the environment.

Indigenous leaders questioned the accuracy of the analysis.

At first, Anticona said, “We had doubts, too.”

Looking beyond the oil wells, however, she found a clue in a study from Micronesia of lead in villagers who melted batteries to make fishing weights. Anticona returned to Peru with a redesigned study that included observing everyday activities in households where people had some of the highest blood lead levels.

It took her several months to convince indigenous leaders and local health authorities that even if the oil operations were not to blame, further study was needed to solve the public health problem.

Anticona expanded the study to six communities, including the original three, and enlisted the help of Michael Weitzman, an expert on lead exposure from New York University, who was doing unrelated work in the Peruvian Amazon at the time. In a remote, roadless area without electricity, Anticona needed generators and portable refrigerators to keep samples cold, and spent hours hiking through jungle to sample cassava and other crops in families’ fields.

In focus groups, residents described plomito, which are strips of lead that they broke apart for sinkers, often biting the pieces to shape them and sometimes heating them over an indoor fire, releasing – and inhaling – lead vapor.

She learned that people scavenged pieces of electrical cable from oil camp waste dumps, stripped the lead sheathing, sold the copper cable for scrap and stored the lead at home to make weights. Blood lead levels were higher in communities closer to the camps, where scrap lead was more readily available.

Overall, less than 22 percent of children in the villages had blood lead levels under 5 micrograms per deciliter, which is the health guideline set last year by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 27 percent had levels at least double that amount.

Kids under 6 who played with scrap lead had an increased risk of high levels. So did youngsters between ages 7 and 17 who fished at least three times a week and chewed lead to fashion sinkers.

Results greeted with hostility

When people saw where Anticona’s research was heading, they became reluctant to provide information and some indigenous leaders became hostile.

“No one likes to be told that they’re doing something untoward to themselves and their children,” Weitzman said.

Instead, they wanted to blame the oil companies.

“It didn’t favor us,” Andrés Sandi, president of the Federation of Native Communities of the Corrientes River said of the study. In a telephone interview, he called it a waste of money from a health program established after protests in 2006, when Achuar people near the oil fields shut down the company’s operations to exert pressure for a pollution cleanup.

San Sebastián said the study results do not undermine arguments about pollution.

“We have tried to clarify that there are two types of problems,” he said. “One is the lead, and the other is the possible health effects of the environmental contamination.”

Pluspetrol spokeswoman Claudia Fontenoy said its refuse dumps do not currently contain lead-bearing waste such as batteries or electrical cables, and the company plans to eliminate the dumps altogether by 2014.

Anticona and her colleagues last December recommended an education program, non-toxic fishing sinkers and closure of the dumps. But because of turnover of public health officials and resistance from some communities, the recommendations have languished.

“It has been a great frustration for me,” she said, “that so far, nothing has been done.”

Lead seems like an odd thing to find in an Achuar village deep in the Peruvian Amazon. But the metal is valuable here, since it is easily molded to make perfect weights for fishing lines and nets.

That convenience comes at a cost. Three out of every four children in communities in the Corrientes River basin have blood lead levels higher than those considered excessive under U.S. health guidelines.

The lead strips found inside the homes solved a mystery that had long puzzled researchers.

Scientists had expected to find that water polluted by oil drilling upriver was responsible for the villagers’ high lead levels. But to their shock, they discovered that children and teens were fashioning homemade fishing sinkers from scrap lead with their teeth.

“The results were really unexpected,” said Peruvian researcher Cynthia Anticona, who conducted the study as part of her doctoral research in public health at Umeå University in Sweden.

“When we did the fieldwork, I no longer had any doubt. I saw how 5- and 6-year-olds chewed pieces of lead,” she said. “We’d been looking everywhere, when the answer was right there.”

Children exposed to lead, which can damage developing brains, have lower IQs and behavioral problems, including aggressiveness. Many experts say there is no safe level of lead for children.

Older children and teens in the villages have the highest levels, especially boys, who fish more often than girls.

Such high lead levels in adolescents are surprising, according to Bruce Lanphear, a professor at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, who is a leading expert on effects of lead exposure on children.

“This would be the equivalent of adolescents working in a lead-related hobby or workplace,” he said. “These are substantial exposures.”

Toddlers who crawl on the ground and put objects in their mouths are usually at the greatest risk of exposure, he said. Lead levels usually drop in adolescents, although by then the damage to their developing nervous systems has already been done. Little is known about the effects of exposure that occurs when a child is older, Lanphear said.

If the young fishermen replaced the lead with non-toxic sinkers, their blood lead levels should show a notable decline within a few months, he said.

But so far, nothing has changed in these Amazonian villages, which are so remote that it takes several days by boat to reach the nearest city. Up to 40 families, with an average of three or four children each, live in wooden houses with palm-thatch roofs. They have little access to health care.

Unexpected source

When Anticona and her adviser, Miguel San Sebastián, who had studied the health impacts of oil pollution on indigenous communities in Ecuador in the 1990s, began their study in these villages, they were not thinking of fishing sinkers.

Several earlier studies had found lead and cadmium in water and in the blood of people along the Corrientes River, and a report published in 2006 by a Peruvian non-profit organization pointed to oil operations as the likely source of pollution in Achuar communities. In January, the Peruvian government fined Argentina-based Pluspetrol $11 million for pollution.

Several earlier studies had found lead and cadmium in water and in the blood of people along the Corrientes River, and a report published in 2006 by a Peruvian non-profit organization pointed to oil operations as the likely source of pollution in Achuar communities. In January, the Peruvian government fined Argentina-based Pluspetrol $11 million for pollution.Anticona and San Sebastián had thought their investigation into sources of the lead would lead them to the oil fields.

In 2009, they sampled water, soil and blood in two Achuar villages near oil fields that have operated for four decades, first under Peru’s state-run company and more recently under Pluspetrol. A Kichwa village on a tributary with no wells upstream served as an unexposed population for comparison.

The researchers expected to find higher blood lead levels in the communities near the oil operations and no notable levels in the other village. To their surprise, they found the lead levels were similar. Water and soil samples also showed no significant amounts of lead, indicating that people were not ingesting it from the environment.

Indigenous leaders questioned the accuracy of the analysis.

At first, Anticona said, “We had doubts, too.”

Looking beyond the oil wells, however, she found a clue in a study from Micronesia of lead in villagers who melted batteries to make fishing weights. Anticona returned to Peru with a redesigned study that included observing everyday activities in households where people had some of the highest blood lead levels.

It took her several months to convince indigenous leaders and local health authorities that even if the oil operations were not to blame, further study was needed to solve the public health problem.

Anticona expanded the study to six communities, including the original three, and enlisted the help of Michael Weitzman, an expert on lead exposure from New York University, who was doing unrelated work in the Peruvian Amazon at the time. In a remote, roadless area without electricity, Anticona needed generators and portable refrigerators to keep samples cold, and spent hours hiking through jungle to sample cassava and other crops in families’ fields.

In focus groups, residents described plomito, which are strips of lead that they broke apart for sinkers, often biting the pieces to shape them and sometimes heating them over an indoor fire, releasing – and inhaling – lead vapor.

She learned that people scavenged pieces of electrical cable from oil camp waste dumps, stripped the lead sheathing, sold the copper cable for scrap and stored the lead at home to make weights. Blood lead levels were higher in communities closer to the camps, where scrap lead was more readily available.

Overall, less than 22 percent of children in the villages had blood lead levels under 5 micrograms per deciliter, which is the health guideline set last year by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 27 percent had levels at least double that amount.

Kids under 6 who played with scrap lead had an increased risk of high levels. So did youngsters between ages 7 and 17 who fished at least three times a week and chewed lead to fashion sinkers.

Results greeted with hostility

When people saw where Anticona’s research was heading, they became reluctant to provide information and some indigenous leaders became hostile.

“No one likes to be told that they’re doing something untoward to themselves and their children,” Weitzman said.

Instead, they wanted to blame the oil companies.

“It didn’t favor us,” Andrés Sandi, president of the Federation of Native Communities of the Corrientes River said of the study. In a telephone interview, he called it a waste of money from a health program established after protests in 2006, when Achuar people near the oil fields shut down the company’s operations to exert pressure for a pollution cleanup.

San Sebastián said the study results do not undermine arguments about pollution.

“We have tried to clarify that there are two types of problems,” he said. “One is the lead, and the other is the possible health effects of the environmental contamination.”

Pluspetrol spokeswoman Claudia Fontenoy said its refuse dumps do not currently contain lead-bearing waste such as batteries or electrical cables, and the company plans to eliminate the dumps altogether by 2014.

Anticona and her colleagues last December recommended an education program, non-toxic fishing sinkers and closure of the dumps. But because of turnover of public health officials and resistance from some communities, the recommendations have languished.

“It has been a great frustration for me,” she said, “that so far, nothing has been done.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.