Supply and demand: World oil markets under pressure

(By CBC News Online) - Better plan on getting by without that SUV. In fact, you might want to go cold turkey and learn how to use public transit sooner rather than later. The world is running out of oil – if you subscribe to the Hubbert peak theory.

(By CBC News Online) - Better plan on getting by without that SUV. In fact, you might want to go cold turkey and learn how to use public transit sooner rather than later. The world is running out of oil – if you subscribe to the Hubbert peak theory. It’s named for Dr. M. King Hubbert, a geophysicist who predicted in 1956 that U.S. oil production would peak in 1970 and start steadily declining until reserves ran out – sometime late in the 21st century.

Turned out he was right. American production has been on the downswing since 1970, just before OPEC burst onto the scene as the dominant force in determining the price of a commodity on which the Western world depends.

Hubbert worked for Shell Oil and later for the U.S. Geological Survey. He died in 1989 – six years before his predicted peak for world oil production.

While few scientists believe that world production has already peaked, there are many who say we’re very close to it.

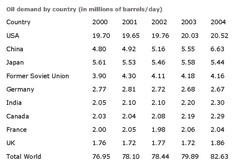

In 2002, the world used four times as much oil as was newly found. In the first quarter of 2005, world oil use was estimated at 82.63 million barrels per day.

The United States burns a quarter of that. Of the 20 million barrels a day that fuels the American economy, 25 per cent is burned up on the roads.

World demand for oil is expected to increase by 54 per cent in the first 25 years of the 21st century, according to the Energy Information Agency of the U.S. government. To meet that demand, the world’s oil-producing countries will have to pump out an additional 44 million barrels of oil each and every day by 2025.

Much of the growth in demand – about 40 per cent says the EIA #150 will come from Asia. Its daily oil fix is expected to double by 2025, thanks mainly to rapidly growing economies in China and India.

In 2004, China passed Japan as the world’s second-largest consumer of oil. It ate up an average of 6.63 million barrels of oil every day – about twice what it produces. Its oil imports doubled between 1999 and 2004.

China’s demand for oil is expected to continue to increase by five to seven per cent a year. If that happens, China will surpass the United States as the world’s largest consumer of oil by 2025.

Similarly, India’s oil needs are expected to grow by four to seven per cent a year. In 2004, it consumed two million barrels a day.

That can’t go on forever. The International Energy Agency – which gathers production information from producers around the world – expects the world to hit peak production between 2013 and 2037. After that, the agency predicts, production will fall by three per cent a year.

Hubbert’s old employer – the U.S. Geological Survey – says the peak is 50 years or more away. And it’s pointing to Canada as one of the top reasons for its optimism.

The USGS periodically releases its estimates of how much oil is still in the ground around the world. Saudi Arabia consistently tops that list. But two years ago, Canada moved from number 20, with about five billion barrels of recoverable oil, to second place – with an astonishing 180 billion barrels.

The USGS says Alberta’s tar sands is the reason. It argues it’s now economically viable to get at the vast reserves of oil there. The tar sands currently account for 26 per cent of Canada’s oil production, but by 2025 that figure could grow to 70 per cent.

Oil production from the tar sands is expected to double to two million barrels per day by 2010. That could increase to 10 million barrel per day by 2030.

Oil production from the tar sands is expected to double to two million barrels per day by 2010. That could increase to 10 million barrel per day by 2030. Saudi oil – extracted the old-fashioned way, through oil wells – costs just a few dollars a barrel to produce. In Alberta, the stuff from the oil sands can cost $20 a barrel or more to mine. And the process uses a lot more energy than pumping conventional oil.

Still, as the era of cheap oil fades, more eyes are turning toward Alberta. Increasingly, they’re Asian.

On April 13, 2005, Chinese oil producer CNOOC Limited bought a chunk of Canada’s oil sands industry by buying a $160-million stake in a company that’s been acquiring land for a project.

Meg Energy Corp. is planning on pumping 25,000 barrels of crude a day from the northern Alberta site by 2008. The investment is relatively small, but it’s expected to open the door to further involvement by CNOOC in the region.

A day later, came word that Enbridge and PetroChina International are working together to develop a $2.5-billion pipeline to supply Asia with crude oil from the oil sands.

The proposed Gateway Pipeline would stretch 1,160 kilometres from Edmonton to a port in British Columbia – likely Kitimat or Prince Rupert – where the oil would be shipped to various locations in Asia and California.

It takes time – several years – to get new projects on stream. The world’s oil producers have generally been able to meet demand. However, should demand spike – either through the needs of developing countries or a particularly harsh winter – there could be a shortage (even if we haven’t reached the peak of production).

The London-based Oil Depletion Analysis Centre recently released a study that predicted tight supplies through the rest of this decade, even if all of the new major oil recovery projects scheduled to come on stream over the next six years meet their targets. The only way to avoid it, the study said, is for demand to drop sharply.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.