Storms Will Be Stronger In A Warming World

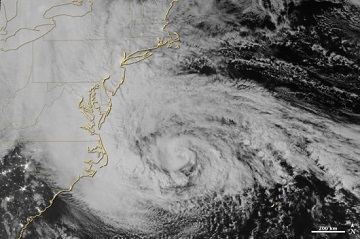

Few images are as beautiful and as terrifying as a satellite view of a hurricane about to make landfall. On October 29, 2012, the Suomi NPP satellite captured an ominous nighttime view of Sandy — an enormous hybrid storm that was part hurricane, part Nor’easter — churning off the coast of New Jersey.

Few images are as beautiful and as terrifying as a satellite view of a hurricane about to make landfall. On October 29, 2012, the Suomi NPP satellite captured an ominous nighttime view of Sandy — an enormous hybrid storm that was part hurricane, part Nor’easter — churning off the coast of New Jersey.The string of city lights that stretches from Washington to Boston was mostly gone, blanketed by thick, ghostly storm clouds. One of the most brightly lit cities in the world, New York, was little more than a faint smudge through Sandy’s clouds.

In a matter of hours, that smudge of light would go dark. Large swaths of Manhattan were under water. The Rockaways were on fire. Rooftops along the New Jersey shore became temporary islands for people escaping a wall of seawater that surged inland.

Hurricane Sandy knocked out power to much of lower Manhattan, New York.

Was Superstorm Sandy an expression of a “new normal” for our weather? Was it a storm pumped up by global warming?

“If you look at the unique set of circumstances in which Sandy emerged and you know something about meteorology and climate,” says Marshall Shepherd, director of the atmospheric sciences program at the University of Georgia, “it’s hard not to ask yourself these kinds of questions.”

Research meteorologist Marshall Shepherd.

Sandy is not the only recent storm to make people ask questions about climate change and weather. In 2010, an epic winter storm dubbed “Snowmageddon” dumped more than half a meter (2 feet) of snow across many parts of the U.S. East Coast. And in April 2011, tornadoes killed more than 364 Americans — the most ever in a month. The rash of twisters etched scars of destruction on the landscape so long and wide that they could be seen from space. The United States set records in 2011 and 2012 for the number of weather disasters that exceeded $1 billion in losses; most were storms.

Hackleburg High School in Alabama was destroyed by a tornado in April 2011.

All of these weather events occurred as the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere has been rising higher than it’s been for at least 100,000 years. Scientists are nearly certain that the buildup of carbon dioxide has already sparked changes in Earth’s atmosphere and ecosystems. The lowest layer of the atmosphere (the troposphere) has warmed markedly, especially at high latitudes. So have the world’s oceans. Heat waves and droughts have grown more likely and more extreme. Arctic ice is melting at a record pace, and the snowy landscapes of the far north have started melting earlier each year.

Given all the change that has already take place, it’s reasonable to wonder if climate change has affected storms as well. “After the tornadoes in 2011, I was flooded with calls from reporters,” says Anthony Del Genio, a climatologist at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS). “People wanted quick, definitive answers. The trouble is that’s not where the science is.”

Historically, research on tornadoes, hurricanes, and other types of storms has focused on short-term forecasting, not on understanding how storms are changing over time. Reliable, long-term records of storms are scarce, and the different reporting and observing methods have left many scientists and meteorologists feeling skeptical. But the study of storminess and climate has begun to mature, says Del Genio, and a consensus is emerging: for several types of storms, global warming may prime the atmosphere to produce fewer but stronger storms.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.