Small hydro projects -- renewable or ruinous?

Vancouver, Canada (GLOBE-Net) - With thousands of rivers and streams running through British Columbia, small hydro energy projects seem like a significant source of renewable energy. Although such projects have low environmental impacts compared to major hydro-electric dams, they face a significant level of opposition from the public.

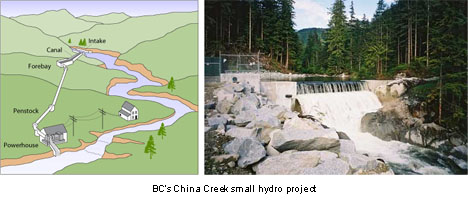

These small hydro projects known as run-of-the-river projects utilize the natural flow and elevation drop of a river to generate electricity. The projects are generally considered to be ‘green’, but the perceived environmental impacts and encroachment on First Nations land has drawn heated opposition from the public.

Recently a proposal to build eight new run-of-the-river projects on the Upper Pitt River in BC’s Pinecone Burke Provincial Park came under fire. Project, developer Run of River Power Ltd. submitted a proposal to change the park’s boundary in order to build a transmission line, stating the $350 million project wouldn’t compromise existing wilderness. The company called the project a clean, green energy proposal and said the damming would be quite small.

The company has applied under British Columbia’s park-boundary-adjustment policy to remove 70 hectares of land-21 hectares permanently-from the park to install a power line from the upper Pitt to Squamish.

Opposition to the project has been strong. Residents argue the project would harm the wetlands and surrounding area of the Park as well as a resurgent wolf population. B.C. Minister of Environment Barry Penner stated he will not approve the independent power project proposal for the Upper Pitt River, effectively killing the project.

While the Upper Pitt River was vehemently disputed, a second BC run-of-the-river project, albeit smaller in scale, is moving along quickly, with support from all stakeholders. As many as 5,000 homes could be powered by the Comox Valley’s first micro-hydro independent power project.

The K’omox First Nation is partnering with the Hupacasath First Nation to build a $15 million run-of-river power plant that will generate 6.5 megawatts when running at peak capacity.

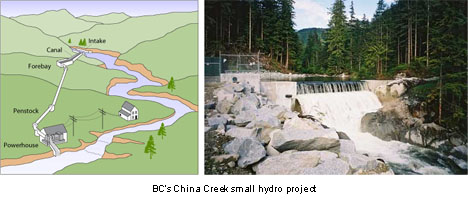

“This particular project is a nice, steady performer because it’s got pretty good capacity,” said Tom Jones, CEO of Tiickin Power, the power company that runs the Hupacasath First Nation power project on China Creek.

The project would consist of a small weir built in a canyon that diverts a portion of the river flow down a large pipe. The water drops about 160 metres in height over about 1.8 kilometres of pipe and is passed through a powerhouse that contains large turbines.

“It does provide opportunities [for jobs],” said K’omox band manager Melinda Knox. “It also provides an economic opportunity for us to partner with somebody who already has the knowledge and the skills for producing green energy that has the least amount of impact on the environment.”

Both projects utilize similar technology but have elicited very different responses from the public. Part of the problem may be the public perception of a hydroelectricity project as something very destructive.

Run-of-River projects are dramatically different in design, appearance and impact from conventional hydroelectric projects. Flooding the upper part of the river is not required as it doesn’t need a reservoir. As a result, people living at or near the river do not need to be relocated and natural habitats are preserved, reducing the environmental impact as compared to reservoirs.

There is also no alteration of downstream flows, since all diverted water is returned to the stream below the powerhouse. Instead of using dams, these small hydro projects use weirs. Although similar to a dam, a weir allows for a constant flow of water.

Developing a run-of-the-river project is fairly competitive to other energy sources depending on site electricity requirements and location. Maintenance fees are relatively small in comparison to other technologies. It only takes a small amount of flow or a drop as low as one metre to generate electricity with micro hydro.

The ecological impact of small-scale hydro is minimal; however the low-level environmental effects must be taken into consideration before construction begins. Stream water will be diverted away from a portion of the stream, and design elements such as fish ladders must be utilized to ensure there will be no negative impact on the local ecology.

Run-of-the-river hydro projects produce clean, zero-emission energy vital to British Columbia’s future – but it does not exempt them from potential negative impacts on the environment. The grim fate of the Upper Pitt River Project clearly illustrates that these projects, like any other, must be built in the proper location and the environmental impacts must be fully addressed, understood and mitigated through a thorough consultation process.

These small hydro projects known as run-of-the-river projects utilize the natural flow and elevation drop of a river to generate electricity. The projects are generally considered to be ‘green’, but the perceived environmental impacts and encroachment on First Nations land has drawn heated opposition from the public.

Recently a proposal to build eight new run-of-the-river projects on the Upper Pitt River in BC’s Pinecone Burke Provincial Park came under fire. Project, developer Run of River Power Ltd. submitted a proposal to change the park’s boundary in order to build a transmission line, stating the $350 million project wouldn’t compromise existing wilderness. The company called the project a clean, green energy proposal and said the damming would be quite small.

The company has applied under British Columbia’s park-boundary-adjustment policy to remove 70 hectares of land-21 hectares permanently-from the park to install a power line from the upper Pitt to Squamish.

Opposition to the project has been strong. Residents argue the project would harm the wetlands and surrounding area of the Park as well as a resurgent wolf population. B.C. Minister of Environment Barry Penner stated he will not approve the independent power project proposal for the Upper Pitt River, effectively killing the project.

While the Upper Pitt River was vehemently disputed, a second BC run-of-the-river project, albeit smaller in scale, is moving along quickly, with support from all stakeholders. As many as 5,000 homes could be powered by the Comox Valley’s first micro-hydro independent power project.

The K’omox First Nation is partnering with the Hupacasath First Nation to build a $15 million run-of-river power plant that will generate 6.5 megawatts when running at peak capacity.

“This particular project is a nice, steady performer because it’s got pretty good capacity,” said Tom Jones, CEO of Tiickin Power, the power company that runs the Hupacasath First Nation power project on China Creek.

The project would consist of a small weir built in a canyon that diverts a portion of the river flow down a large pipe. The water drops about 160 metres in height over about 1.8 kilometres of pipe and is passed through a powerhouse that contains large turbines.

“It does provide opportunities [for jobs],” said K’omox band manager Melinda Knox. “It also provides an economic opportunity for us to partner with somebody who already has the knowledge and the skills for producing green energy that has the least amount of impact on the environment.”

Both projects utilize similar technology but have elicited very different responses from the public. Part of the problem may be the public perception of a hydroelectricity project as something very destructive.

Run-of-River projects are dramatically different in design, appearance and impact from conventional hydroelectric projects. Flooding the upper part of the river is not required as it doesn’t need a reservoir. As a result, people living at or near the river do not need to be relocated and natural habitats are preserved, reducing the environmental impact as compared to reservoirs.

There is also no alteration of downstream flows, since all diverted water is returned to the stream below the powerhouse. Instead of using dams, these small hydro projects use weirs. Although similar to a dam, a weir allows for a constant flow of water.

Developing a run-of-the-river project is fairly competitive to other energy sources depending on site electricity requirements and location. Maintenance fees are relatively small in comparison to other technologies. It only takes a small amount of flow or a drop as low as one metre to generate electricity with micro hydro.

The ecological impact of small-scale hydro is minimal; however the low-level environmental effects must be taken into consideration before construction begins. Stream water will be diverted away from a portion of the stream, and design elements such as fish ladders must be utilized to ensure there will be no negative impact on the local ecology.

Run-of-the-river hydro projects produce clean, zero-emission energy vital to British Columbia’s future – but it does not exempt them from potential negative impacts on the environment. The grim fate of the Upper Pitt River Project clearly illustrates that these projects, like any other, must be built in the proper location and the environmental impacts must be fully addressed, understood and mitigated through a thorough consultation process.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.