Recycling: Are you doing it wrong?

Think you or your company knows how to recycle? Think again.

Sure, managing paper and glass and aluminum are pretty easy. But a new school of plastics, called bioplastics, has made recycling — arguably the lowest hanging fruit of ecologically conscious living — considerably more confusing.

“Bioplastic” is actually a confusing term that covers a range of materials that differ quite significantly from each other. Some bioplastics are exactly the same as conventional plastics used in packaging, except that all or a portion of the raw materials used to make them are derived from plants or plant byproducts rather than from hydrocarbons (one example is the Coca-Cola PlantBottle). Other bioplastics are made of very different polymers that lack the durability of conventional plastics but — and here’s the benefit — are designed to biodegrade at a rate commensurate with industrial composting systems.

It might feel counter-intuitive to place non-recyclable but compostable bioplastic packaging in a trash can, especially with some leafy eco-friendly label staring back at you, but it’s the right thing to do — unless you happen to live in a municipality that offers curbside composting.

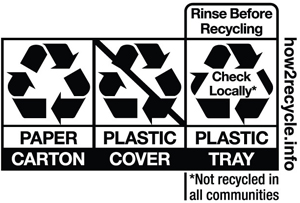

To reduce the confusion and keeping consumers and businesses from committing recycling sin on top of recycling sin, the Sustainable Packaging Coalition has launched How2Recycle, a labeling initiative that provides more nuanced recycling logos and helpful pointers for an increasingly confusing waste stream.

To reduce the confusion and keeping consumers and businesses from committing recycling sin on top of recycling sin, the Sustainable Packaging Coalition has launched How2Recycle, a labeling initiative that provides more nuanced recycling logos and helpful pointers for an increasingly confusing waste stream.“It’s pretty hard to be an educated consumer about bioplastics right now,” says Katherine O’Dea, director of innovation for GreenBlue, a Va.-based nonprofit that works with corporations to develop more sustainable packaging, chemicals and forest products. “There’s not that much communication about it.”

O’Dea will appear at the Sustainable Brands conference in San Diego next week, along with representatives from Sears, the chemical company BASF (which is investing heavily in bioplastics), packaging company Ecologic and consulting firm Chemrisk, on a panel addressing the rise of bioplastics.

Many cities support single-stream recycling, in which plastic, paper and other recyclable are placed in the same curbside container, but the systems used to separate materials later are often unable to sort non-recyclable bioplastics from the plastic stream (although many companies, including compostable bioplastics maker NatureWorks, are working to change this).

Compostable bioplastic sullies the recyclable plastic pool and lowers its value to recyclers. In fact, if a given pallet of recyclable plastic contains too much non-recyclable plastic, the whole thing might have to be land-filled. Conversely, non-compostable bioplastics placed in compost bins — say, by someone who sees the green leaf and PlantBottle branding on a Coca-Cola bottle and figures it will turn into humus after a few months in a compost heap — are filtered out of the compost stream and sent to landfills.

You might ask: Who cares? Bioplastic is still a very small portion of the waste stream. That is true today, but the market is posed for fast growth (one recent study points to a five-fold increase by 2016 ) so misdirected refuse could really start to screw up both recycling and composting streams. All major consumer brands are investing heavily in bioplastics R&D. Coca-Cola has joined a major effort with other brands as well as biotech firms in its quest to scale production of the PlantBottle bottle to include 100 percent bio-based feedstock.

Procter & Gamble and Kimberly-Clark are also hoping bioplastic packaging will help them achieve corporate sustainability goals. SC Johnson just introduced a line of compostable Ziploc sandwich, food storage and food scrap bags, which it sells online only, for now. The company would not reveal exactly what type of bioplastic the bags are made of or who manufactures them. But the products are certified as compostable by the Biodegradable Products Institute, which tests materials to ensure they will biodegrade fast enough to be placed in industrial composting systems.

Before ordering the bags — which are about 2.5 times more expensive than conventional Ziploc bags — you can look for a composter near your home. But it’s hard to imagine many consumers and businesses will strike off on their own to truck their food scraps and used bioplastic bags to a composter. More likely, these bags will sell well among the eco-conscious in cities that already support curbside composting, such as San Francisco, Boulder, Colo., and Salem, Ore.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.