New locks for Panama Canal near half-way point

The Panama Canal’s expansion is finally beginning to look like a channel that will float some of the biggest ships in the world by mid-2015.

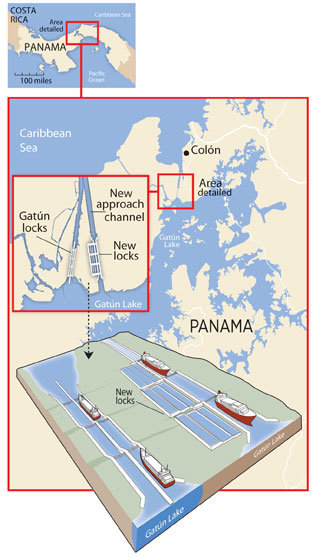

The Panama Canal’s expansion is finally beginning to look like a channel that will float some of the biggest ships in the world by mid-2015.About 42 percent of the work on the massive new locks has been completed, and it’s by far the most costly and complicated part of the $5.25 billion project to retrofit the nearly century-old canal with larger locks to lift and lower ships on both the Atlantic and Pacific sides of the isthmus.

The old locks will still be in service, but the new ones will allow the canal to handle so-called post-Panamax ships. The length of three football fields, such vessels are too long, too heavy and too wide to fit through the existing locks.

Most of the rest of the canal renovation, such as deepening and widening channels along the original route of the canal and construction of new access channels, is finished or nearly so. In early March, a milestone was reached when dredging of Culebra Cut, the narrowest part of the canal that straddles the Continental Divide, was completed.

But for Panama, which gets about $1 billion a year from the canal, the massive construction project needed to be done yesterday.

Maersk Line, the world’s largest container-shipping line, has stopped using the Panama Canal for its Asia service to U.S. East Coast ports. Next week, it plans to resume Asian sailings to the Eastern Seaboard through the Suez Canal.

Because the Suez can accommodate post-Panamax vessels, Maersk officials say it’s more cost-effective. Maersk has not said whether it will run its Asia service through the Panama Canal once the expansion is completed.

Jorge Quijano, chief executive of the Panama Canal Authority, said he expects the new locks will help Panama bring “back home” some of the services that have switched to the Suez.

Work on the expansion is about eight months behind schedule, mainly because the international consortium working on the locks didn’t initially get the concrete mix right.

“We wanted a mix that could be guaranteed for the next 100 years,” said Jorge de la Guardia, executive director of the PCA’s locks project management division. Heavy rain and a few strikes also have set the work back.

But a new canal visitor’s center overlooking the Atlantic construction site and Gatún Lake opened right on schedule — Aug. 15, 2012, the 98th anniversary of the opening of the canal.

‘GOLDEN ROUTE’

Long before anyone dreamed of a canal, this narrow isthmus in Panama was known as the “golden route” and was the pathway over which much of the gold from the New World was sent to Spain. Later, during the California gold rush, miners crossed the isthmus to board ships heading up to California.

Now the gold comes from ship crossings. A container ship pays as much as $400,000 to traverse the canal. On a recent day eight ships were stacked up in Gatún Lake ready to enter the Atlantic locks as workers poured concrete at the excavation site.

Fees for using the new locks are still being worked out, but it’s crucial that the canal authority get them right so the canal will be able to compete against U.S. West Coast ports and the Suez Canal — and to insure that shipping lines will continue to send smaller ships through the original locks.

Construction on the Atlantic side of the canal near the city of Colon is proceeding quicker than on the Pacific where the capital Panama City sits. But that’s because an old site where the Americans began work on a canal expansion in 1939 could be

That expansion was strategic. The United States, which controlled the 50-mile long canal until 1999, wanted to be able to move battleships between the Atlantic and Pacific and the ships were too large to make it through the locks.

The project was abandoned in 1942, however, after the Pearl Harbor attack as the United States devoted its full attention to the war effort. After the war, the U.S. had both Atlantic and Pacific fleets and never revived its plans for the larger locks.

The excavation sites became water-filled ditches full of fat alligators, big fish and even abandoned cars, said de la Guardia.

But on the Atlantic side, the old ditch and the site chosen for the new locks and access channel overlapped almost perfectly, giving engineers a head-start. On the Pacific side, the canal authority didn’t like the site excavated by the Americans and are constructing the new locks nearby on a site with a more solid basalt rock foundation.

That means the Atlantic side of the expansion could be finished by the end of 2014 or the beginning of 2015, allowing testing of the new locks and training to begin while work proceeds on the Pacific side, said de la Guardia.

“We can learn from the Atlantic side while the Pacific is still getting ready. It will be like going to school for the canal pilots and tugboat operators,” he said.

The canal authority also may allow some cruise ships that don’t make a complete transit through the canal to use the new locks before June 2015 and then turn around in Gatún Lake, which was created by damming the Chagres River in 1913 and is a critical part of the canal and its water supply.

Only a few hundred yards of dirt now separate the new access channel from Gatún Lake.

“It might not look like much but there is a plug between the lake and channel. It’s critical. If you lose the plug, you lose the lake,” de la Guardia said.

When the new locks are completed, the plug will be removed and a coffer dam that separates the locks from the Atlantic Ocean will be taken out, allowing flooding of the lock chambers to begin.

U.S. PORTS PREPARE

It isn’t just Panama that is racing against time to complete the canal expansion.

Ports up and down the East Coast of the United States also are trying to get ready so they can handle post-Panamax ships, which can carry as many as 13,000 containers — nearly three times more than the ships that now use the canal.

Already it’s clear that the canal expansion will change shipping patterns, because to maintain efficiencies, the big ships will call at fewer ports and unload more cargo, putting pressure on transportation and distribution links.

Only two Eastern U.S. ports — Norfolk, Va., and Baltimore — currently are deep enough to handle fully loaded post-Panamax vessels.

And in Central America and the Caribbean, only Freeport, Bahamas, the port of Caucedo in the Dominican Republic and the Panama City port are deep enough.

Meanwhile, New York Harbor has the depth but post-Panamax ships are too high to fit under the Bayonne Bridge. The Port Authority of New York & New Jersey hopes to start work to raise the bridge deck by mid-year.

PortMiami hopes to join the ranks of post-Panamax-ready ports by the time the canal expansion is complete. It already has the necessary approvals and funding to dredge its shipping channel to a depth of 50 to 52 feet.

The Army Corps of Engineers received bids for the $200 million PortMiami dredging project in January and is expected to award a contract in late April or early May, said PortMiami Director Bill Johnson.

Dredging could begin by June. If the two-year project goes off without a hitch, “we would expect to be open for post-Panamax traffic on schedule with completion of the canal expansion or slightly before,” Johnson said.

By summer, Johnson said, four super post-Panamax cranes that can pluck containers off the wide decks of the big ships are expected to arrive at Miami’s port.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.