Navy sonar 'did cause mass dolphin deaths'

The Royal Navy has been blamed for driving dozens of dolphins to an agonising death during anti-submarine war games.

A four-year investigation by scientists has ruled out every other cause for the UK’s largest stranding of common dolphins in shallows off the coast of Cornwall in 2008.

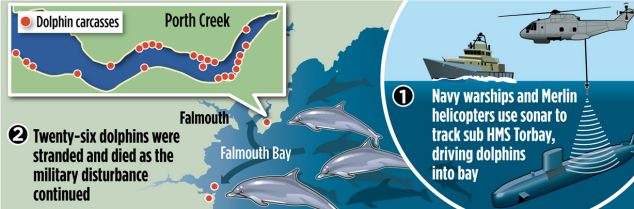

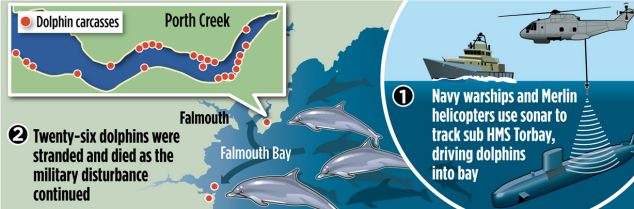

At the time, the area was hosting a week of ‘live fire’ war games involving 20 Royal Navy ships, helicopters and submarines – including the nuclear-powered sub HMS Torbay – as well as 11 foreign vessels.

And scientists now believe trials of anti-submarine warfare techniques, using a range of mid-frequency sonar devices in the water to detect hidden vessels, were the most likely cause of the dolphins’ deaths.

But despite calls from conservationists for military exercises now to be adapted to safeguard wildlife, the Navy has rejected the investigation’s findings.

Mid-frequency sonar, which transmits pulses of sound just beyond the range of human hearing, has been associated with past strandings of marine mammals.

The noise can cause hearing damage and scramble the dolphins’ sophisticated echo-location navigation system, driving them to shallow waters where they can suffer a slow and horrific death.

The scientists’ findings, published in the journal PLOS One, follow post-mortems on 26 short-beaked common dolphins found beached in Falmouth Bay on June 9, 2008.

Dr Paul Jepson of the Institute of Zoology, who led the research funded by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, said that a group of up to 60 dolphins swam into the bay three or four days before the stranding, probably to escape the disturbance caused by the anti-submarine sonar.

The expert said a second traumatic event, possibly from sonar or aircraft activity, on June 9 caused further agitation among the dolphin school, leading to the deaths of at least 26 that became stranded, mostly in an area called Porth Creek.

The Royal Navy has been blamed by scientists for causing dolphin deaths, but it denies the claims

‘Eyewitnesses described their behaviour as swimming continuously in tight circles, being vocal, fluke-slapping, leaning sideways, and often with one or more individuals attempting to strand,’ reported Dr Jepson.

A similar number of dolphins were saved by rescuers and herded back out to sea.

Dr Jepson said the dead dolphins – all but five were infants – had been in good health and ruled out other potential causes of death.

‘The mass stranding may have been a two-stage process where a large group of dolphins entered the bay, possibly to avoid a perceived acoustic threat,’ reported Dr Jepson.

‘After three or four days, a second disturbance occurred, causing them to strand en masse.

‘The international naval activities are the only established cause which cannot be eliminated and is ultimately considered the most probable, but not definitive, cause.’

But a Royal Navy spokesman said: ‘We do not agree with the conclusion of this report. Even its own extensive investigation has found no evidence to show naval activity was responsible.

‘Naval training has taken place in the area for over 60 years and active sonar has been in use throughout that time without any similar reported mass strandings. The Royal Navy is committed to taking all reasonable and practical measures to mitigate effects on marine animals.’

But conservation groups called for the Ministry of Defence to redesign exercises to safeguard wildlife.

‘This stranding is a game-changer and leads us to call for a re-evaluation of military activities,’ said Sarah Dolman, head of policy at Whale and Dolphin Conservation.

And Dr Jepson added: ‘Continual improvements in mitigation strategies by the military is probably the best way to limit future environmental impacts of naval activities.’

A four-year investigation by scientists has ruled out every other cause for the UK’s largest stranding of common dolphins in shallows off the coast of Cornwall in 2008.

At the time, the area was hosting a week of ‘live fire’ war games involving 20 Royal Navy ships, helicopters and submarines – including the nuclear-powered sub HMS Torbay – as well as 11 foreign vessels.

And scientists now believe trials of anti-submarine warfare techniques, using a range of mid-frequency sonar devices in the water to detect hidden vessels, were the most likely cause of the dolphins’ deaths.

But despite calls from conservationists for military exercises now to be adapted to safeguard wildlife, the Navy has rejected the investigation’s findings.

Mid-frequency sonar, which transmits pulses of sound just beyond the range of human hearing, has been associated with past strandings of marine mammals.

The noise can cause hearing damage and scramble the dolphins’ sophisticated echo-location navigation system, driving them to shallow waters where they can suffer a slow and horrific death.

The scientists’ findings, published in the journal PLOS One, follow post-mortems on 26 short-beaked common dolphins found beached in Falmouth Bay on June 9, 2008.

Dr Paul Jepson of the Institute of Zoology, who led the research funded by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, said that a group of up to 60 dolphins swam into the bay three or four days before the stranding, probably to escape the disturbance caused by the anti-submarine sonar.

The expert said a second traumatic event, possibly from sonar or aircraft activity, on June 9 caused further agitation among the dolphin school, leading to the deaths of at least 26 that became stranded, mostly in an area called Porth Creek.

The Royal Navy has been blamed by scientists for causing dolphin deaths, but it denies the claims

‘Eyewitnesses described their behaviour as swimming continuously in tight circles, being vocal, fluke-slapping, leaning sideways, and often with one or more individuals attempting to strand,’ reported Dr Jepson.

A similar number of dolphins were saved by rescuers and herded back out to sea.

Dr Jepson said the dead dolphins – all but five were infants – had been in good health and ruled out other potential causes of death.

‘The mass stranding may have been a two-stage process where a large group of dolphins entered the bay, possibly to avoid a perceived acoustic threat,’ reported Dr Jepson.

‘After three or four days, a second disturbance occurred, causing them to strand en masse.

‘The international naval activities are the only established cause which cannot be eliminated and is ultimately considered the most probable, but not definitive, cause.’

But a Royal Navy spokesman said: ‘We do not agree with the conclusion of this report. Even its own extensive investigation has found no evidence to show naval activity was responsible.

‘Naval training has taken place in the area for over 60 years and active sonar has been in use throughout that time without any similar reported mass strandings. The Royal Navy is committed to taking all reasonable and practical measures to mitigate effects on marine animals.’

But conservation groups called for the Ministry of Defence to redesign exercises to safeguard wildlife.

‘This stranding is a game-changer and leads us to call for a re-evaluation of military activities,’ said Sarah Dolman, head of policy at Whale and Dolphin Conservation.

And Dr Jepson added: ‘Continual improvements in mitigation strategies by the military is probably the best way to limit future environmental impacts of naval activities.’

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.