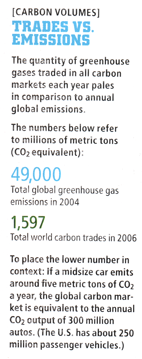

Making Carbon Markets Work - Carbon Trading 101 (extended version)

(By David G. Victor and Danny Cullenward) - Limiting climate change without damaging the world economy depends on stronger and smarter market signals to regulate carbon dioxide.

As Congress debates how to cut climate-warming emissions, insights drawn from the European carbon market can help. (Because of the timeliness of this issue, the editors of Scientific American decided to publish this article online in advance of its publication in the December issue.)

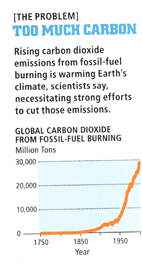

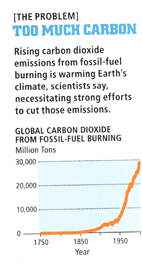

The odds are high that humans will warm Earth’s climate to worrisome levels during the coming century. Although fossil-fuel combustion has generated most of the buildup of climate-altering carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere, effective solutions will require more than just designing cleaner energy sources. Equally important will be establishing institutions and strategies—particularly markets, business regulations and government policies—that provide economies with incentives to apply innovative technologies and practices that reduce emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases.

The challenge is immense. Traditional fossil-fuel energy is so abundant and inexpensive that climate-friendly substitutes have little hope of acceptance without robust policy support. Meanwhile, for nearly two decades, negotiations on binding treaties that limit global emissions have struggled. But policy makers in Europe and other regions where public concern about climate change is strongest have already implemented significant initiatives to limit release of CO2. Lessons from these endeavors can help governments and world bodies fashion more effective strategies to protect the planet’s climate. Policy makers in the United States, which historically has produced more CO2 emissions than any other nation while doing relatively little to tame the flow, can in particular learn much about creating viable carbon-cutting markets by studying Europe’s recent experience. Based on these insights, we offer several concrete suggestions on how the U.S. should go about constructing an effective national climate policy.

A Global Approach

Until recently, nearly all policy debate about building institutions to protect Earth’s climate focused on the global level. Successful climate policy, thought analysts, activists and politicians, hinged on signing binding international treaties because the activities that cause climate change are worldwide in scope. Such an approach was needed because conventional wisdom assumed that if national governments merely acted alone, without global coordination, industries would simply relocate to where regulation was more lax.

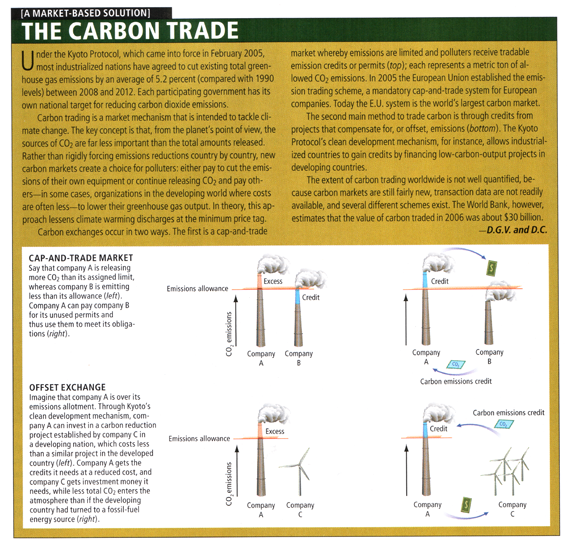

This globalist theory underlay the negotiation of the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which called for all countries to work in good faith to address the climate problem and created a new organization to oversee its implementation. That treaty spawned negotiations to produce more demanding agreements, leading to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. Under Kyoto, the industrialized states—including the U.S., the European Union (E.U.), Japan and Russia—agreed in principle to individually tailored obligations that, if implemented, would have cut industrial emissions on average about five percent below 1990 levels. But developing countries, which placed a higher priority on economic growth, refused to accept caps on their emissions. They argued that responsibility for greenhouse gas pollution fell squarely on the industrialized world.

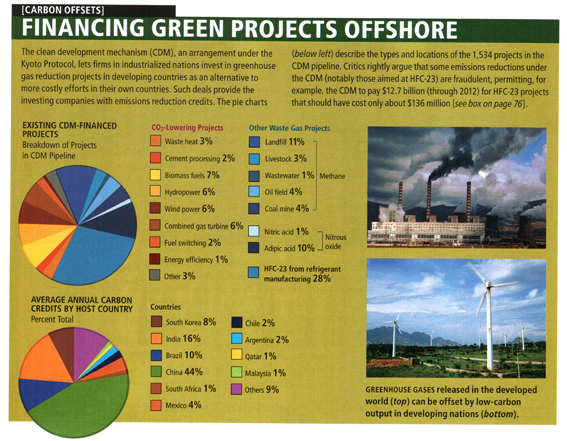

Clean Development Mechanism

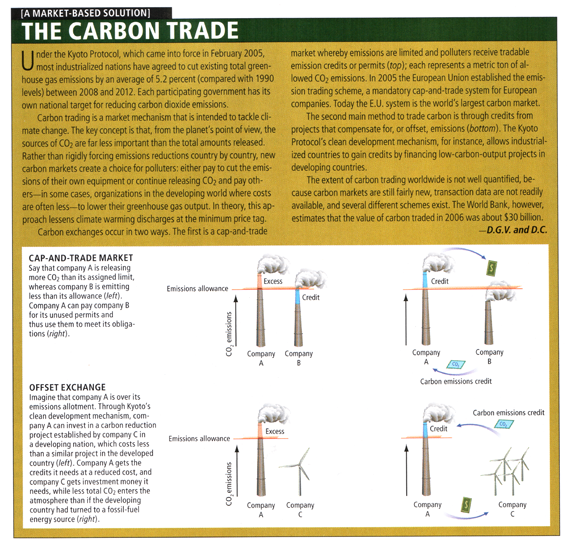

Without any practical way to force developing nations to control their emissions, the Kyoto signers instead reached a compromise known as the clean development mechanism. Under this scheme, investors could earn credits for projects that cut emissions in developing nations even though the host country faced no binding restriction on its output of these gases. A British firm that faces strict (and thus costly) limits on its emissions at home, for example, might invest to build wind turbines in China. The company would then accrue credits for the difference between the “baseline” emissions that would have been released had the Chinese burned coal to generate electricity and the essentially zero emissions discharged by the wind farm. China would gain foreign investment and energy infrastructure, while the British firm could meet its environmental obligations at lower cost because credits earned overseas are often less expensive than reducing emissions at home.

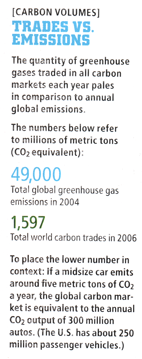

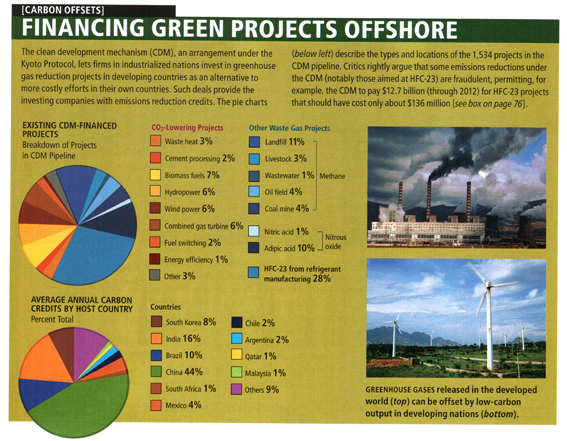

The market for clean development mechanism credits has since exploded in size, accounting for about a third of a percent of world’s greenhouse emissions and around $4.4 billion in annual value.

Making Agreements Stick

Although the Kyoto proceedings rapidly yielded an accord on paper, the real-world impact on global warming is small. Industrialized nations, where the obligations are most demanding, have implemented restrictions in an uneven fashion. Key countries—notably the U.S., but also Australia and Canada—have ignored the Kyoto strictures because they found them too costly or politically inconvenient. The U.S. economy, for instance, grew rapidly in the late 1990s, which raised its emissions output, making meeting the Kyoto targets even harder.

History shows that broad international treaties usually fail to find solutions to difficult problems. That is because these pacts normally reflect the interests of their least enthusiastic members and are often codified through weak commitments with easy escape clauses for governments that will not readily honor their agreements. Pushing tougher constraints on unwilling governments rarely works because reluctant nations can just remain aloof, as most developing countries and the U.S. have in the Kyoto process. (By contrast, the successful efforts to protect earth’s ozone layer were created with U.S. leadership. They also hinged on a special financing scheme to pay recalcitrant developing countries for the cost of instituting deep cuts in emissions, an option that is an essential part of addressing the climate change problem, but one that is much harder to carry out because the price tag is dramatically larger.)

In a few areas of international cooperation, such as the promotion of freer trade in goods and services, this dismal rule has not held because governments have tailored agreements to deliver tangible benefits to all key participants and have continued to work cooperatively over many decades. These instances present some guidance for creating more effective efforts to slow climate change. The World Trade Organization (WTO), for instance, began as a modest set of practical commitments between countries that were interested in expanding trade. As experience and confidence grew in the system, these states invited others to join. Together, they built stronger structures for monitoring and enforcement as well as more sophisticated agreements, which in turn made it easier to insist that every member comply with all commitments—even those that proved problematic. The WTO’s record is by no means perfect, but the relative success of its process is encouraging. And after 50 years of sustained institution building, it today enforces binding obligations concerning complex and divisive economic issues among most countries. In fact, the “organization” in WTO’s name emerged only in the 1990s, four decades after governments negotiated their first trade agreement. Back in the 1940s those same states had tried to create a strong global trade organization, but their efforts failed for reasons quite similar to those of today’s Kyoto process—demanding potential agreements collapsed when powerful countries found them inconvenient, leaving fledgling the institution powerless to impose compliance.

Evaluating Climate Policy

The extended, step-by-step process by which governments established the WTO is only just starting in the field of climate change. Effective policy is emerging from the exertions of a core group of countries that are most committed to regulating emissions. While nearly all of those countries have joined the Kyoto treaty, each has formulated a different strategy to control release of greenhouse gases, which stands in sharp contrast to the integrated, global approach that most analysts have advocated. The variety of plans does not surprise many scholars of international politics, for it reflects the fact that governments harbor deep uncertainties in the best way to manage emissions, and that they also vary widely in their capabilities and styles. Equally unsurprising is that most climate policies were grafted onto existing regulatory institutions. Japan, for example, set policy targets by relying on its traditional process of coordinating of key ministries (notably, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry). Norway, meanwhile, has pursued a different path, levying a carbon tax on its large oil and natural gas industry, a relatively straightforward task given that the Norwegian government owns most of the nation’s petroleum business.

The efforts to limit greenhouse gases within the E.U. are key because the withdrawal of the U.S. left the E.U. as the largest political entity following a comprehensive plan for regulation. Naturally, the Union tailored its program to match its existing regulatory capabilities. For the 55 percent of its total emissions produced by the building, transportation and other dispersed sectors that are difficult to monitor, the E.U. and its member states have extended a wide array of existing policies. These rules include, for instance, voluntary (soon to be binding) automotive fuel economy targets that were negotiated with the car makers. By next year, new vehicles sold in Europe are to achieve, on average, at least 41 miles a gallon for gasoline-fueled autos and at least 44 miles a gallon for diesel cars. (Automobiles in the U.S., by contrast, currently need only to reach 27.5 miles a gallon by 2010, and even fewer miles per gallon for trucks and sport utility vehicles. Actual U.S. average mileage is even lower due to various loopholes in the standards.)

The remaining E.U. sources—defined as producers of “industrial emissions,” including power plants—are fewer and larger, and thus easier to control. For these business segments, E.U. regulators designed an emissions trading scheme—also known as a cap-and-trade system—modeled on a successful U.S. acid rain-reduction program of the 1990s. Under this arrangement, every E.U. government allocates emission credits—each representing a ton of carbon dioxide gas per year—to its industrial plants. The companies then decide individually whether it is cheaper to reduce emissions, which would free up extra permits for sale, or buy permits from others on the open market. If emission cuts prove costly, demand for permits will rise and so will their prices. Alternatively, prices fall if low-cost technologies for lessening carbon dioxide release appear, or slow economic growth weakens the industries that emit CO2. By limiting the total number of permits, E.U. regulators fix pollution levels while the market sets the price.

Start-up Difficulties

Several teething problems have emerged in the short history of the E.U. carbon market. Countries have struggled when handing out the property to be traded—the critical starting point for any market. Many of the allocation plans that each government devises have arrived late and have been incomplete. In some cases they were laden with politically inspired manipulations designed to benefit favored firms or business sectors. Some governments are also pumping the market with cheap credits from the clean development mechanism, which lowers prices and therefore makes it easier for industry to comply with restrictions.

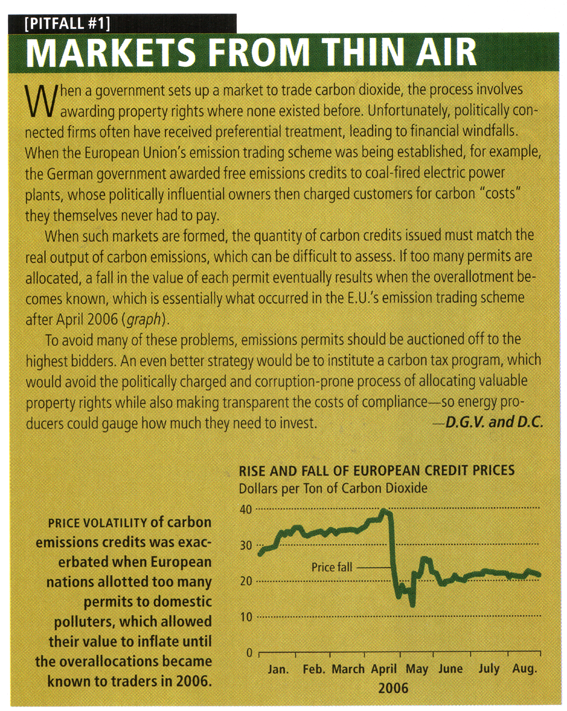

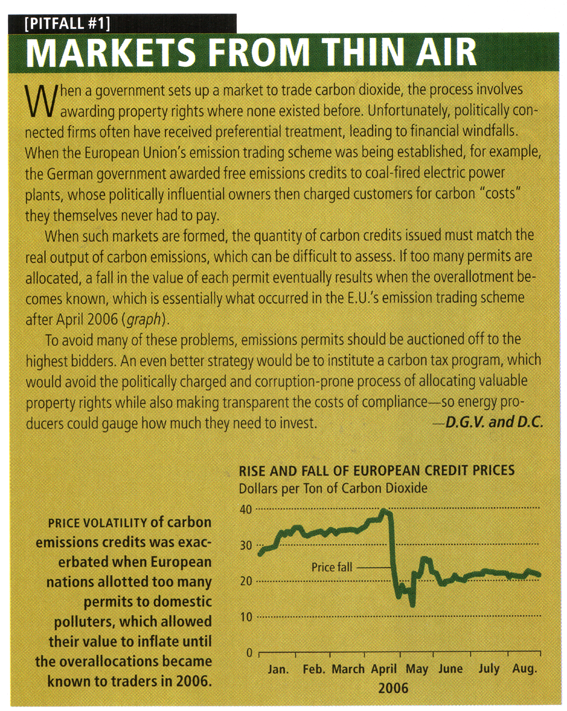

The E.U. has also encountered trouble in ensuring that traders get access to accurate information on the supply and demand of carbon credits. During the emissions trading scheme’s trial period, which began in 2005 and ends later this year, confusion in the market caused prices to gyrate from almost $40 per ton of CO2 to about a dollar today. The loss in value resulted when it became clear that governments massively oversupplied the market with permits, much as poorly managed central banks cause inflation by printing excess money. Brussels tightened the screws for the next trading period (2008 to 2012), which has sent the price for those permits to about $25 each.

Most controversial has been the distribution of permits to industry. The German government, for example, was keen to protect its coal industry. It awarded free credits to coal-fired electric power plants, whose owners then charged customers for carbon “costs” they never had to pay. Most of Europe’s electricity markets are not competitive, which has allowed utilities to find such ways to keep those extra revenues for themselves. Similar malfeasance has occurred in other countries, including the Netherlands, Spain and the U.K. In principle, the E.U. reviews each government’s allocation of credits so that favored companies are not subsidized unfairly. In practice, however, member states hold most of the political cards and are not hesitant to deal them as they deem fit.

Property From Thin Air

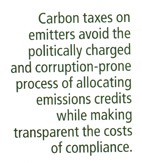

The establishment of a carbon market, like any market that involves awarding novel property rights, hinges on political choices. Some economists rightly think that a better approach would simply tax CO2 emitters, thereby avoiding the politically charged and corruption-prone process of allocating valuable property rights while also making transparent the costs of compliance. The tax approach, however, has been criticized by many environmentalists and most of the established industry. Environmentalists complain that tax systems (by design) make it difficult to predict the actual reduction in emissions. In practice, though, regulators can adjust tax levies as needed. More puzzling is opposition from industry. In theory, the chief benefit of taxation derives from the resulting certainty in the cost of emissions, a fact that makes it much easier to plan investments in power plants, and other large and long-lived infrastructure projects.

Although the logic of investment favors taxation, interested industries typically press for trading markets rather than taxes. They do so because they know that politicians tend to give away the emission credits for free to existing emitters, which constitutes huge windfalls that benefit the politically well-organized establishment. In the past, a few trading systems have auctioned some of their permits, but “big carbon”—including coal mining firms and owners of coal-fired power plants—is organizing to resist such attempts. In the E.U. system, the law forbids governments from auctioning more than one-tenth of carbon permits. U.S. lawmakers meanwhile are poised to embrace similar restrictions. At a summer 2006 hearing of the U.S. Senate to discuss the design of a potential emissions trading system, several American utilities urged that auctions, if used at all, should be limited to just five to 15 percent of total permits.

In other situations in which governments have handed out property rights to private entities—such as licenses for the new, so-called third-generation cell phones—administrators have not encountered such severe political opposition to auctions because industry is not already exploiting the public assets. But pollution markets, unlike other traded commodities such as corn and copper, are legal fiats; that is, they are designated as valuable property where none existed before. This situation is similar to that in the 19th century, when the U.S. Cavalry and overseers of the Homestead Act formally awarded large swaths of previously unclaimed property to settlers in the American West. When it comes to assigning property rights for assets that are already held, politically inspired handouts are the usual rule.

Some of these handouts are politically expedient because they help start a market in which entrenched interests—such as the coal lobby—would otherwise block progress. But if all the credits are given away, the entrenched interests become a bigger danger. The E.U. system envisions reallocating permits possibly every five years, which would deliver fresh handouts during each round, making it harder to dislodge the industries that produce most of the emissions.

It is not yet clear whether the E.U.’s trading system will cut emissions enough to enable Europe to comply with its commitments under the Kyoto Protocol. Many E.U. nations, especially those in the south, which tend to have the weakest regulatory institutions and political will to fulfill the Kyoto terms, are not on track to meet their targets. Nor is it apparent what will happen now that the E.U. has added 12 new, less-wealthy members (such as Bulgaria and Romania). Few of them have the capabilities to manage an emissions trading system. Some of these countries are now even challenging the emissions trading scheme in court because they claim its demands constitute a drag on economic growth. Our sense is that the most committed governments will work to ensure that the E.U. complies with its Kyoto commitments as a whole, notably by purchasing emission credits overseas from the clean development mechanism and from a similar system that allows governments to obtain credits in Russia and other “transition” countries. As is normal in international environmental law, it is likely that all countries that have joined the Kyoto Protocol will comply on paper even if formal observance does not actually do much to solve the underlying problem.

Growing Markets Worldwide

The E.U. experience teaches that trading systems, like all markets, do not arise spontaneously. Economic historians have determined that markets require strong underlying institutions to assign property rights, monitor behavior and enforce compliance. The E.U. has long kept track of other pollutants emitted by exactly the same industrial sources. Likewise, European administrative law courts have a long history of effective enforcement. Absent these institutions, emission credits in Europe would be worthless—just as bad money drives good from circulation, as economists often have observed. Yet even the E.U. is finding it difficult to create the strong regulatory institutions needed for an effective pollution control market. The European Monetary Union—the parent organization of the euro currency—faced similar challenges when leading countries such as France and Germany devalued the common currency by running huge budget deficits and amassing large debts. Even though the regulatory institutions were stronger than those fostering Europe’s carbon cap-and-trade system, the European Monetary Union proved relatively ineffective at keeping its powerful members in line when commitments grew inconvenient.

The central role of institutions and local interests accounts for why the real world has developed many different carbon trading systems. From these varied markets, a global trading system may eventually emerge. But the process of evolution will occur from the bottom up, rather than from the top down via an international treaty mandate such as the Kyoto Protocol. Because national circumstances vary so widely, this evolution will probably unfold over many decades. Integrating different national carbon markets would be akin to creating common currencies—a task that requires close cooperation and alignment of goals. It took the E.U. four decades to create the euro; it may take the world even longer to invent a single carbon credit that is legal tender and equally valuable around the globe.

For now, the European emissions trading system has emerged as the core of a nascent global market because it features the strongest institutions and exchanges the greatest volume of credits. During the next few years, however, the American public will likely grow more aware of the dangers greenhouse emissions pose to our climate and Congress will search for a political compromise to stem the threat. If the U.S. establishes a federal trading system in response, the scale of U.S. emissions trading could supplant the dominance of the E.U. in the budding global carbon market.

Exactly how the U.S. market unfolds will be complicated by two factors. One issue arises because several states in the northeast and the west, weary of the federal government’s inaction, are moving to create their own carbon trading systems. We doubt that these state systems will survive intact once a federal plan is in place, not least because electricity generation (which produces significant quantities of CO2) is fungible across most of the country and not easily amenable to a state-by-state approach. Nonetheless, some states may retain stricter rules, which could result in a patchwork of trading systems. The other complication relates to the fact that carbon emissions and investments are affected not only by explicit carbon regulations and prices, but also a wide array of other policy directives. Twenty-five states and the District of Columbia have, for example, already adopted standards for renewable power that are based, in part, on the goal of cutting CO2 releases. By 2020, these existing renewable portfolio standards will reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 108 million tons annually, say analysts at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Judged only by carbon reductions, renewable portfolio standards constitute a costly way to cut carbon because they concentrate investment on only a few power-generating technologies. Some experts wisely advocate a smarter “carbon portfolio standard” that would reward a wider range of low-carbon technologies such as advanced coal-fired power plants.

Wooing the Reluctant

Warts and all, emissions trading systems that are emerging from the bottom up are playing a key role in the drive to protect the climate. They send signals, through increased prices and the awarding of valuable carbon credits, that industrial economies must shake the carbon habit.

In the meantime, so-called emerging nations—such as China and India—pose the toughest obstacles to expanding emissions trading systems. These countries matter because their carbon dioxide effluent is rising at roughly three times the rate in the industrialized world. Total output from emerging nations will exceed that of the industrialized West within the next decade; China is already the world’s largest single emitter. Emerging nations also count because their economies often rely on obsolete technologies that offer the opportunity, at least in theory, to save money if newer emission controls were applied. The rub lies, of course, in the refusal of these nations to accept limits on their carbon emissions.

Trying to convince less-developed countries to join a full-blown, international emissions trading system would be unwise. Wary of economic constraints, yet unsure of their future emissions levels and the costs of stanching the flow, these states will likely demand generous headroom to grow. Although well-intentioned, agreeing to such a strategy would involve giving them lax emission caps, which would be like printing excess money. It would undercut efforts to control emissions elsewhere because surplus permits would flood markets. Administrators of the Kyoto Protocol struck exactly such a deal with Russia and Ukraine to convince them to join; both countries had refused unless they were given many free permits. As a consequence, the E.U. had to erect special barriers to prevent the excess paper credits from damaging real emissions reductions within the European market.

Rather than trying to monetize all emissions in emerging economies, the clean development mechanism offers a better compromise in theory because it promises to constrain trading to areas where developing countries have made actual cuts. And because the E.U. possesses the biggest market for emission credits, the clean development mechanism’s prices have converged on those set there.

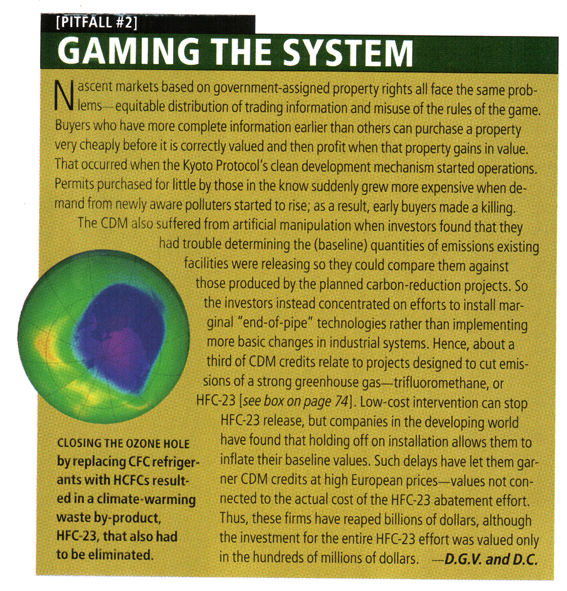

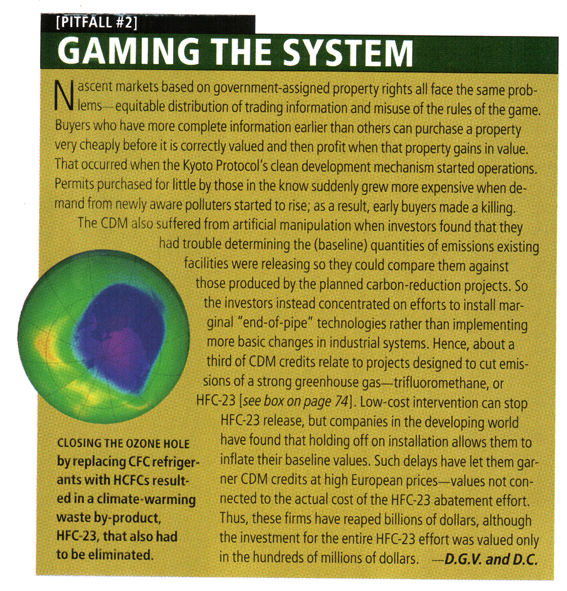

Gaming the System

In reality, however, the concept that underpins the clean development mechanism has a dark side. Investors find it difficult to identify the baseline emissions values for many projects—the “business-as-usual” scenario against which new project emissions are compared. So they instead have focused on projects to install marginal “end of pipe” technologies, rather than more fundamental changes in energy systems. About a third of the clean development mechanism credits stem from projects aimed at controlling just one industrial gas, trifluoromethane, or HFC-23, a byproduct of industrial processes that is 12,000 times as strong as carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas.

Everyone agrees that HFC-23 releases must be halted; the debate is how best to do so. All the plants in the industrialized world voluntarily have installed inexpensive devices to remove the chemical, and leading firms have shared the technology with all comers. But manufacturers in the developing world have discovered that holding off on installation allows them to inflate their baseline values. By so doing, they earn generous clean development mechanism credits with prices set at the high European levels—prices that are not connected to the actual cost of the upgrades for HFC-23. As a result, these industries are reaping up to $12.7 billion through 2012, according to our Stanford University colleague, attorney Michael Wara, when only $136 million is needed to pay for the HFC-23-removal technology.

A better approach for dealing with HFC-23 and other industrial gases would be to simply pay directly for the necessary equipment. This method was employed by the successful Montreal Protocol to preserve the ozone layer. The E.U. has further exacerbated the clean development mechanism debacle by honoring any credit that is approved under the mechanism’s rules, which are set through a cumbersome committee process under the Kyoto Protocol. Because HFC-23 projects produce huge numbers of easily verifiable credits, European governments have rushed to purchase them even though they know that the reductions they signify are dubious. Along the way, the practice has eclipsed more effective projects that are more complex to design and monitor. As the U.S. develops its own carbon market, it should set its own tighter rules to govern whether participants can gain credit from the clean development mechanism permits and other such “offset” programs.

A Better Way

An improved clean development mechanism alone will not be enough to encourage developing countries to engage, and pushing those countries to cap their emissions will backfire. A better approach would focus on areas where these countries existing interests align with the goal of cutting carbon. Driven by worries over energy security, for example, China has moved to boost energy efficiency, an effort that by 2020 could cut annual carbon emissions by about 300 million tons a year. Meanwhile, calculations by our research program suggest that India’s push for an expanded civilian nuclear power program could lower carbon emissions by as much as 150 million tons a year. For comparison, the entire E.U. effort to meet the Kyoto targets will reduce releases by only about 200 million tons annually and the 100 hundred largest clean development mechanism projects add up to just 100 million tons per annum. Eventually these countries must invest to lessen carbon output explicitly. Until then, however, much untapped potential exists to pursue other programs that align with their interests while also reducing carbon emissions.

Of course, not all policies automatically help the situation. China is investing in new technologies that produce oil substitutes from coal, an egregiously carbon-intensive way to manufacture liquid fuels. As more countries seek energy security, special efforts are needed to work on technologies that allow them to achieve those goals not at the expense of protecting Earth’s climate.

Even as political pressure for action grows, recent developments in energy markets have in some ways made it more difficult to tame carbon emissions. The rising price of oil has, for instance, encouraged higher energy efficiencies, which cuts carbon output. But higher petroleum prices have also lifted those of natural gas. As gas becomes dear, utilities across the world are opting to build coal-fired, rather than gas-fired, power plants. Until advanced coal-combustion technologies become widely available that allow CO2 to be captured and stored safely underground, the shift to coal is bad news for climate change because coal plants usually emit about twice the CO2 per kilowatt-hour of electricity that gas plants do.

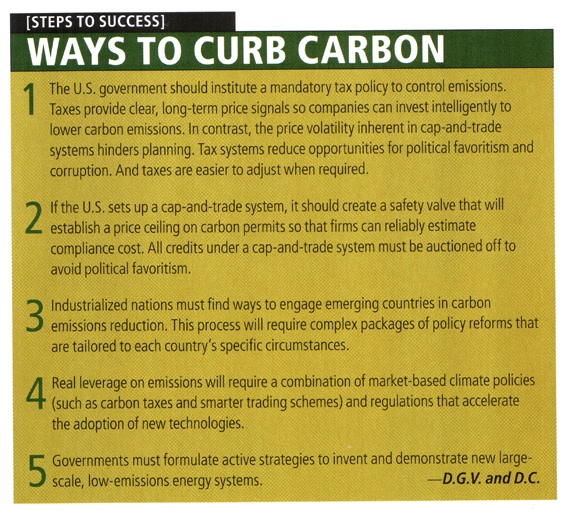

A Five-Step Plan

Given the scale of the climate challenge and the consequences of delay, four steps need to be taken to mobilize a more effective strategy.

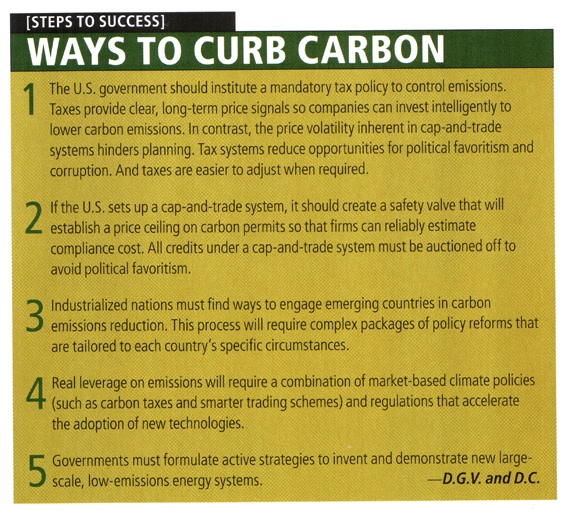

First, the U.S. should establish a mandatory tax policy to control the output of greenhouse gases. The politics are likely to favor a cap and trade system, but we favor taxes for several reasons. Taxes give clear, long-term price signals that make it easier for firms to make intelligent investments that will cut carbon emissions, whereas the price volatility of cap-and-trade systems impedes wise planning. Tax systems are also more transparent. Although hardly free from loopholes and other distortions, they offer fewer opportunities for political favoritism and corruption. And because taxes do not rest on property rights, they are easier to adjust when needed.

It is disappointing to see how quickly many U.S. policy makers have settled on the cap-and-trade approach without permitting a proper debate to occur on the use of taxes. If Congress prefers a cap-and-trade system, a smart compromise would be to create a “safety valve” that places a ceiling on prices so that industry has some certainty about the cost of compliance. This price, which essentially transforms the trading scheme into a tax, must be high enough so that it sends a credible signal that emitters must invest in technologies and practices that lower carbon emissions. And under any cap-and-trade system, it is crucial that all the credits be auctioned. Politically, it may be essential to hand out a small fraction of credits to pivotal interest groups. But our planet’s atmosphere is a public resource that must not be given away to users. Whenever this maxim has been ignored, pollution markets become politicized and companies focus their attention on gaming the permit allocation process.

Second, industrialized countries must develop a smarter strategy for engaging emerging markets. Clean development mechanism credit purchasers—notably the E.U. and Japan—need to lobby the mechanism’s executive board for comprehensive reform. Their lobbying will be more effective if they also restrict access to their home markets to credits from the clean development mechanism that have firmly established baselines and entail bona fide reductions. As the U.S. plans a climate policy, it should set its own tighter rules regarding such credits.

Seriously engaging developing countries will require complex packages of policy reforms that are tailored to each country’s situation. Most of the needed policies will occur within countries, but some cooperative international efforts will be essential as well, such as new schemes to share technology or fund transitions to less carbon-intensive fuels. The dozen or so largest emitters should convene a forum outside the Kyoto process to devise the needed strategies. Once started, success in this process would also enliven the broader Kyoto process.

Third, governments must accept that real leverage on emissions will require a combination of market-based climate policies (such as carbon taxes and smarter trading schemes) and a set of measures to support indirect, but effective and economical pressure to cut carbon and adopt new technologies. Encouraging more efficient use of energy requires, for example, not only higher energy prices but also equipment standards and mandates because many energy users (especially residential users) are insufficiently responsive to price signals alone.

Finally, governments must adopt active strategies to invent and apply new technologies. Formulating such plans must confront what we call the “price paradox.” If today’s European carbon prices were applied to the U.S., most utilities would not automatically install new power generation technologies, according to a study by the Electric Power Research Institute. In much of America, conventional coal-fired power plants would still be cheaper than nuclear power, wind farms or turbines fired with natural gas. Raising carbon prices to perhaps $40 per ton of CO2 or higher would encourage greater adoption of new technology, but that option seems politically unlikely. Ultimately, the belief that prices alone will solve the climate problem is rooted in the fiction that investors in large-scale and long-lived energy infrastructures sit on a fence waiting for higher carbon prices to tip their decisions. In fact, many factors stifle the implementation of novel low-carbon policies.

Energy R&D Investment

It is sobering to note that true solutions to the carbon problem will require massive deployment of new energy systems that emit little or no carbon and yet are reasonably competitive with current methods [see “A Plan to Keep Carbon in Check,” by Robert H. Socolow and Stephen W. Pacala; Scientific American; September 2006]. Getting those new technologies on line will require more than price signals because no company on its own will invest in the necessary speculative and costly research and development concepts. To address this predicament, the federal government will have to fund the required research and engineering projects at corporate, university and federal laboratories. Such public-led investments have historically delivered huge, but hard-to-quantify returns to society. Other useful schemes include research tax credits and special mechanisms to reduce risks from uncertain and changing regulations.

Unfortunately, current U.S. government investment in energy research lags. Federal support of energy R&D peaked in the early 1980s at around $8 billion a year (in 2002 dollars). Since then, it has declined sharply and reached a plateau around $3 billion to $4 billion a year—a tiny fraction of the roughly $100 billion of total public research and development funding in the U.S. Public support for energy research is now inching up, but the effort falls short of that needed to tackle the climate challenge. Private energy R&D support is also rising a bit—witness Silicon Valley’s investment in emerging “clean-tech” companies. Investors, however, tend to focus on technologies that are nearing commercial application and potential profit. In the past, the federal R&D tax credits have encouraged firms to spend more on new technology, but Congress has failed to renew the necessary legislation.

To effectively address the climate problem, progress will be needed on all four of the aforementioned fronts. Successors to the Kyoto Protocol will need to be more flexible to accommodate the diversity that will inevitably arise as each country formulates its own approach while at the same time creating strong incentives for countries to implement policies that actually yield substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Although we need to get the science and engineering right, the biggest danger in the area of global climate change lies in the difficult task of crafting human institutions that are up to the job.

More To Explore

Program on Energy and Sustainable Development - Climate Change Research Platform.

Architectures for Agreement: Addressing Global Climate Change in the Post-Kyoto World. Joseph E. Aldy and Robert N. Stavins (editors). Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Is the Global Carbon Market Working? Michael Wara. Nature, Vol 445, pages 595-596; 8 February 2007.

Design of a Cap and Trade System for California - Market Advisory Committee to the California Air Resources Board, May 23,2007.

Promoting Low-Carbon Electricity Production. - Jay Apt, David W. Keith and M. Granger Morgan, Issues in Science and Technology, Spring 2007.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels have risen over time but at rates that vary by region and circumstances. These patterns help explain why the United States left the Kyoto treaty, while the European Union and Japan remain committed to complying with their treaty obligations. The U.S. saw a period of rapid economic growth and increased consumption of fossil fuels over the last few decades, leading to a corresponding large increase in carbon dioxide emissions. For the E.U. and Japan, national emissions grew at a much slower rate, due in part to slower economic expansion, fortuitous changes in their energy systems and societal choices to use energy more efficiently. Even though their Kyoto targets are in sight, both the E.U. and Japan will need to purchase international carbon credits, notably from developing countries through the clean development mechanism, to augment their domestic efforts to reduce emissions.

Kyoto regulates all sources of carbon dioxide as well as other greenhouse gases, but reliable long-term data by country are available only for carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels (which accounts for about two-thirds of the human contribution to global warming). Emissions from the E.U. are shown for the 15 members that negotiated as a block when the Kyoto agreement was finalized in 1997, although since then another 12 countries have joined the E.U.—D.G.V. and D.C.

Data on emissions comes from the Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, and the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Kyoto targets and baselines are from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Carbon Markets, Prices and Volume

Initially, nascent carbon markets traded independently of one another and at different price levels. As clean development mechanism credits have been applied to the European Union’s emissions trading scheme, prices in these two markets are beginning to converge. Prices and trading volumes reflect many factors, including differences in the rigor of emission caps, enforcement standards, project monitoring and auditing. Like money, the paper itself is worthless: carbon credits are only as valuable as the credibility of the organizations that back them. [In this figure the area of the circles represent the volume of trading in the world’s five largest carbon markets, with prices on the vertical axis.]

More changes are already underway. The U.K.’s own emission trading system has ended and is now supplanted by the E.U.’s emissions trading scheme; at this writing a new national market has just started in Australia; one may soon appear in Canada, and two state-based trading systems are under development in the northeastern United States and in the west coast states.

A note on the data: the N.S.W. market does not release prices; instead, we infer a price ceiling from the penalty for non-compliance in the system, the maximum amount a market participant would pay to buy a carbon credit. The clean development mechanism does not release prices for all projects, so we only display a subset of those projects for which we were able to obtain price estimates from an industry group, PointCarbon. Clean development mechanism data points represent individual clean development mechanism projects; all other market data is monthly trading volumes and weighted prices.—D.G.V. and D.C.

Data on prices and volumes comes from the individual markets, the World Bank Carbon Finance Unit, and PointCarbon, a private sector carbon market analyst.

KEY:

Twenty-five states and the District of Columbia have independently enacted a Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), which require that a certain portion of the state’s energy consumption come from renewable energy. The magnitudes of RPS requirements, and the definition of what counts as “renewable,” varies from state to state, but in most these policies have encouraged substantial investment in new energy forms. Wind power, especially, has benefited from these policies; other electricity generation technologies, such as biomass, and solar thermal and solar photovoltaic systems, are poised to take advantage of RPS requirements as well.

In the absence of meaningful federal action, two groups of states have gone beyond RPS and enacted direct climate policies. Ten northeastern states have formed the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), a mandatory program that caps greenhouse gas emissions. Member states will allocate emissions credits, much like was done in the European Union’s carbon trading program, and trade between one another. Meanwhile, several western states led by California, have recently announced the Western Climate Initiative (WCI). This nascent program aims to establish a regional carbon trading market similar to RGGI. The WCI also includes two Canadian provinces, British Columbia and Manitoba. Both efforts are still forming the rules that will govern their operation, including rules on whether overseas “offsets,” such as the clean development mechanism, will be legal tender.—D.G.V. and D.C.

Data for state RPS policies comes from the North Carolina Solar Center’s Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency (DSIRE). The map in the figure was provided by GIS data from the United States Geological Survey’s National Atlas. Information on state climate policies comes from those groups’ websites, and Joshua Bushinsky of the Pew Center on Global Climate Change.

As Congress debates how to cut climate-warming emissions, insights drawn from the European carbon market can help. (Because of the timeliness of this issue, the editors of Scientific American decided to publish this article online in advance of its publication in the December issue.)

The odds are high that humans will warm Earth’s climate to worrisome levels during the coming century. Although fossil-fuel combustion has generated most of the buildup of climate-altering carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere, effective solutions will require more than just designing cleaner energy sources. Equally important will be establishing institutions and strategies—particularly markets, business regulations and government policies—that provide economies with incentives to apply innovative technologies and practices that reduce emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases.

The challenge is immense. Traditional fossil-fuel energy is so abundant and inexpensive that climate-friendly substitutes have little hope of acceptance without robust policy support. Meanwhile, for nearly two decades, negotiations on binding treaties that limit global emissions have struggled. But policy makers in Europe and other regions where public concern about climate change is strongest have already implemented significant initiatives to limit release of CO2. Lessons from these endeavors can help governments and world bodies fashion more effective strategies to protect the planet’s climate. Policy makers in the United States, which historically has produced more CO2 emissions than any other nation while doing relatively little to tame the flow, can in particular learn much about creating viable carbon-cutting markets by studying Europe’s recent experience. Based on these insights, we offer several concrete suggestions on how the U.S. should go about constructing an effective national climate policy.

A Global Approach

Until recently, nearly all policy debate about building institutions to protect Earth’s climate focused on the global level. Successful climate policy, thought analysts, activists and politicians, hinged on signing binding international treaties because the activities that cause climate change are worldwide in scope. Such an approach was needed because conventional wisdom assumed that if national governments merely acted alone, without global coordination, industries would simply relocate to where regulation was more lax.

This globalist theory underlay the negotiation of the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which called for all countries to work in good faith to address the climate problem and created a new organization to oversee its implementation. That treaty spawned negotiations to produce more demanding agreements, leading to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. Under Kyoto, the industrialized states—including the U.S., the European Union (E.U.), Japan and Russia—agreed in principle to individually tailored obligations that, if implemented, would have cut industrial emissions on average about five percent below 1990 levels. But developing countries, which placed a higher priority on economic growth, refused to accept caps on their emissions. They argued that responsibility for greenhouse gas pollution fell squarely on the industrialized world.

Clean Development Mechanism

Without any practical way to force developing nations to control their emissions, the Kyoto signers instead reached a compromise known as the clean development mechanism. Under this scheme, investors could earn credits for projects that cut emissions in developing nations even though the host country faced no binding restriction on its output of these gases. A British firm that faces strict (and thus costly) limits on its emissions at home, for example, might invest to build wind turbines in China. The company would then accrue credits for the difference between the “baseline” emissions that would have been released had the Chinese burned coal to generate electricity and the essentially zero emissions discharged by the wind farm. China would gain foreign investment and energy infrastructure, while the British firm could meet its environmental obligations at lower cost because credits earned overseas are often less expensive than reducing emissions at home.

The market for clean development mechanism credits has since exploded in size, accounting for about a third of a percent of world’s greenhouse emissions and around $4.4 billion in annual value.

Making Agreements Stick

Although the Kyoto proceedings rapidly yielded an accord on paper, the real-world impact on global warming is small. Industrialized nations, where the obligations are most demanding, have implemented restrictions in an uneven fashion. Key countries—notably the U.S., but also Australia and Canada—have ignored the Kyoto strictures because they found them too costly or politically inconvenient. The U.S. economy, for instance, grew rapidly in the late 1990s, which raised its emissions output, making meeting the Kyoto targets even harder.

History shows that broad international treaties usually fail to find solutions to difficult problems. That is because these pacts normally reflect the interests of their least enthusiastic members and are often codified through weak commitments with easy escape clauses for governments that will not readily honor their agreements. Pushing tougher constraints on unwilling governments rarely works because reluctant nations can just remain aloof, as most developing countries and the U.S. have in the Kyoto process. (By contrast, the successful efforts to protect earth’s ozone layer were created with U.S. leadership. They also hinged on a special financing scheme to pay recalcitrant developing countries for the cost of instituting deep cuts in emissions, an option that is an essential part of addressing the climate change problem, but one that is much harder to carry out because the price tag is dramatically larger.)

In a few areas of international cooperation, such as the promotion of freer trade in goods and services, this dismal rule has not held because governments have tailored agreements to deliver tangible benefits to all key participants and have continued to work cooperatively over many decades. These instances present some guidance for creating more effective efforts to slow climate change. The World Trade Organization (WTO), for instance, began as a modest set of practical commitments between countries that were interested in expanding trade. As experience and confidence grew in the system, these states invited others to join. Together, they built stronger structures for monitoring and enforcement as well as more sophisticated agreements, which in turn made it easier to insist that every member comply with all commitments—even those that proved problematic. The WTO’s record is by no means perfect, but the relative success of its process is encouraging. And after 50 years of sustained institution building, it today enforces binding obligations concerning complex and divisive economic issues among most countries. In fact, the “organization” in WTO’s name emerged only in the 1990s, four decades after governments negotiated their first trade agreement. Back in the 1940s those same states had tried to create a strong global trade organization, but their efforts failed for reasons quite similar to those of today’s Kyoto process—demanding potential agreements collapsed when powerful countries found them inconvenient, leaving fledgling the institution powerless to impose compliance.

Evaluating Climate Policy

The extended, step-by-step process by which governments established the WTO is only just starting in the field of climate change. Effective policy is emerging from the exertions of a core group of countries that are most committed to regulating emissions. While nearly all of those countries have joined the Kyoto treaty, each has formulated a different strategy to control release of greenhouse gases, which stands in sharp contrast to the integrated, global approach that most analysts have advocated. The variety of plans does not surprise many scholars of international politics, for it reflects the fact that governments harbor deep uncertainties in the best way to manage emissions, and that they also vary widely in their capabilities and styles. Equally unsurprising is that most climate policies were grafted onto existing regulatory institutions. Japan, for example, set policy targets by relying on its traditional process of coordinating of key ministries (notably, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry). Norway, meanwhile, has pursued a different path, levying a carbon tax on its large oil and natural gas industry, a relatively straightforward task given that the Norwegian government owns most of the nation’s petroleum business.

The efforts to limit greenhouse gases within the E.U. are key because the withdrawal of the U.S. left the E.U. as the largest political entity following a comprehensive plan for regulation. Naturally, the Union tailored its program to match its existing regulatory capabilities. For the 55 percent of its total emissions produced by the building, transportation and other dispersed sectors that are difficult to monitor, the E.U. and its member states have extended a wide array of existing policies. These rules include, for instance, voluntary (soon to be binding) automotive fuel economy targets that were negotiated with the car makers. By next year, new vehicles sold in Europe are to achieve, on average, at least 41 miles a gallon for gasoline-fueled autos and at least 44 miles a gallon for diesel cars. (Automobiles in the U.S., by contrast, currently need only to reach 27.5 miles a gallon by 2010, and even fewer miles per gallon for trucks and sport utility vehicles. Actual U.S. average mileage is even lower due to various loopholes in the standards.)

The remaining E.U. sources—defined as producers of “industrial emissions,” including power plants—are fewer and larger, and thus easier to control. For these business segments, E.U. regulators designed an emissions trading scheme—also known as a cap-and-trade system—modeled on a successful U.S. acid rain-reduction program of the 1990s. Under this arrangement, every E.U. government allocates emission credits—each representing a ton of carbon dioxide gas per year—to its industrial plants. The companies then decide individually whether it is cheaper to reduce emissions, which would free up extra permits for sale, or buy permits from others on the open market. If emission cuts prove costly, demand for permits will rise and so will their prices. Alternatively, prices fall if low-cost technologies for lessening carbon dioxide release appear, or slow economic growth weakens the industries that emit CO2. By limiting the total number of permits, E.U. regulators fix pollution levels while the market sets the price.

Start-up Difficulties

Several teething problems have emerged in the short history of the E.U. carbon market. Countries have struggled when handing out the property to be traded—the critical starting point for any market. Many of the allocation plans that each government devises have arrived late and have been incomplete. In some cases they were laden with politically inspired manipulations designed to benefit favored firms or business sectors. Some governments are also pumping the market with cheap credits from the clean development mechanism, which lowers prices and therefore makes it easier for industry to comply with restrictions.

The E.U. has also encountered trouble in ensuring that traders get access to accurate information on the supply and demand of carbon credits. During the emissions trading scheme’s trial period, which began in 2005 and ends later this year, confusion in the market caused prices to gyrate from almost $40 per ton of CO2 to about a dollar today. The loss in value resulted when it became clear that governments massively oversupplied the market with permits, much as poorly managed central banks cause inflation by printing excess money. Brussels tightened the screws for the next trading period (2008 to 2012), which has sent the price for those permits to about $25 each.

Most controversial has been the distribution of permits to industry. The German government, for example, was keen to protect its coal industry. It awarded free credits to coal-fired electric power plants, whose owners then charged customers for carbon “costs” they never had to pay. Most of Europe’s electricity markets are not competitive, which has allowed utilities to find such ways to keep those extra revenues for themselves. Similar malfeasance has occurred in other countries, including the Netherlands, Spain and the U.K. In principle, the E.U. reviews each government’s allocation of credits so that favored companies are not subsidized unfairly. In practice, however, member states hold most of the political cards and are not hesitant to deal them as they deem fit.

Property From Thin Air

The establishment of a carbon market, like any market that involves awarding novel property rights, hinges on political choices. Some economists rightly think that a better approach would simply tax CO2 emitters, thereby avoiding the politically charged and corruption-prone process of allocating valuable property rights while also making transparent the costs of compliance. The tax approach, however, has been criticized by many environmentalists and most of the established industry. Environmentalists complain that tax systems (by design) make it difficult to predict the actual reduction in emissions. In practice, though, regulators can adjust tax levies as needed. More puzzling is opposition from industry. In theory, the chief benefit of taxation derives from the resulting certainty in the cost of emissions, a fact that makes it much easier to plan investments in power plants, and other large and long-lived infrastructure projects.

Although the logic of investment favors taxation, interested industries typically press for trading markets rather than taxes. They do so because they know that politicians tend to give away the emission credits for free to existing emitters, which constitutes huge windfalls that benefit the politically well-organized establishment. In the past, a few trading systems have auctioned some of their permits, but “big carbon”—including coal mining firms and owners of coal-fired power plants—is organizing to resist such attempts. In the E.U. system, the law forbids governments from auctioning more than one-tenth of carbon permits. U.S. lawmakers meanwhile are poised to embrace similar restrictions. At a summer 2006 hearing of the U.S. Senate to discuss the design of a potential emissions trading system, several American utilities urged that auctions, if used at all, should be limited to just five to 15 percent of total permits.

In other situations in which governments have handed out property rights to private entities—such as licenses for the new, so-called third-generation cell phones—administrators have not encountered such severe political opposition to auctions because industry is not already exploiting the public assets. But pollution markets, unlike other traded commodities such as corn and copper, are legal fiats; that is, they are designated as valuable property where none existed before. This situation is similar to that in the 19th century, when the U.S. Cavalry and overseers of the Homestead Act formally awarded large swaths of previously unclaimed property to settlers in the American West. When it comes to assigning property rights for assets that are already held, politically inspired handouts are the usual rule.

Some of these handouts are politically expedient because they help start a market in which entrenched interests—such as the coal lobby—would otherwise block progress. But if all the credits are given away, the entrenched interests become a bigger danger. The E.U. system envisions reallocating permits possibly every five years, which would deliver fresh handouts during each round, making it harder to dislodge the industries that produce most of the emissions.

It is not yet clear whether the E.U.’s trading system will cut emissions enough to enable Europe to comply with its commitments under the Kyoto Protocol. Many E.U. nations, especially those in the south, which tend to have the weakest regulatory institutions and political will to fulfill the Kyoto terms, are not on track to meet their targets. Nor is it apparent what will happen now that the E.U. has added 12 new, less-wealthy members (such as Bulgaria and Romania). Few of them have the capabilities to manage an emissions trading system. Some of these countries are now even challenging the emissions trading scheme in court because they claim its demands constitute a drag on economic growth. Our sense is that the most committed governments will work to ensure that the E.U. complies with its Kyoto commitments as a whole, notably by purchasing emission credits overseas from the clean development mechanism and from a similar system that allows governments to obtain credits in Russia and other “transition” countries. As is normal in international environmental law, it is likely that all countries that have joined the Kyoto Protocol will comply on paper even if formal observance does not actually do much to solve the underlying problem.

Growing Markets Worldwide

The E.U. experience teaches that trading systems, like all markets, do not arise spontaneously. Economic historians have determined that markets require strong underlying institutions to assign property rights, monitor behavior and enforce compliance. The E.U. has long kept track of other pollutants emitted by exactly the same industrial sources. Likewise, European administrative law courts have a long history of effective enforcement. Absent these institutions, emission credits in Europe would be worthless—just as bad money drives good from circulation, as economists often have observed. Yet even the E.U. is finding it difficult to create the strong regulatory institutions needed for an effective pollution control market. The European Monetary Union—the parent organization of the euro currency—faced similar challenges when leading countries such as France and Germany devalued the common currency by running huge budget deficits and amassing large debts. Even though the regulatory institutions were stronger than those fostering Europe’s carbon cap-and-trade system, the European Monetary Union proved relatively ineffective at keeping its powerful members in line when commitments grew inconvenient.

The central role of institutions and local interests accounts for why the real world has developed many different carbon trading systems. From these varied markets, a global trading system may eventually emerge. But the process of evolution will occur from the bottom up, rather than from the top down via an international treaty mandate such as the Kyoto Protocol. Because national circumstances vary so widely, this evolution will probably unfold over many decades. Integrating different national carbon markets would be akin to creating common currencies—a task that requires close cooperation and alignment of goals. It took the E.U. four decades to create the euro; it may take the world even longer to invent a single carbon credit that is legal tender and equally valuable around the globe.

For now, the European emissions trading system has emerged as the core of a nascent global market because it features the strongest institutions and exchanges the greatest volume of credits. During the next few years, however, the American public will likely grow more aware of the dangers greenhouse emissions pose to our climate and Congress will search for a political compromise to stem the threat. If the U.S. establishes a federal trading system in response, the scale of U.S. emissions trading could supplant the dominance of the E.U. in the budding global carbon market.

Exactly how the U.S. market unfolds will be complicated by two factors. One issue arises because several states in the northeast and the west, weary of the federal government’s inaction, are moving to create their own carbon trading systems. We doubt that these state systems will survive intact once a federal plan is in place, not least because electricity generation (which produces significant quantities of CO2) is fungible across most of the country and not easily amenable to a state-by-state approach. Nonetheless, some states may retain stricter rules, which could result in a patchwork of trading systems. The other complication relates to the fact that carbon emissions and investments are affected not only by explicit carbon regulations and prices, but also a wide array of other policy directives. Twenty-five states and the District of Columbia have, for example, already adopted standards for renewable power that are based, in part, on the goal of cutting CO2 releases. By 2020, these existing renewable portfolio standards will reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 108 million tons annually, say analysts at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Judged only by carbon reductions, renewable portfolio standards constitute a costly way to cut carbon because they concentrate investment on only a few power-generating technologies. Some experts wisely advocate a smarter “carbon portfolio standard” that would reward a wider range of low-carbon technologies such as advanced coal-fired power plants.

Wooing the Reluctant

Warts and all, emissions trading systems that are emerging from the bottom up are playing a key role in the drive to protect the climate. They send signals, through increased prices and the awarding of valuable carbon credits, that industrial economies must shake the carbon habit.

In the meantime, so-called emerging nations—such as China and India—pose the toughest obstacles to expanding emissions trading systems. These countries matter because their carbon dioxide effluent is rising at roughly three times the rate in the industrialized world. Total output from emerging nations will exceed that of the industrialized West within the next decade; China is already the world’s largest single emitter. Emerging nations also count because their economies often rely on obsolete technologies that offer the opportunity, at least in theory, to save money if newer emission controls were applied. The rub lies, of course, in the refusal of these nations to accept limits on their carbon emissions.

Trying to convince less-developed countries to join a full-blown, international emissions trading system would be unwise. Wary of economic constraints, yet unsure of their future emissions levels and the costs of stanching the flow, these states will likely demand generous headroom to grow. Although well-intentioned, agreeing to such a strategy would involve giving them lax emission caps, which would be like printing excess money. It would undercut efforts to control emissions elsewhere because surplus permits would flood markets. Administrators of the Kyoto Protocol struck exactly such a deal with Russia and Ukraine to convince them to join; both countries had refused unless they were given many free permits. As a consequence, the E.U. had to erect special barriers to prevent the excess paper credits from damaging real emissions reductions within the European market.

Rather than trying to monetize all emissions in emerging economies, the clean development mechanism offers a better compromise in theory because it promises to constrain trading to areas where developing countries have made actual cuts. And because the E.U. possesses the biggest market for emission credits, the clean development mechanism’s prices have converged on those set there.

Gaming the System

In reality, however, the concept that underpins the clean development mechanism has a dark side. Investors find it difficult to identify the baseline emissions values for many projects—the “business-as-usual” scenario against which new project emissions are compared. So they instead have focused on projects to install marginal “end of pipe” technologies, rather than more fundamental changes in energy systems. About a third of the clean development mechanism credits stem from projects aimed at controlling just one industrial gas, trifluoromethane, or HFC-23, a byproduct of industrial processes that is 12,000 times as strong as carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas.

Everyone agrees that HFC-23 releases must be halted; the debate is how best to do so. All the plants in the industrialized world voluntarily have installed inexpensive devices to remove the chemical, and leading firms have shared the technology with all comers. But manufacturers in the developing world have discovered that holding off on installation allows them to inflate their baseline values. By so doing, they earn generous clean development mechanism credits with prices set at the high European levels—prices that are not connected to the actual cost of the upgrades for HFC-23. As a result, these industries are reaping up to $12.7 billion through 2012, according to our Stanford University colleague, attorney Michael Wara, when only $136 million is needed to pay for the HFC-23-removal technology.

A better approach for dealing with HFC-23 and other industrial gases would be to simply pay directly for the necessary equipment. This method was employed by the successful Montreal Protocol to preserve the ozone layer. The E.U. has further exacerbated the clean development mechanism debacle by honoring any credit that is approved under the mechanism’s rules, which are set through a cumbersome committee process under the Kyoto Protocol. Because HFC-23 projects produce huge numbers of easily verifiable credits, European governments have rushed to purchase them even though they know that the reductions they signify are dubious. Along the way, the practice has eclipsed more effective projects that are more complex to design and monitor. As the U.S. develops its own carbon market, it should set its own tighter rules to govern whether participants can gain credit from the clean development mechanism permits and other such “offset” programs.

A Better Way

An improved clean development mechanism alone will not be enough to encourage developing countries to engage, and pushing those countries to cap their emissions will backfire. A better approach would focus on areas where these countries existing interests align with the goal of cutting carbon. Driven by worries over energy security, for example, China has moved to boost energy efficiency, an effort that by 2020 could cut annual carbon emissions by about 300 million tons a year. Meanwhile, calculations by our research program suggest that India’s push for an expanded civilian nuclear power program could lower carbon emissions by as much as 150 million tons a year. For comparison, the entire E.U. effort to meet the Kyoto targets will reduce releases by only about 200 million tons annually and the 100 hundred largest clean development mechanism projects add up to just 100 million tons per annum. Eventually these countries must invest to lessen carbon output explicitly. Until then, however, much untapped potential exists to pursue other programs that align with their interests while also reducing carbon emissions.

Of course, not all policies automatically help the situation. China is investing in new technologies that produce oil substitutes from coal, an egregiously carbon-intensive way to manufacture liquid fuels. As more countries seek energy security, special efforts are needed to work on technologies that allow them to achieve those goals not at the expense of protecting Earth’s climate.

Even as political pressure for action grows, recent developments in energy markets have in some ways made it more difficult to tame carbon emissions. The rising price of oil has, for instance, encouraged higher energy efficiencies, which cuts carbon output. But higher petroleum prices have also lifted those of natural gas. As gas becomes dear, utilities across the world are opting to build coal-fired, rather than gas-fired, power plants. Until advanced coal-combustion technologies become widely available that allow CO2 to be captured and stored safely underground, the shift to coal is bad news for climate change because coal plants usually emit about twice the CO2 per kilowatt-hour of electricity that gas plants do.

A Five-Step Plan

Given the scale of the climate challenge and the consequences of delay, four steps need to be taken to mobilize a more effective strategy.

First, the U.S. should establish a mandatory tax policy to control the output of greenhouse gases. The politics are likely to favor a cap and trade system, but we favor taxes for several reasons. Taxes give clear, long-term price signals that make it easier for firms to make intelligent investments that will cut carbon emissions, whereas the price volatility of cap-and-trade systems impedes wise planning. Tax systems are also more transparent. Although hardly free from loopholes and other distortions, they offer fewer opportunities for political favoritism and corruption. And because taxes do not rest on property rights, they are easier to adjust when needed.

It is disappointing to see how quickly many U.S. policy makers have settled on the cap-and-trade approach without permitting a proper debate to occur on the use of taxes. If Congress prefers a cap-and-trade system, a smart compromise would be to create a “safety valve” that places a ceiling on prices so that industry has some certainty about the cost of compliance. This price, which essentially transforms the trading scheme into a tax, must be high enough so that it sends a credible signal that emitters must invest in technologies and practices that lower carbon emissions. And under any cap-and-trade system, it is crucial that all the credits be auctioned. Politically, it may be essential to hand out a small fraction of credits to pivotal interest groups. But our planet’s atmosphere is a public resource that must not be given away to users. Whenever this maxim has been ignored, pollution markets become politicized and companies focus their attention on gaming the permit allocation process.

Second, industrialized countries must develop a smarter strategy for engaging emerging markets. Clean development mechanism credit purchasers—notably the E.U. and Japan—need to lobby the mechanism’s executive board for comprehensive reform. Their lobbying will be more effective if they also restrict access to their home markets to credits from the clean development mechanism that have firmly established baselines and entail bona fide reductions. As the U.S. plans a climate policy, it should set its own tighter rules regarding such credits.

Seriously engaging developing countries will require complex packages of policy reforms that are tailored to each country’s situation. Most of the needed policies will occur within countries, but some cooperative international efforts will be essential as well, such as new schemes to share technology or fund transitions to less carbon-intensive fuels. The dozen or so largest emitters should convene a forum outside the Kyoto process to devise the needed strategies. Once started, success in this process would also enliven the broader Kyoto process.

Third, governments must accept that real leverage on emissions will require a combination of market-based climate policies (such as carbon taxes and smarter trading schemes) and a set of measures to support indirect, but effective and economical pressure to cut carbon and adopt new technologies. Encouraging more efficient use of energy requires, for example, not only higher energy prices but also equipment standards and mandates because many energy users (especially residential users) are insufficiently responsive to price signals alone.

Finally, governments must adopt active strategies to invent and apply new technologies. Formulating such plans must confront what we call the “price paradox.” If today’s European carbon prices were applied to the U.S., most utilities would not automatically install new power generation technologies, according to a study by the Electric Power Research Institute. In much of America, conventional coal-fired power plants would still be cheaper than nuclear power, wind farms or turbines fired with natural gas. Raising carbon prices to perhaps $40 per ton of CO2 or higher would encourage greater adoption of new technology, but that option seems politically unlikely. Ultimately, the belief that prices alone will solve the climate problem is rooted in the fiction that investors in large-scale and long-lived energy infrastructures sit on a fence waiting for higher carbon prices to tip their decisions. In fact, many factors stifle the implementation of novel low-carbon policies.

Energy R&D Investment

It is sobering to note that true solutions to the carbon problem will require massive deployment of new energy systems that emit little or no carbon and yet are reasonably competitive with current methods [see “A Plan to Keep Carbon in Check,” by Robert H. Socolow and Stephen W. Pacala; Scientific American; September 2006]. Getting those new technologies on line will require more than price signals because no company on its own will invest in the necessary speculative and costly research and development concepts. To address this predicament, the federal government will have to fund the required research and engineering projects at corporate, university and federal laboratories. Such public-led investments have historically delivered huge, but hard-to-quantify returns to society. Other useful schemes include research tax credits and special mechanisms to reduce risks from uncertain and changing regulations.

Unfortunately, current U.S. government investment in energy research lags. Federal support of energy R&D peaked in the early 1980s at around $8 billion a year (in 2002 dollars). Since then, it has declined sharply and reached a plateau around $3 billion to $4 billion a year—a tiny fraction of the roughly $100 billion of total public research and development funding in the U.S. Public support for energy research is now inching up, but the effort falls short of that needed to tackle the climate challenge. Private energy R&D support is also rising a bit—witness Silicon Valley’s investment in emerging “clean-tech” companies. Investors, however, tend to focus on technologies that are nearing commercial application and potential profit. In the past, the federal R&D tax credits have encouraged firms to spend more on new technology, but Congress has failed to renew the necessary legislation.

To effectively address the climate problem, progress will be needed on all four of the aforementioned fronts. Successors to the Kyoto Protocol will need to be more flexible to accommodate the diversity that will inevitably arise as each country formulates its own approach while at the same time creating strong incentives for countries to implement policies that actually yield substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Although we need to get the science and engineering right, the biggest danger in the area of global climate change lies in the difficult task of crafting human institutions that are up to the job.

More To Explore

Program on Energy and Sustainable Development - Climate Change Research Platform.

Architectures for Agreement: Addressing Global Climate Change in the Post-Kyoto World. Joseph E. Aldy and Robert N. Stavins (editors). Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Is the Global Carbon Market Working? Michael Wara. Nature, Vol 445, pages 595-596; 8 February 2007.

Design of a Cap and Trade System for California - Market Advisory Committee to the California Air Resources Board, May 23,2007.

Promoting Low-Carbon Electricity Production. - Jay Apt, David W. Keith and M. Granger Morgan, Issues in Science and Technology, Spring 2007.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels have risen over time but at rates that vary by region and circumstances. These patterns help explain why the United States left the Kyoto treaty, while the European Union and Japan remain committed to complying with their treaty obligations. The U.S. saw a period of rapid economic growth and increased consumption of fossil fuels over the last few decades, leading to a corresponding large increase in carbon dioxide emissions. For the E.U. and Japan, national emissions grew at a much slower rate, due in part to slower economic expansion, fortuitous changes in their energy systems and societal choices to use energy more efficiently. Even though their Kyoto targets are in sight, both the E.U. and Japan will need to purchase international carbon credits, notably from developing countries through the clean development mechanism, to augment their domestic efforts to reduce emissions.