Is the Oil Industry Off a Cliff or Just in a Down Cycle?

Low prices are forcing companies to curtail exploration and borrow to sustain dividends and stock value as the world looks to curtail emissions.

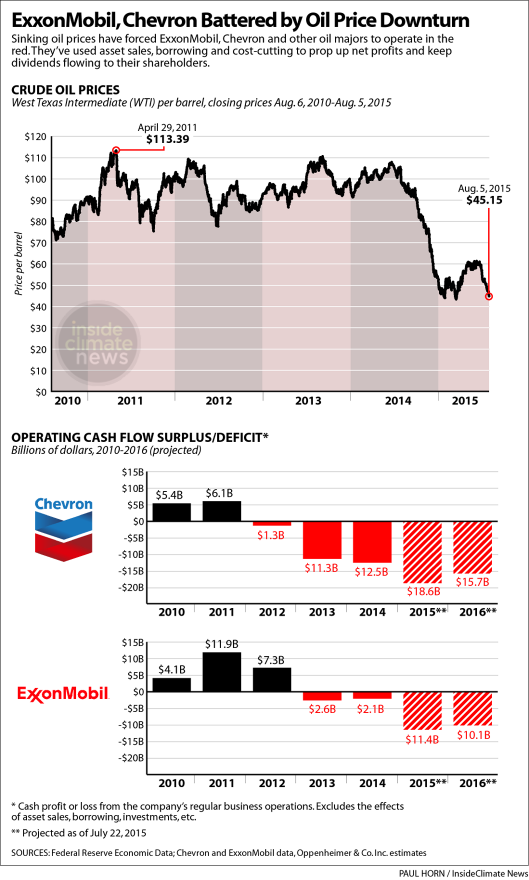

With the oil industry facing what could be its worst downturn in more than 45 years, the major companies are taking extraordinary, perhaps even desperate, measures to preserve their dividends. This is raising the question of whether the current price slump is just another in a long history of down business cycles, from which oil companies always emerge victoriously, or a sign of more deeply troubled times ahead.

The companies and Wall Street analysts argue that the downturn will reverse as all others have in the past because the world still needs oil, and a lot of it. But some worry that climate change regulations and other new threats could instead force the oil and natural gas business into a tailspin like the one the U.S. coal industry is experiencing.

What side of that argument you fall on will color how you see the oil companies’ current behavior. Oversupply has dropped crude prices to less than half of last year’s highs, and companies are propping up profits by cutting jobs, selling assets and slashing oil exploration.

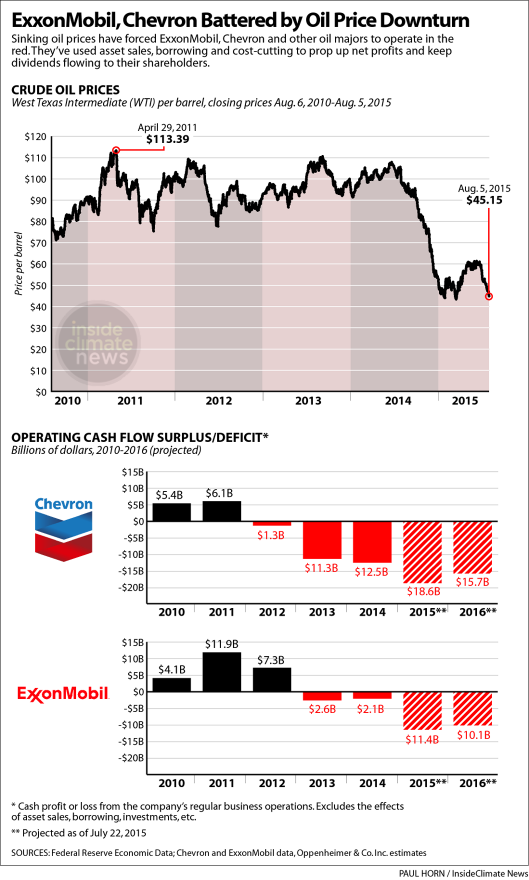

They are doing this to avoid reducing dividends—the main reason oil stocks remain an attractive investment. Many investors stick with them because of nearly automatic payouts of 3.7 percent to 6.5 percent— well above the 2.2 percent yield of the benchmark 10-year Treasury note. It’s so crucial to supporting share prices that ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, Royal Dutch Shell and others “are basically deficit spending” to sustain dividends, according to Fadel Gheit, managing director and senior oil analyst at Oppenheimer & Co.

In addition to market challenges, however, oil companies face something they’ve never dealt with before: A global call to shift the world’s economies to renewable and low-carbon energy. From the Bank of England to the Pope, international government groups and the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, there’s a growing push to phase out fossil fuels to save the world from catastrophic warming. This may leave the oil companies with billions of dollars in petroleum reserves that may never be tapped, making them “stranded assets,” some industry analysts say.

“They are leveraging themselves with the hope that the future will look a lot like the past, that oil prices will go back up and things will just go back to the way they were,” said Andrew Logan, director of the oil program at Ceres, a Boston nonprofit that manages a coalition of institutional shareholders with investments in oil companies. “With the issues around climate change and the way technological innovation is going, that seems to me like a very risky bet.

“If the price of oil is in a long-term low, you’re really setting yourself up to be in a bit of a death spiral.”

The oil industry’s troubles stem from a sudden collapse in oil prices last summer. U.S. crude that traded between $90 and $110 a barrel for most of four years crashed to less than $50 because U.S. production soared and total world output swamped global demand. After rallying recently, the global oil price fell back again, closing Wednesday at $45.15.

Many analysts now expect oil prices to stay low at least into next year. In a May report, Goldman Sachs had a worse prediction: That global oil prices would average between $60 and $65 per barrel for several years, and drop to $55 by 2020.

So far, the industry’s long-term commitment to dividend payouts has helped keep investors from fleeing even though growth prospects are grim and many oil company stocks have underperformed the market for several years. Many of the most widely held oil equities are down sharply this year, including ExxonMobil (-16.5 percent), Chevron (-25 percent), Shell (-13.8 percent) and ConocoPhillips (-28.9 percent).

After ExxonMobil and Chevron reported second-quarter earnings Friday that were down by half and by 90 percent, respectively, both companies’ stocks fell nearly 5 percent. That day, Exxon’s market value dropped by $19 billion and Chevron’s fell by $8.6 billion. Chevron shares closed at $84.03 Wednesday, well off its 52-week high of $129.53. Similarly, Exxon—which hit a high of $100.31 in the past year—closed Wednesday at $77.17.

Since prices crashed, oil companies have deferred more than 45 major projects, delaying $200 billion in spending, according to a report from consultant Wood Mackenzie. Projects that are expensive and technologically challenging were hurt the most, including many in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico, Africa and Canada’s oil sands.

Another potential threat comes in December, when world leaders will meet in Paris to negotiate a global climate pact aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions enough to prevent the worst effects of climate change. Similar efforts at a global accord have failed in the past. But even a limited agreement to restrain the burning of fossil fuels could undermine confidence in the oil industry’s projections for sustained demand growth.

“If we do get a global deal on climate that locks in a target for reducing emissions … then I think the fossil fuel companies do face a very bleak outlook,” said Mark Lewis, chief energy economist at Kepler Cheuvreux, a Paris-based brokerage.

At the same time, renewable energy technology is improving and becoming cheaper; regional and municipal governments are adopting limits on carbon dioxide emissions; and carmakers around the world are working to make electric cars and batteries more efficient and affordable.

Those developments and others have led researchers to predict that oil, gas and coal companies could be forced to leave a large share of their fossil fuel reserves in the ground. So far, investors don’t seem to be taking that risk into account, some industry analysts say.

During calls with investors over the past two weeks, executives of the world’s largest publicly traded oil companies said they are bracing for a prolonged period of weak prices and sharply lower earnings. But there was no reason to panic or revise long-term demand projections, the executives said. Most Wall Street analysts agree.

“This is just defensive mode, nothing more,” said Oswald Clint, an oil analyst at Bernstein Research. The oil companies have been around for more than a century, he said. “They have been through many cycles and know how to react.”

Severin Borenstein argues that the long-term outlook for oil companies remains strong.

“The world demand for oil is increasing again, and as the developing world continues to grow, demand’s going to continue to grow,” said Borenstein, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. “We’ve seen this transformation, and one of the first things people want is motorized transportation, and that’s a huge increase for the demand for oil.”

On the other hand, he said, “It’s very hard for an oil company to say, ‘Look, we’re an oil company. We don’t have a Plan B. If you want a Plan B, go buy some other stock, because if the demand for oil goes away, we go away,’ and I think that’s the reality of it.”

That’s a reality that U.S. coal companies are starting to contemplate. While demand for coal is still growing, the long-term outlook is much less rosy. Coal company stocks and profits have been pummeled by the combination of cheaper natural gas, China’s slowdown in demand, pollution regulations and an increasingly vocal backlash over the role fossil fuels have played in warming the planet.

Dozens of companies have filed for bankruptcy protection, and others are on shaky financial ground. Peabody Energy, one of the most vocal critics of the U.S. crackdown on harmful coal plant emissions, has been struggling to stay afloat. The company’s stock closed Wednesday at $1.10 per share, down 85.8 percent so far this year.

For oil companies, cutting the dividend would be a last resort.

“There is no reason to own a major oil company except for one thing—you are assured of dividends, and sometimes the dividend grows,” said Gheit, the Oppenheimer analyst. “It’s the closest thing to a CD, but with higher yield.”

If Chevron or Exxon had announced a dividend cut last Friday, their stocks would have fallen 10 percent instead of 5 percent, Gheit said. Chesapeake Energy, a struggling U.S. oil and gas company, saw its shares drop 11 percent in the days after it said it would stop paying its $0.0875 per share quarterly dividends beginning in the third quarter. The stock has lost more than half its value this year.

Now that oil prices are expected to remain low, some analysts are wondering if some of the world’s largest public oil companies will be forced to rein in their dividend. So far, all of the oil majors have halted or reduced their share buyback programs—which benefit shareholders by making each remaining share more valuable—but only Italy’s Eni has dared to cut its dividend.

If there is a prolonged period of sub-$60 crude oil, “even the majors could be forced to freeze or cut their dividend, which could sink their shares,” Gheit wrote in a report last month.

Oil stocks are “25-year investments; they’re always in demand; and it’s not like the economy at the moment can do without what they produce,” said Julian Poulter, executive director of the Asset Owners Disclosure Project, a London-based nonprofit pushing pension funds to take account of climate risks. “But the pension fund leaders are starting to realize, well, this is going to end at some point.”

Oil companies will have to resume investing in new projects to keep production from falling, according to Lewis, the energy economist at Kepler Cheuvreux. “Then people will be saying, thanks for cutting back your capex, and thanks for maintaining the dividend, but now your production is declining so your cash flow is going to be declining, so you’re still going to have a problem with paying your dividend.”

With the oil industry facing what could be its worst downturn in more than 45 years, the major companies are taking extraordinary, perhaps even desperate, measures to preserve their dividends. This is raising the question of whether the current price slump is just another in a long history of down business cycles, from which oil companies always emerge victoriously, or a sign of more deeply troubled times ahead.

The companies and Wall Street analysts argue that the downturn will reverse as all others have in the past because the world still needs oil, and a lot of it. But some worry that climate change regulations and other new threats could instead force the oil and natural gas business into a tailspin like the one the U.S. coal industry is experiencing.

What side of that argument you fall on will color how you see the oil companies’ current behavior. Oversupply has dropped crude prices to less than half of last year’s highs, and companies are propping up profits by cutting jobs, selling assets and slashing oil exploration.

They are doing this to avoid reducing dividends—the main reason oil stocks remain an attractive investment. Many investors stick with them because of nearly automatic payouts of 3.7 percent to 6.5 percent— well above the 2.2 percent yield of the benchmark 10-year Treasury note. It’s so crucial to supporting share prices that ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, Royal Dutch Shell and others “are basically deficit spending” to sustain dividends, according to Fadel Gheit, managing director and senior oil analyst at Oppenheimer & Co.

In addition to market challenges, however, oil companies face something they’ve never dealt with before: A global call to shift the world’s economies to renewable and low-carbon energy. From the Bank of England to the Pope, international government groups and the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, there’s a growing push to phase out fossil fuels to save the world from catastrophic warming. This may leave the oil companies with billions of dollars in petroleum reserves that may never be tapped, making them “stranded assets,” some industry analysts say.

“They are leveraging themselves with the hope that the future will look a lot like the past, that oil prices will go back up and things will just go back to the way they were,” said Andrew Logan, director of the oil program at Ceres, a Boston nonprofit that manages a coalition of institutional shareholders with investments in oil companies. “With the issues around climate change and the way technological innovation is going, that seems to me like a very risky bet.

“If the price of oil is in a long-term low, you’re really setting yourself up to be in a bit of a death spiral.”

The oil industry’s troubles stem from a sudden collapse in oil prices last summer. U.S. crude that traded between $90 and $110 a barrel for most of four years crashed to less than $50 because U.S. production soared and total world output swamped global demand. After rallying recently, the global oil price fell back again, closing Wednesday at $45.15.

Many analysts now expect oil prices to stay low at least into next year. In a May report, Goldman Sachs had a worse prediction: That global oil prices would average between $60 and $65 per barrel for several years, and drop to $55 by 2020.

So far, the industry’s long-term commitment to dividend payouts has helped keep investors from fleeing even though growth prospects are grim and many oil company stocks have underperformed the market for several years. Many of the most widely held oil equities are down sharply this year, including ExxonMobil (-16.5 percent), Chevron (-25 percent), Shell (-13.8 percent) and ConocoPhillips (-28.9 percent).

After ExxonMobil and Chevron reported second-quarter earnings Friday that were down by half and by 90 percent, respectively, both companies’ stocks fell nearly 5 percent. That day, Exxon’s market value dropped by $19 billion and Chevron’s fell by $8.6 billion. Chevron shares closed at $84.03 Wednesday, well off its 52-week high of $129.53. Similarly, Exxon—which hit a high of $100.31 in the past year—closed Wednesday at $77.17.

Since prices crashed, oil companies have deferred more than 45 major projects, delaying $200 billion in spending, according to a report from consultant Wood Mackenzie. Projects that are expensive and technologically challenging were hurt the most, including many in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico, Africa and Canada’s oil sands.

Another potential threat comes in December, when world leaders will meet in Paris to negotiate a global climate pact aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions enough to prevent the worst effects of climate change. Similar efforts at a global accord have failed in the past. But even a limited agreement to restrain the burning of fossil fuels could undermine confidence in the oil industry’s projections for sustained demand growth.

“If we do get a global deal on climate that locks in a target for reducing emissions … then I think the fossil fuel companies do face a very bleak outlook,” said Mark Lewis, chief energy economist at Kepler Cheuvreux, a Paris-based brokerage.

At the same time, renewable energy technology is improving and becoming cheaper; regional and municipal governments are adopting limits on carbon dioxide emissions; and carmakers around the world are working to make electric cars and batteries more efficient and affordable.

Those developments and others have led researchers to predict that oil, gas and coal companies could be forced to leave a large share of their fossil fuel reserves in the ground. So far, investors don’t seem to be taking that risk into account, some industry analysts say.

During calls with investors over the past two weeks, executives of the world’s largest publicly traded oil companies said they are bracing for a prolonged period of weak prices and sharply lower earnings. But there was no reason to panic or revise long-term demand projections, the executives said. Most Wall Street analysts agree.

“This is just defensive mode, nothing more,” said Oswald Clint, an oil analyst at Bernstein Research. The oil companies have been around for more than a century, he said. “They have been through many cycles and know how to react.”

Severin Borenstein argues that the long-term outlook for oil companies remains strong.

“The world demand for oil is increasing again, and as the developing world continues to grow, demand’s going to continue to grow,” said Borenstein, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. “We’ve seen this transformation, and one of the first things people want is motorized transportation, and that’s a huge increase for the demand for oil.”

On the other hand, he said, “It’s very hard for an oil company to say, ‘Look, we’re an oil company. We don’t have a Plan B. If you want a Plan B, go buy some other stock, because if the demand for oil goes away, we go away,’ and I think that’s the reality of it.”

That’s a reality that U.S. coal companies are starting to contemplate. While demand for coal is still growing, the long-term outlook is much less rosy. Coal company stocks and profits have been pummeled by the combination of cheaper natural gas, China’s slowdown in demand, pollution regulations and an increasingly vocal backlash over the role fossil fuels have played in warming the planet.

Dozens of companies have filed for bankruptcy protection, and others are on shaky financial ground. Peabody Energy, one of the most vocal critics of the U.S. crackdown on harmful coal plant emissions, has been struggling to stay afloat. The company’s stock closed Wednesday at $1.10 per share, down 85.8 percent so far this year.

For oil companies, cutting the dividend would be a last resort.

“There is no reason to own a major oil company except for one thing—you are assured of dividends, and sometimes the dividend grows,” said Gheit, the Oppenheimer analyst. “It’s the closest thing to a CD, but with higher yield.”

If Chevron or Exxon had announced a dividend cut last Friday, their stocks would have fallen 10 percent instead of 5 percent, Gheit said. Chesapeake Energy, a struggling U.S. oil and gas company, saw its shares drop 11 percent in the days after it said it would stop paying its $0.0875 per share quarterly dividends beginning in the third quarter. The stock has lost more than half its value this year.

Now that oil prices are expected to remain low, some analysts are wondering if some of the world’s largest public oil companies will be forced to rein in their dividend. So far, all of the oil majors have halted or reduced their share buyback programs—which benefit shareholders by making each remaining share more valuable—but only Italy’s Eni has dared to cut its dividend.

If there is a prolonged period of sub-$60 crude oil, “even the majors could be forced to freeze or cut their dividend, which could sink their shares,” Gheit wrote in a report last month.

Oil stocks are “25-year investments; they’re always in demand; and it’s not like the economy at the moment can do without what they produce,” said Julian Poulter, executive director of the Asset Owners Disclosure Project, a London-based nonprofit pushing pension funds to take account of climate risks. “But the pension fund leaders are starting to realize, well, this is going to end at some point.”

Oil companies will have to resume investing in new projects to keep production from falling, according to Lewis, the energy economist at Kepler Cheuvreux. “Then people will be saying, thanks for cutting back your capex, and thanks for maintaining the dividend, but now your production is declining so your cash flow is going to be declining, so you’re still going to have a problem with paying your dividend.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.