Is coal making a comeback?

Last September, Citigroup quietly released a report declaring that cheap natural gas was engaged in a “symbiotic relationship” with intermittent renewable forms of energy – i.e. solar and wind – and that together the two would displace enough coal to take a big bite out of carbon emissions. Over the past month, the report has resurfaced and caught the interest of both greens and natural gas pushers as a sort of road map for the way forward.

The report is noticeable because it is, at first glance, counterintuitive: Just as cheap natural gas, by virtue of its cheapness, is displacing coal, one would expect it to also displace all other means of generating electricity, including renewables. Yet the report reminds us that because solar and wind are intermittent – their power output bobbles up and down over the course of a day thanks to clouds and wind fluctuations and sunset – they need some other sort of quick-ramping power to back them up. And, aside from hydropower, the best option is a natural gas turbine, much like a jet engine, that can be fired up and putting power into the grid in mere minutes. Thus, the more renewables that are added to the grid, the more natural gas will be needed to back them up.

The backup – or reserve – has a cost, just like anything. And since it’s necessitated by the intermittency of solar and wind, the utility will typically add that cost to the price they’re paying for the solar or wind. So, the lower the cost of natural gas, the lower these so-called ancillary costs. The lower the ancillary costs, the cheaper the solar and wind, making them more desirable. Hand in hand, cheap and plentiful natural gas and renewables will topple dirty coal.

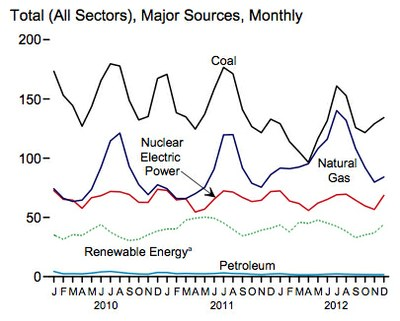

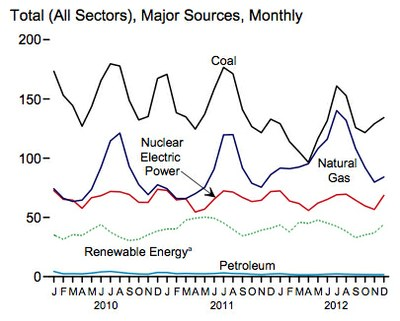

That was six months ago. This is now. Last week, another report was released that takes a bit of the sheen off this scenario. This one was from the Energy Information Administration, and it shows an interesting trend, nicely illustrated by this graph:

It’s easy to see why those who would like to see coal go away were celebrating last spring, when the blue natural gas line and the black coal line shared a kiss, marking the first time that the two took up an equal share of the electricity mix. For that brief moment it truly appeared as if natural gas would overtake coal once and for all, leading to a reduction in overall emissions (natural gas burns about twice as cleanly as coal, methane leaks during the extraction and transportation process notwithstanding), and clearing the way for renewables to gain a stronger foothold in the mix.

That didn’t happen, or hasn’t happened. As the graph shows, as soon as the winter electricity consumption surge hit, coal began to regain its dominance, so that by the end of 2012, coal was providing 40 percent of our electricity, natural gas 25 percent and wind and solar, combined, a mere 4 percent. So much for all that symbiosis.

As the data made the rounds this week, alarm bells understandably went off around the green blogosphere. It became clear that relying on the market, alone, to fight their war on coal wasn’t going to be effective.

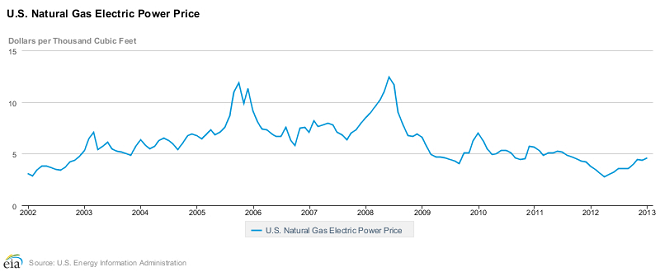

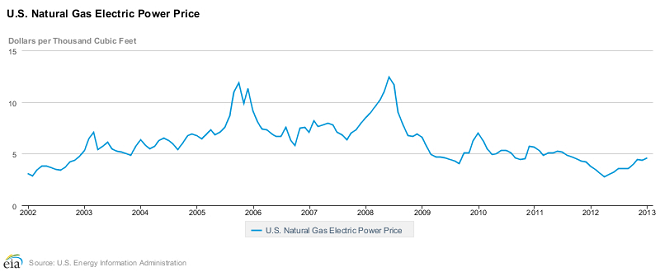

We shouldn’t be so surprised. Critics of the switch to natural gas have long warned that the fuel is too volatile, price-wise, to be relied upon as a major source of baseload electricity generation. That’s true even now, when we’re in the midst of a natural gas glut so big, with prices generally so low, that natural gas drillers in many areas have simply given up. The cost of a thousand cubic feet of natural gas swung from $2.80 last spring to about $4.50 this January, thanks in part to additional demand from the power sector, but also to new demand from manufacturers and millions of homes that use the fuel to heat their homes. As the prices went up, utilities simply switched back to that old, boring, but stable coal.

But coal-bashers shouldn’t give up hope. In the short-term, natural gas prices should drop as temperatures rise this spring. Utilities will fire up that extra natural gas generating capacity that they’ve constructed over the past decade or so, and perhaps the cleaner-burning fuel will surpass coal in the electricity generating mix – at least for a month or two. In the long term, as more and more coal plants are retired, the utilities will lose the ability to quickly switch back to coal even when natural gas prices swing back upward, as they surely will, especially if the fuel’s use in transportation grows, or if the feds decide this summer to allow large-scale export of liquefied natural gas. Just this week, NV Energy became the most recent Western utility to announce it’s abandoning coal in favor of natural gas and renewables.

Meanwhile, the experience should provide a lesson to those who now are building the energy infrastructure that will be with us for the next several decades: If you’ve got a choice between building natural gas or renewable infrastructure, go with the latter. The intermittency hurdle with solar and wind is a substantial one, yes, but it’s surpassable, too. Large scale energy storage technology would pretty much erase the hurdle (if we can ever figure it out), and so-called “geographic smoothing,” where you combine renewable resources over a vast geographical area so that a wind farm in, say, Wyoming can back up a solar plant in California, would ease the need for huge natural gas peaking plants. Yes, that would require new transmission lines and a different way of doing business, but the same is true for a big buildup of natural gas.

Yes, there can be a symbiotic relationship between natural gas and renewables. The question is: Are we prepared to live with its offspring?

The report is noticeable because it is, at first glance, counterintuitive: Just as cheap natural gas, by virtue of its cheapness, is displacing coal, one would expect it to also displace all other means of generating electricity, including renewables. Yet the report reminds us that because solar and wind are intermittent – their power output bobbles up and down over the course of a day thanks to clouds and wind fluctuations and sunset – they need some other sort of quick-ramping power to back them up. And, aside from hydropower, the best option is a natural gas turbine, much like a jet engine, that can be fired up and putting power into the grid in mere minutes. Thus, the more renewables that are added to the grid, the more natural gas will be needed to back them up.

The backup – or reserve – has a cost, just like anything. And since it’s necessitated by the intermittency of solar and wind, the utility will typically add that cost to the price they’re paying for the solar or wind. So, the lower the cost of natural gas, the lower these so-called ancillary costs. The lower the ancillary costs, the cheaper the solar and wind, making them more desirable. Hand in hand, cheap and plentiful natural gas and renewables will topple dirty coal.

That was six months ago. This is now. Last week, another report was released that takes a bit of the sheen off this scenario. This one was from the Energy Information Administration, and it shows an interesting trend, nicely illustrated by this graph:

It’s easy to see why those who would like to see coal go away were celebrating last spring, when the blue natural gas line and the black coal line shared a kiss, marking the first time that the two took up an equal share of the electricity mix. For that brief moment it truly appeared as if natural gas would overtake coal once and for all, leading to a reduction in overall emissions (natural gas burns about twice as cleanly as coal, methane leaks during the extraction and transportation process notwithstanding), and clearing the way for renewables to gain a stronger foothold in the mix.

That didn’t happen, or hasn’t happened. As the graph shows, as soon as the winter electricity consumption surge hit, coal began to regain its dominance, so that by the end of 2012, coal was providing 40 percent of our electricity, natural gas 25 percent and wind and solar, combined, a mere 4 percent. So much for all that symbiosis.

As the data made the rounds this week, alarm bells understandably went off around the green blogosphere. It became clear that relying on the market, alone, to fight their war on coal wasn’t going to be effective.

We shouldn’t be so surprised. Critics of the switch to natural gas have long warned that the fuel is too volatile, price-wise, to be relied upon as a major source of baseload electricity generation. That’s true even now, when we’re in the midst of a natural gas glut so big, with prices generally so low, that natural gas drillers in many areas have simply given up. The cost of a thousand cubic feet of natural gas swung from $2.80 last spring to about $4.50 this January, thanks in part to additional demand from the power sector, but also to new demand from manufacturers and millions of homes that use the fuel to heat their homes. As the prices went up, utilities simply switched back to that old, boring, but stable coal.

But coal-bashers shouldn’t give up hope. In the short-term, natural gas prices should drop as temperatures rise this spring. Utilities will fire up that extra natural gas generating capacity that they’ve constructed over the past decade or so, and perhaps the cleaner-burning fuel will surpass coal in the electricity generating mix – at least for a month or two. In the long term, as more and more coal plants are retired, the utilities will lose the ability to quickly switch back to coal even when natural gas prices swing back upward, as they surely will, especially if the fuel’s use in transportation grows, or if the feds decide this summer to allow large-scale export of liquefied natural gas. Just this week, NV Energy became the most recent Western utility to announce it’s abandoning coal in favor of natural gas and renewables.

Meanwhile, the experience should provide a lesson to those who now are building the energy infrastructure that will be with us for the next several decades: If you’ve got a choice between building natural gas or renewable infrastructure, go with the latter. The intermittency hurdle with solar and wind is a substantial one, yes, but it’s surpassable, too. Large scale energy storage technology would pretty much erase the hurdle (if we can ever figure it out), and so-called “geographic smoothing,” where you combine renewable resources over a vast geographical area so that a wind farm in, say, Wyoming can back up a solar plant in California, would ease the need for huge natural gas peaking plants. Yes, that would require new transmission lines and a different way of doing business, but the same is true for a big buildup of natural gas.

Yes, there can be a symbiotic relationship between natural gas and renewables. The question is: Are we prepared to live with its offspring?

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.