Inside the war on coal

The war on coal is not just political rhetoric, or a paranoid fantasy concocted by rapacious polluters. It’s real and it’s relentless. Over the past five years, it has killed a coal-fired power plant every 10 days. It has quietly transformed the U.S. electric grid and the global climate debate.

The industry and its supporters use “war on coal” as shorthand for a ferocious assault by a hostile White House, but the real war on coal is not primarily an Obama war, or even a Washington war. It’s a guerrilla war. The front lines are not at the Environmental Protection Agency or the Supreme Court. If you want to see how the fossil fuel that once powered most of the country is being battered by enemy forces, you have to watch state and local hearings where utility commissions and other obscure governing bodies debate individual coal plants. You probably won’t find much drama. You’ll definitely find lawyers from the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign, the boots on the ground in the war on coal.

Beyond Coal is the most extensive, expensive and effective campaign in the Club’s 123-year history, and maybe the history of the environmental movement. It’s gone largely unnoticed amid the furor over the Keystone pipeline and President Barack Obama’s efforts to regulate carbon, but it’s helped retire more than one third of America’s coal plants since its launch in 2010, one dull hearing at a time. With a vast war chest donated by Michael Bloomberg, unlikely allies from the business world, and a strategy that relies more on economics than ecology, its team of nearly 200 litigators and organizers has won battles in the Midwestern and Appalachian coal belts, in the reddest of red states, in almost every state that burns coal.

“They’re sophisticated, they’re very active, and they’re better funded than we are,” says Mike Duncan, a former Republican National Committee chairman who now heads the industry-backed American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity. “I don’t like what they’re doing; we’re losing a lot of coal in this country. But they do show up.”

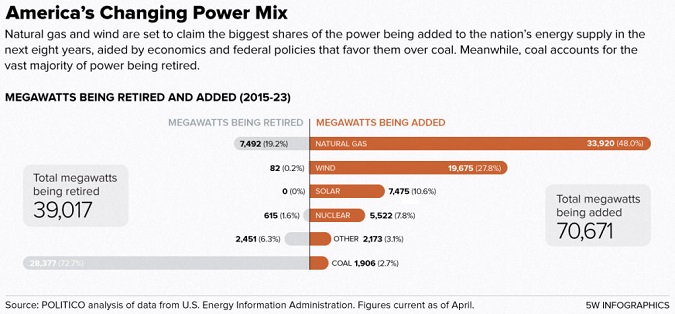

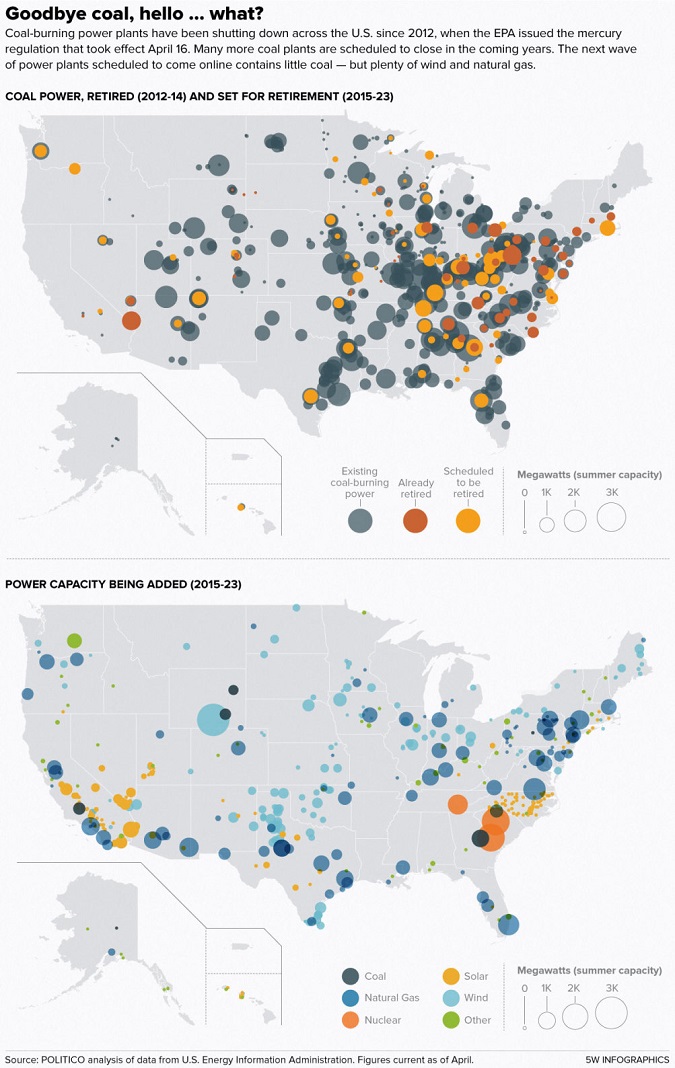

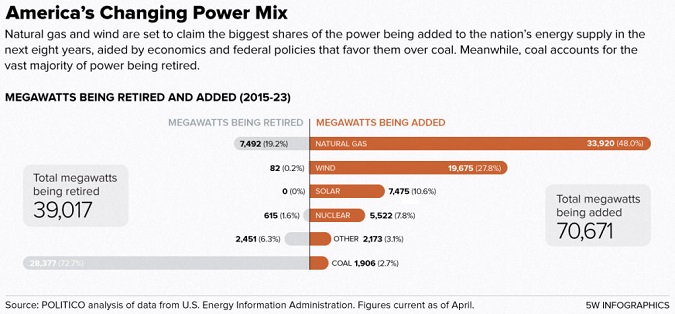

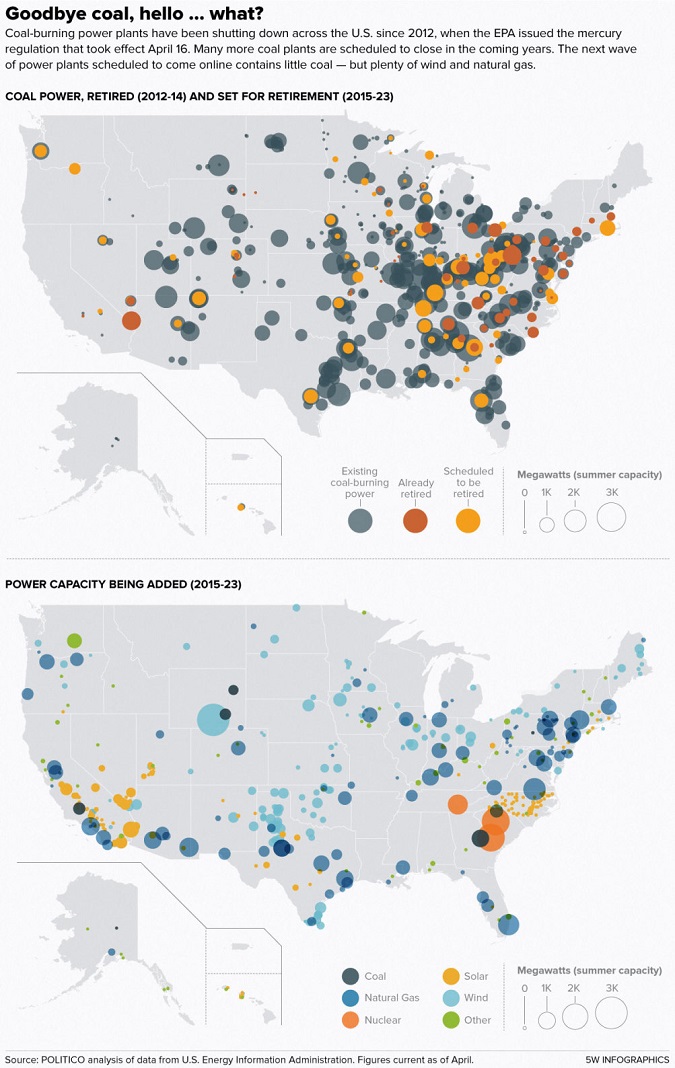

Coal still helps keep our lights on, generating nearly 40 percent of U.S. power. But it generated more than 50 percent just over a decade ago, and the big question now is how rapidly its decline will continue. Almost every watt of new generating capacity is coming from natural gas, wind or solar; the coal industry now employs fewer workers than the solar industry, which barely existed in 2010. Utilities no longer even bother to propose new coal plants to replace the old ones they retire. Coal industry stocks are tanking, and analysts are predicting a new wave of coal bankruptcies.

This is a big deal, because coal is America’s top source of greenhouse gases, and coal retirements are the main reason U.S. carbon emissions have declined 10 percent in a decade. Coal is also America’s top source of mercury, sulfur dioxide and other toxic air pollutants, so fewer coal plants also means less asthma and lung disease—not to mention fewer coal-ash spills and coal-mining disasters. The shift toward cleaner-burning gas and zero-emissions renewables is the most important change in our electricity mix in decades, and while Obama has been an ally in the war on coal—not always as aggressive an ally as the industry claims—the Sierra Club is in the trenches. The U.S. had 523 coal-fired power plants when Beyond Coal began targeting them; just last week, it celebrated the 190th retirement of its campaign in Asheville, N.C., culminating a three-year fight that had been featured in the climate documentary “Years of Living Dangerously.”

Beyond Coal isn’t the stereotypical Sierra Club campaign, tree-huggers shouting save-the-Earth slogans. Yes, it sometimes deploys its 2.4 million-member, grass-roots army to shutter plants with traditional not-in-my-back-yard organizing and right-to-breathe agitating. But it usually wins by arguing that ditching coal will save ratepayers money.

Behind that argument lies a revolution in the economics of power, changes few Americans think about when they flick their switches. Coal used to be the cheapest form of electricity by far, but it’s gotten pricier as it’s been forced to clean up more of its mess, while the costs of gas, wind and solar have plunged in recent years. Now retrofitting old coal plants with the pollution controls needed to comply with Obama’s limits on soot, sulfur and mercury is becoming cost-prohibitive—and the EPA is finalizing its new carbon rules as well as tougher ozone restrictions that should add to the burden. That’s why the Sierra Club finds itself in foxholes with big-box stores, manufacturers and other business interests, fighting coal upgrades that would jack up electricity bills, pushing for cheaper renewables and energy efficiency instead. In a case I watched in Oklahoma City, every stakeholder supported Beyond Coal’s push for a utility to buy more low-cost wind power—including a coalition of industrial customers that reportedly included a Koch Industries-owned paper mill.

“They’re not burning bras. They’re fighting dollar to dollar,” says attorney Jim Roth, who represented a group of hospitals on Beyond Coal’s side in the Oklahoma case. “They’ve become masters at bringing financial arguments to environmental questions.”

As the affordability case for coal has lost traction, the industry’s defenders have portrayed the war on coal as a war on reliability, an assault on 24-hour “baseload” plants that provide juice when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing. They ask how the Sierra Club expects America to run its refrigerators around the clock—since it also opposes nuclear power and has a separate Beyond Gas campaign. Duncan’s group started a Twitter meme warning that Americans could end up #ColdInTheDark, and even Bloomberg suggested to me in a recent interview that the Club’s leaders seem to want Americans to wear loincloths and live in caves.

In fact, neither the decline of coal, nor the boom in renewables has blacked out the grid, and Beyond Coal’s leaders are confident electricity markets can handle much more intermittent power. In any case, they see coal as the lowest-hanging fruit in the struggle to stabilize the climate, not only our dirtiest fossil fuel but the one with the cheapest alternatives. In the long run, combating global warming will depend a multitude of factors, from electric vehicles to carbon releases from deforestation to methane releases from belching cows, but for the next decade, our climate progress depends mostly on reducing our reliance on the black stuff. Coal retirements have enabled Obama to pledge U.S. emissions cuts of up to 28 percent by 2025, which has, in turn, enabled him to strike a climate deal with China and pursue a global deal later this year in Paris.

“We’ve found the secret sauce to making progress in unlikely places,” says Bruce Nilles, who leads Beyond Coal from the Club’s San Francisco headquarters. “And every time we beat the coal boys, people say: ‘Whoa. It can be done.’”

The Sierra Club can’t claim full credit for the coal bust. It didn’t ratchet down the prices of gas, wind and solar or enact the flurry of EPA rules ratcheting up the price of coal, although its lobbyists and lawyers have pushed hard for government support for renewables while fighting in court over just about every coal-related regulation. It didn’t produce the energy efficiency boom that has reined in electricity demand, either. Still, a Bloomberg Philanthropies analysis found that at least 40 percent of U.S. coal retirements could not have happened without Beyond Coal’s advocacy. The status quo wields a lot of power in the heavily regulated power sector, where economics and mathematics don’t always beat politics and inertia. The case for change keeps getting stronger, but someone has to make the case.

When Mary Anne Hitt, Beyond Coal’s national director, first visited Indianapolis to fight an inner-city plant, the headline in the Star was: “Beyond Coal’s Director Faces Tough Sell in Indiana.” But after two years of door-knocking, phone-banking and educating officials on the new realities of electricity, the Sierra Club and its local partners helped shut down the plant. Hitt has seen the same kind of miracle in Chicago, in Omaha, alongside a Paiute tribe reservation in Nevada, even in coal strongholds like Kentucky. It’s starting to feel more like a pattern than a miracle.

“David is fighting Goliath every day, and David keeps winning,” Hitt says.

Energy analysts have a way of making Goliath’s new underdog status seem inevitable. Then again, it wasn’t long ago that their burning question about the U.S. coal industry was not how fast it would go away, but how fast it would grow.

The story of coal is a rich vein in the American story, powering our industry, our railroads, our politics. For decades, the work of extracting coal after millions of years underground—so dangerous for some, so lucrative for others—was seen as God’s work. The alchemy of converting coal into valuable energy was seen as a fulfillment of America’s destiny to exploit nature for the benefit of mankind, even as the smog spewing out of coal smokestacks was seen as part of the dystopia of urban life.

These days, growing concerns about climate have heightened concerns about coal, which produces 75 percent of the power sector’s carbon, and more emissions than all our cars and trucks combined. But even at the dawn of the 21st century, the George W. Bush administration’s main concern about coal power and fossil energy in general was that the U.S. wasn’t producing enough of it. In 2001, an energy task force led by Dick Cheney, after a series of secret meetings with fossil-fuel executives, called for a new power-plant construction boom, warning that the alternative was a national reprise of the rolling blackouts that had just roiled California. Utilities quickly proposed about 200 new coal plants, and faced no organized national opposition. Coal plants have a useful lifespan of at least 40 years, so the U.S. was poised to lock in a new generation of dirty power. And all that new capacity was poised to destroy any incentive to develop clean wind or solar power.

That’s when the Sierra Club got into its first big coal fight over a proposed billion-dollar plant south of Chicago, a welcome-to-the-NFL episode. The Chicago area already had poor air quality—the coal plants around the Loop were known as the Ring of Fire—and local volunteers, led by an indefatigable German immigrant named Verena Owen, were desperate to block the project. Their cause seemed hopeless, but for Owen, who is now Beyond Coal’s lead volunteer, it was personal. Her best friend had struggled to breathe whenever the air was hazy and eventually died of lung disease, leaving behind a daughter in kindergarten. “I don’t know how many people we ended up saving, but I know one we didn’t,” Owen says.

The first time Nilles, at the time a lawyer for the Sierra Club’s Midwest office in Chicago, tried to attend a hearing about the plant, union members who supported the project came early and packed the hall while the Club was holding a news conference. Illinois regulators soon rubber-stamped the permit. Owen and Nilles can still recite the date and time of the news dump: Friday, Oct. 10, 2003, at 5:10 p.m., so the bureaucrats could ignore their calls and escape for the weekend. And the industry had an even easier time of it elsewhere. Nilles later reviewed the record for another billion-dollar plant that broke ground in Iowa about the same time, and discovered there hadn’t been a single public comment in opposition.

“Everything was going full speed in the wrong direction, and we had no capacity to fight,” he says. “We realized we needed a strategy. Fast.”

The strategy that Nilles devised was to fight every new plant from every conceivable environmental, economic and political angle. The Sierra Club began organizing boot camps to teach lawyers and volunteers around the region how to block coal permits. Demand for the seminars was so intense that, at one point, Nilles’ boss had to remind him that Texas was not part of the Midwest. But he figured Texans who breathed air and drank water had as much to lose from exposure to coal-fired pollutants as Midwesterners had. Some of the Club’s funders thought his fight-everything-everywhere approach was unrealistic during a national coal rush, but every proposed plant was in someone’s backyard, and the Club had members in every corner of the country. Nilles couldn’t imagine telling any of them their communities would have to be sacrificed for the greater tactical good.

Environmentalists have always been good at blocking stuff, and over the next few years, the kitchen-sink strategy produced some improbable victories. Nilles exploited threats to an endangered clover to delay the Chicago-area plant, and the utility eventually abandoned it. A local Sierra Club chapter stopped a massive plant in Kentucky coal country after a 63-day hearing, convincing regulators that the proposal had inadequate pollution controls, and that adequate controls would be exorbitant for ratepayers. These were shoestring crusades with expert witnesses crashing on the couches of volunteers, but the victories felt contagious, spreading hope to activists in other states who read about them on the Club’s coal listserv.

Meanwhile, the Sierra Club was canvassing its members to develop a new long-term strategic plan. To the surprise of then-Director Carl Pope, they overwhelmingly wanted climate and energy to be the top priority, a major shift for a group that had emphasized wilderness conservation since its creation by the legendary outdoorsman John Muir. At a meeting in Tucson in early 2006, the Club’s board voted to build the fledgling Midwestern anti-coal effort into a national campaign. Climate activists are often accused of wasting energy on symbolic movement-building efforts with relatively limited impact on emissions, like their crusades to stop Keystone and get universities to divest from fossil fuels. Beyond Coal’s leaders do oppose the pipeline and support the divestment movement, but the rationale for the campaign was all about hunting where the ducks are.

“It was existential necessity: Look how many coal plants they want to build. Look how much carbon they’d produce. Well, it’s game over if we don’t stop them,” Pope recalls. “If we were going to focus on climate, we had to focus on coal.”

In a bow to political realism, the initial goal was to make sure coal was “mined responsibly, burned cleanly and disposed of safely.” But the campaigners didn’t really believe coal could be burned cleanly. The original mouthful of a mission soon evolved to “Move Beyond Coal,” then just “Beyond Coal.” It was a much simpler message, helping to unite a variety of activists—working for specific neighborhoods, Indian tribes, mountains targeted by mining outfits, public health, environmental justice, clean energy, and the climate—against a common enemy. The Sierra Club would be the one constant presence in the war on coal, but it began partnering with more than 100 local, regional and national groups in its battles around the country.

The campaign was remarkably successful. Nilles and his team scoured every permit application for vulnerabilities and managed to block all but 30 of the 200 plants proposed in the Bush era. The nice thing about fighting new plants was that they didn’t exist yet, so it only took one deal breaker—too much smog in a high-smog area, too close to a national park, too expensive for ratepayers, whatever—to break a deal. Some of the plants that did get built still haunt Nilles, but those defeats did not doom the decarbonization of America. The game was not over.

By 2008, with the economy crashing and power demand slumping, utilities had stopped pushing new coal plants. That’s when Nilles began plotting to go after old ones—an even tougher challenge, but a vital one to avoid the game-over scenario. He had moved to the liberal college town of Madison, and he was amazed that an old coal plant a mile from his home still had no pollution controls; it was way dirtier than the new plants he was fighting around the country. The nation’s fleet of existing coal plants was still emitting nearly 2 billion tons of carbon and causing an estimated 13,000 premature deaths every year. It felt good to stop projects that would have increased those numbers, but Nilles wanted to use the Club’s newfound expertise to reduce them.

“It’s a lot easier to throw ourselves in front of bulldozers to stop something than it is to shut something down that’s already part of the community, paying taxes, generating power, providing jobs,” Nilles says. “But that’s where the emissions are.”

That was also the year Obama won the presidency, creating hope for stricter EPA regulation of sulfur, soot and ozone, plus the first-ever regulations of mercury, coal ash and carbon. As difficult as it would be to kill plants that had been operating for decades—two-thirds of the coal fleet predated the Clean Air Act of 1970—Nilles thought the combination of top-down rules from Washington and bottom-up pressure at state and local hearings could force utilities to confront investment decisions they had been delaying all those decades. Most utilities would need approval from their financial and environmental regulators before they could install expensive pollution controls. And while the utilities might be happy to charge their customers tens of millions of dollars for upgrades in order to comply with one new rule—plus a tidy profit they’re usually guaranteed for capital improvements—utility commissions might not let them start down that road if they faced hundreds of millions of dollars in additional compliance costs from rules still to come.

Once again, the campaign produced some inspiring early wins, including the retirement of that antiquated plant near Nilles in Madison. He also filed a lawsuit against his alma mater, the University of Wisconsin, to get it off coal. The Club quickly found that when it could stop investor-owned utilities from getting a blank check to charge ratepayers for coal upgrades, they would usually shut down the plants rather than risk shareholder dollars. That was even true in coal country, where homeowners, businesses and regulators were just as allergic to pricey upgrades—and utilities were just as reluctant to foot the bill themselves. As Nilles’ new deputy, Hitt, a West Virginia activist who had spent years trying to stop mining companies from blowing up mountains in Appalachia, found she could do more to protect the mountains by shutting down the plants that used their coal.

Beyond Coal had grown from three staffers to a 15-state operation, but it still lacked the scale to fight 523 plants all over the country. It needed to get a lot bigger. That’s when the combative billionaire who has financed his own wars on guns, tobacco and Big Gulps took an interest in the war on coal.

Beyond Coal’s pivotal moment came at a meeting in Gracie Mansion about, of all things, education reform. Michael Bloomberg, the Wall Street savant-turned media mogul-turned New York City mayor, was looking for a new outlet for his private philanthropy. It quickly became clear that education reform would not be that outlet.

“It was a terrible meeting in every way, and Mike was angry,” recalls his longtime adviser, Kevin Sheekey. “I said: ‘Look, if you don’t like this idea, that’s fine. We’ll bring you another.’ He said: ‘No, I want another now.’”

As it happened, Sheekey had just eaten lunch with Carl Pope, who was starting a $50 million fundraising drive to expand Beyond Coal’s staff to 45 states. The cap-and-trade plan that Obama supported to cut carbon emissions had stalled in Congress, and the carbon tax that Bloomberg supported was going nowhere as well. Washington was gridlocked. But Pope had explained to Sheekey that shutting down coal plants at the state and local level could do even more for the climate—and have a huge impact on public health issues close to his boss’s heart.

“That’s a good idea,” Bloomberg told Sheekey. “We’ll just give Carl a check for the $50 million. Tell him to stop fundraising and get to work.”

Bloomberg had never thought of himself as a Sierra Club kind of guy. But he saw coal as a killer, as well as the main threat to the climate, and the Club was in the field doing something about it. His only demand was a more analytical approach to the war on coal, with measurable deliverables, complex predictive models for vulnerable plants, and KPI—Key Performance Indicators, as Pope later learned.

“The Sierra Club had never heard of KPI,” Pope says. “We just had a gut instinct for what would work. The mayor said: ‘Oh, no, no. This will be data-driven.’”

On a sweltering day in July 2011, Bloomberg announced his gift to the Club on a boat he had chartered on the Potomac River, in front of a 63-year-old coal plant he had always noticed on flights into Washington. He saw it as a perfect illustration of the city’s inability to get anything done.

“You’d think the politicians would at least care about the air they breathe themselves!” Bloomberg marveled to me in a recent interview.

That plant on the Potomac is now closed. So is the Massachusetts plant that Mitt Romney once said “kills people,” a line Obama actually used against him in coal-state campaign ads in 2012. So are all of Chicago’s plants, as Mayor Rahm Emanuel boasted in his first campaign ad in 2015. Overall, the 190 plants that U.S. utilities have agreed to retire will eliminate about one fourth of America’s coal-fired capacity, a total of 79 gigawatts. And for every watt of coal capacity they’re taking out of commission, they’ve already installed a watt of wind or solar capacity. The Clean Air Task Force estimate of coal-fired premature deaths is down to about 7,500 a year, a decrease of 5,500 since Beyond Coal went national. And Bloomberg’s early support has helped attract more than $100 million from top foundations and wealthy individuals like the Silicon Valley billionaire Tom Steyer, the climate movement’s top political donor.

“It’s a reminder that you can do a lot with no help from Congress,” Bloomberg says. “I just wish we could point out the specific people who were saved.”

To coal backers, Beyond Coal is pure urban elitist lunacy, the kind of nightmare you get when a nanny-state mayor from New York hooks up with eco-radicals from San Francisco and a liberal president in Washington. Republican Senator James Inhofe of Oklahoma—chairman of the Environment and Public Works Committee, author of “The Greatest Hoax,” thrower of a Senate-floor snowball designed to highlight the folly of global-warming alarmism—told me it’s hard to believe some Americans actually want to keep our abundant energy resources in the ground.

“It’s a war on all fossil fuels, and coal is the No. 1 target,” Inhofe says. “You got a president who doesn’t care how many jobs it costs, and rich people who don’t care how much money they spend. They can do a lot of damage.”

I got to watch the war in Inhofe’s state, and the damage wasn’t getting done the way Inhofe imagined. The job creators were siding with the environmentalists. Economics was the most powerful weapon in the Sierra Club’s arsenal.

At a dry hearing in a drab courtroom in Oklahoma City, a methodical Beyond Coal attorney named Kristin Henry, whose bio identifies her as “one of the few environmentalists who would never be caught wearing Birkenstocks,” was pinning down an Oklahoma Gas & Electric executive with a barrage of wouldn’t-you-agrees, isn’t-it-trues, and would-it-be-fair-to-say’s. The power company was out of compliance with a federal air-quality rule called “regional haze,” so it was offering to convert one of its two coal plants into a natural gas plant. Henry knew she couldn’t stop that. But OG&E also wanted to install massive new scrubbers on the other plant so it could keep burning coal for decades to come. Henry was determined to stop that.

In the 90 minutes Henry spent cross-examining OG&E’s Joseph Rowlett in early March, she didn’t ask a single question about climate or public health. She focused exclusively on OG&E’s request for the largest rate increase in state history, a 15 percent hike to finance the utility’s $700 million compliance plan. Through her deadpan, leading questions, she portrayed OG&E as a company desperate to get its customers to foot the bill to prop up an inefficient plant, pursuing retrofits it would never consider if its own shareholders had to swallow the costs, operating in a dream world where regional haze was coal’s only challenge. At one point, she got Rowlett to admit his calculations assumed there would be no additional coal regulations for the next thirty years, even though the EPA intends to finalize at least four new coal regulations this year alone.

“Isn’t it true you’re assuming zero over the next 30 years?” Henry asked.

Rowlett paused a few seconds. “That’s right,” he replied.

The Sierra Club, even though it didn’t sound much like the Sierra Club, was clearly in hostile political territory. Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt, a conservative Republican who has spearheaded a national campaign to protect fossil fuels from legal challenges, had joined OG&E in fighting the EPA haze rule all the way to the Supreme Court. Now he was supposed to be representing consumers at the OG&E hearing before the Oklahoma Corporation Commission, but he hadn’t even filed a brief about the record rate hike. “That’s unheard of,” one commission official told me. Pruitt didn’t attend the hearing, either—the day it began, he was in Tulsa with Mike Huckabee raising money for his PAC—but one of his deputies who did attend occasionally raised objections when OG&E witnesses were asked uncomfortable questions.

But if the political deck seemed stacked against the Sierra Club, Henry held the economic cards. In Oklahoma, coal imported from Wyoming now costs more per kilowatt hour than the abundant gas under the ground or the wind that famously comes sweeping down the plain. In another recent haze case, the Sierra Club cut a deal requiring Oklahoma’s other major utility to phase out its only coal plant and buy 200 megawatts of wind—and the bids came in so low, the utility ended up buying 600 megawatts of wind. That’s why Walmart, the hospital group and the coalition of industrial ratepayers all supported Beyond Coal’s push for more wind in the OG&E case. Cheap electricity has a way of scrambling political alliances.

Henry and the lawyers for OG&E’s corporate customers formed a kind of tag team, taking turns blasting the company for refusing to even study new wind power. They repeatedly pointed out that in-state competitors as well as Florida and New Mexico utilities were buying Oklahoma wind for just 2 cents per kilowatt hour, even cheaper than coal without pollution controls, while OG&E hadn’t purchased new wind in four years—even though its ads boasted about its commitment to wind. When its witnesses claimed their transmission lines were too congested to add new wind, Henry produced internal documents suggesting the congestion could be fixed for about 3 percent of the cost of the new coal scrubbers. As she pointed out, other Oklahoma utilities have much higher percentages of wind power on their systems.

Closing coal plants can sound radical, but Henry framed it for the Republican utility commissioners as the conservative response to EPA rules, avoiding the risk of “stranded” investments in outdated plants that might have to be shut down anyway. The most economical way to meet haze limits, she suggested, would be to stop burning the coal that causes the haze. Al Armendariz, who was Obama’s Dallas-based regional EPA administrator and is now Beyond Coal’s Austin-based regional representative, says the Club’s victories in states like Georgia, Mississippi and Kentucky have helped normalize the idea of abandoning coal in Oklahoma.

“We get respect because of our track record,” Armendariz says. “When we say a utility isn’t acting prudently, people can’t just dismiss us as ‘Oh, of course the Sierra Club says that.’ They see how we keep winning. They see these big industrial customers agreeing with us. Then they look at the numbers and see we’re right.”

Still, there’s no denying the war on coal is leading America into uncharted territory. The Sierra Club wants to eliminate all coal power by 2030, but what will replace it? Wind and solar, despite their rapid Obama-era growth, still make up just 5 percent of U.S. power capacity. And while technologies to store renewable energy (such as Tesla’s newly announced battery packs) are getting cheaper, they’re still a rounding error on the grid. Beyond Coal’s leaders are content to push cleaner power and let utilities figure out how to deliver it, but as OG&E Vice President Paul Renfrow told me: “That’s easy for them to say. We have to keep the lights on.”

Inhofe thinks the Sierra Club is simply obsessed with rooting out fossil fuels, citing “the guy who wants to crucify people” as an example of its extremism. He meant Armendariz, who left the EPA after he was caught on tape suggesting that harsh sanctions for law-breaking oil and gas companies could scare others into compliance, just as public crucifixions helped keep the peace in Roman times.

“The Sierra Club wants to stop coal now?” Inhofe asked. “You’ll see, they’ll be after gas next.”

Long-term, he’s right. While the Club accepted some donations from natural gas interests under Pope, it is now formally committed to eliminating gas as well as coal by 2030, and it has helped block new gas plants in cities like Austin and Carlsbad, California. After its victory last week in Asheville, Beyond Coal vowed to keep fighting to overturn Duke Energy’s decision to build a new gas plant to replace its 50-year-old coal plant. Even Bloomberg thinks the Club’s opposition to the fracking boom that has helped replace so much domestic coal with domestic gas is silly.

That said, Beyond Coal’s leaders, including Armendariz, understand that Beyond Gas is more aspirational than practical for now. They deeply prefer renewables to gas, but they almost as deeply prefer gas to coal. In Oklahoma City, Henry grilled OG&E witnesses about why they wanted to spend $500 million on scrubbers for coal boilers that could be retrofitted to burn gas for just $70 million. She shredded the implausible assumptions OG&E had made in its economic models to make scrubbing coal look cheaper than converting to gas, forcing one witness to admit gas prices were already 25 percent lower than his low-cost scenario. I sat in on one friendly lunch the Club’s legal team had with lawyers for a Conoco Phillips front group; they all hoped to move OG&E beyond coal, and gas is clearly part of the short-term solution.

“We want to be principled but pragmatic,” says Sierra Club Executive Director Michael Brune, who stopped the Club’s gas-industry gifts when he took over in 2010. “We’ve wrestled with this, and there’s a definite disagreement with Bloomberg. We don’t see gas as an environmental fix. But we acknowledge that we still need some gas.”

Coal is different. Bloomberg calls it “a dead man walking.” When he made his initial gift to the Sierra Club, the goal was to secure the retirements of one third of the coal fleet by 2015. The Club is only slightly behind schedule, and in April, Bloomberg came to Washington to announce another $30 million donation, with a new goal of retirement announcements for half of the fleet by 2017. “We’re doubling down on an incredibly successful strategy,” Bloomberg said.

The campaign’s leaders believe coal has already passed a tipping point toward oblivion. Coal giants like Alpha Natural Resources, Arch Coal and Walter Energy are struggling to stay afloat. Just last week, in addition to the retirement announcement for the Asheville plant—as well as another for a Milwaukee plant that wasn’t official enough for Beyond Coal to count as #191—the insurance giant AXA announced that it will sell off more than $500 million worth of coal investments, the largest financial institution to flee the space to date, while the EPA announced it was closing a loophole that allowed virtually unlimited emissions from malfunctioning coal plants, a response to yet another Sierra Club lawsuit. And the more dirty plants get shut down, the more residents near other dirty plants are asking: Why not ours?

It’s hard to change the status quo, no matter how compelling the economic logic. Beyond Coal does not just deploy data. It organizes rallies and petitions and float-ins on kayaks; it shames utility executives on billboards and airplane banners; it mobilizes its members to show up at boring hearings where showing up can make a difference. If the Oklahoma City case displayed the war on coal as a numerical dispute, another hearing I watched south of Detroit was more like a street fight.

River Rouge is a depressed community at the city’s edge, a blightscape of boarded-up bungalows, overgrown lots and pawn shops. There’s no grocery store and virtually no medical services, but there is a nice little park where kids play at the playground and adults fish in the Detroit River. Unfortunately, the park smells like rotten eggs, thanks to sulfur dioxide from a DTE Energy coal plant overlooking the playground. Michigan health officials have called this area “the epicenter of the state’s asthma burden.” The fish aren’t safe to eat, either, though people eat them.

“It’s just an unhealthy situation,” says Alisha Winters, a local resident and mother of seven children, two with asthma. “They figure they can get away with dumping on us.”

The EPA has called out this area’s elevated sulfur dioxide levels, and last year Republican Governor Rick Snyder’s administration floated a compliance plan that would have required DTE to upgrade the coal-fired River Rouge Power Plant or (more likely) close it. But DTE proposed an alternative plan with no costly upgrades, and the state quietly accepted it. The Sierra Club has been mobilizing opposition ever since, drawing an unusual coalition of local whites, African-Americans, Latinos and Arab-Americans—as well as a busload of white liberals from Ann Arbor—for an environmental hearing in mid-March. The hearing had to be moved from City Hall to a school auditorium to accommodate the groundswell of protests, a far cry from that Chicago-area hearing over a decade ago where the Sierra Club got frozen out.

“We’re getting people to cross borders, physical and imaginary,” says Rhonda Anderson, a sharecropper’s daughter who is now an organizer for Beyond Coal.

If the Oklahoma City hearing was financial, the River Rouge hearing was political, a multiracial show of force in “I Love Clean Air” T-shirts. Every speaker opposed the DTE plan, including an Indian-American medical student, an Arab-American law student, an African-American asthma educator, a Latina anti-poverty activist and a white nun. Ebony Elmore, a child care provider who lives a block from the plant, talked about her four siblings and three nieces with asthma, as well as her two parents with pulmonary disease. I happened to ask Democratic Rep. Debbie Dingell, who was watching the testimony from the side of the hall, why she was there, just as another resident started telling a story about an 11-year-old local girl who died because she couldn’t get to her inhaler in time.

“That’s why I’m here,” Dingell whispered.

A few days later, Governor Snyder—whose top campaign supporters included one Michael Bloomberg—announced a new effort to cut Michigan’s reliance on coal. That would have been a huge political burden for Snyder if he had run for president in a GOP primary, where “anti-coal” will be an epithet like “anti-gun” or “anti-freedom,” but he decided not to run, and coal is becoming a huge economic burden for his industrial state.

The already frenetic national pace of plant retirements will have to double for Beyond Coal to meet its 2017 goal, but utilities will face daunting investment decisions over the next two years. The EPA recently settled a sulfur lawsuit with the Sierra Club that could replicate the River Rouge dilemma across the nation. The agency has also imposed regional haze plans that already are replicating the Oklahoma dilemma in Arizona, Arkansas and Texas. Today, Beyond Coal has more than 100 legal cases pending over power supply. Meanwhile, it’s pursuing a new strategy on the power demand side, pushing blue states like Oregon to stop importing coal-fired electricity, which could shutter plants in red states like Montana. Even inside Texas, the Club has worked with relatively progressive cities like Austin, San Antonio and El Paso to replace their coal power with renewables.

Beyond Coal is also continuing to lobby and litigate in Washington, pushing Obama to drop his “all-of-the-above” approach to energy and formally enlist in the war on coal. Obama has not been as maniacally anti-coal as the industry suggests, punting on ozone rules in his first term to avoid alienating voters in Ohio, issuing relatively weak restrictions on coal ash, taking a lenient approach to mining on public land, floating carbon rules with mild targets for the most coal-reliant states. Still, when you add up all he’s done and all he’s doing, you get a tremendously uncertain regulatory environment. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky—whose wife, Elaine Chao, recently quit the Bloomberg Philanthropies board over coal—has urged states to defy the Clean Power Plan, but utilities with fiduciary responsibilities don’t engage in much civil disobedience. They have already shut down dozens of plants to comply with mercury rules the Supreme Court could still strike down, and they’re starting to think about carbon, too.

Some coal advocates still hold out hope that the decline can be reversed if Republicans can win the presidency and keep Congress. “We’ve got a Congress that’s sympathetic, but we’ve still got a bureaucracy running amok,” says Mike Duncan, the RNC chairman-turned-coal advocate. “That will play in 2016. Obviously, anytime you elect a leader, it’s important to this industry.”

If the EPA stands down under the next president, the pace of retirements could slow. But it probably won’t stop. The trends are too strong. Nilles recently met with leaders of the utility Southern Company, which has slashed its dependence on coal in half over the past five years. Its executives rejected his vision of a coal-free America by 2030, but some of them suggested 2050 could be realistic. In any case, the Sierra Club won a lot of coal fights during the pro-coal Bush administration, because they were ultimately local fights over local air.

The fights also have a global context. The Earth is already getting hotter, and the death of American coal would not avert a climate catastrophe if the rest of the world did not follow our lead. But the decline of American coal emissions will help U.S. negotiators insist that other countries do their part in the global negotiations in Paris. And while critics of climate action often grumble that it would be foolish for the U.S. to make sacrifices when China is still building a new coal plant every week, that’s no longer true. China actually decreased its coal use last year, and is shuttering all four plants in smog-shrouded Beijing. The trends killing coal in America—cheap gas, wind and solar; more energy efficiency; stricter regulations—are trending abroad as well. Cash-strapped U.S. mining firms are desperate to solve their domestic problems by selling more coal in foreign markets, but the Sierra Club has helped lead the fight to block six proposed coal export terminals in the Pacific Northwest, which will help keep even more coal in the ground.

There will be no formal surrender in the war on coal, no battleship treaty to mark the end. But Beyond Coal’s leaders believe they can finish most of their work setting the U.S. electric sector on a greener path over the next five years. The next phase of the war on carbon would be to try to electrify everything else—cars and trains that use oil-derived gasoline and diesel, as well as homes and businesses that rely on natural gas and heating oil. Nilles hopes power companies like OG&E and DTE that Beyond Coal has spent the last decade fighting with—but then cutting deals with—can become allies in Phase Two. And allies will be vital, because if King Coal seems like a rich and powerful enemy, it’s a pushover compared to Big Oil.

“Once we’ve taken out coal, we’ll need to take on oil, and who better to help than our new friends in the utility sector who can make money from electrification?” Nilles says with a grin. “It’s a long fight. This is how we win.”

The industry and its supporters use “war on coal” as shorthand for a ferocious assault by a hostile White House, but the real war on coal is not primarily an Obama war, or even a Washington war. It’s a guerrilla war. The front lines are not at the Environmental Protection Agency or the Supreme Court. If you want to see how the fossil fuel that once powered most of the country is being battered by enemy forces, you have to watch state and local hearings where utility commissions and other obscure governing bodies debate individual coal plants. You probably won’t find much drama. You’ll definitely find lawyers from the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign, the boots on the ground in the war on coal.

Beyond Coal is the most extensive, expensive and effective campaign in the Club’s 123-year history, and maybe the history of the environmental movement. It’s gone largely unnoticed amid the furor over the Keystone pipeline and President Barack Obama’s efforts to regulate carbon, but it’s helped retire more than one third of America’s coal plants since its launch in 2010, one dull hearing at a time. With a vast war chest donated by Michael Bloomberg, unlikely allies from the business world, and a strategy that relies more on economics than ecology, its team of nearly 200 litigators and organizers has won battles in the Midwestern and Appalachian coal belts, in the reddest of red states, in almost every state that burns coal.

“They’re sophisticated, they’re very active, and they’re better funded than we are,” says Mike Duncan, a former Republican National Committee chairman who now heads the industry-backed American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity. “I don’t like what they’re doing; we’re losing a lot of coal in this country. But they do show up.”

Coal still helps keep our lights on, generating nearly 40 percent of U.S. power. But it generated more than 50 percent just over a decade ago, and the big question now is how rapidly its decline will continue. Almost every watt of new generating capacity is coming from natural gas, wind or solar; the coal industry now employs fewer workers than the solar industry, which barely existed in 2010. Utilities no longer even bother to propose new coal plants to replace the old ones they retire. Coal industry stocks are tanking, and analysts are predicting a new wave of coal bankruptcies.

This is a big deal, because coal is America’s top source of greenhouse gases, and coal retirements are the main reason U.S. carbon emissions have declined 10 percent in a decade. Coal is also America’s top source of mercury, sulfur dioxide and other toxic air pollutants, so fewer coal plants also means less asthma and lung disease—not to mention fewer coal-ash spills and coal-mining disasters. The shift toward cleaner-burning gas and zero-emissions renewables is the most important change in our electricity mix in decades, and while Obama has been an ally in the war on coal—not always as aggressive an ally as the industry claims—the Sierra Club is in the trenches. The U.S. had 523 coal-fired power plants when Beyond Coal began targeting them; just last week, it celebrated the 190th retirement of its campaign in Asheville, N.C., culminating a three-year fight that had been featured in the climate documentary “Years of Living Dangerously.”

Beyond Coal isn’t the stereotypical Sierra Club campaign, tree-huggers shouting save-the-Earth slogans. Yes, it sometimes deploys its 2.4 million-member, grass-roots army to shutter plants with traditional not-in-my-back-yard organizing and right-to-breathe agitating. But it usually wins by arguing that ditching coal will save ratepayers money.

Behind that argument lies a revolution in the economics of power, changes few Americans think about when they flick their switches. Coal used to be the cheapest form of electricity by far, but it’s gotten pricier as it’s been forced to clean up more of its mess, while the costs of gas, wind and solar have plunged in recent years. Now retrofitting old coal plants with the pollution controls needed to comply with Obama’s limits on soot, sulfur and mercury is becoming cost-prohibitive—and the EPA is finalizing its new carbon rules as well as tougher ozone restrictions that should add to the burden. That’s why the Sierra Club finds itself in foxholes with big-box stores, manufacturers and other business interests, fighting coal upgrades that would jack up electricity bills, pushing for cheaper renewables and energy efficiency instead. In a case I watched in Oklahoma City, every stakeholder supported Beyond Coal’s push for a utility to buy more low-cost wind power—including a coalition of industrial customers that reportedly included a Koch Industries-owned paper mill.

“They’re not burning bras. They’re fighting dollar to dollar,” says attorney Jim Roth, who represented a group of hospitals on Beyond Coal’s side in the Oklahoma case. “They’ve become masters at bringing financial arguments to environmental questions.”

As the affordability case for coal has lost traction, the industry’s defenders have portrayed the war on coal as a war on reliability, an assault on 24-hour “baseload” plants that provide juice when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing. They ask how the Sierra Club expects America to run its refrigerators around the clock—since it also opposes nuclear power and has a separate Beyond Gas campaign. Duncan’s group started a Twitter meme warning that Americans could end up #ColdInTheDark, and even Bloomberg suggested to me in a recent interview that the Club’s leaders seem to want Americans to wear loincloths and live in caves.

In fact, neither the decline of coal, nor the boom in renewables has blacked out the grid, and Beyond Coal’s leaders are confident electricity markets can handle much more intermittent power. In any case, they see coal as the lowest-hanging fruit in the struggle to stabilize the climate, not only our dirtiest fossil fuel but the one with the cheapest alternatives. In the long run, combating global warming will depend a multitude of factors, from electric vehicles to carbon releases from deforestation to methane releases from belching cows, but for the next decade, our climate progress depends mostly on reducing our reliance on the black stuff. Coal retirements have enabled Obama to pledge U.S. emissions cuts of up to 28 percent by 2025, which has, in turn, enabled him to strike a climate deal with China and pursue a global deal later this year in Paris.

“We’ve found the secret sauce to making progress in unlikely places,” says Bruce Nilles, who leads Beyond Coal from the Club’s San Francisco headquarters. “And every time we beat the coal boys, people say: ‘Whoa. It can be done.’”

The Sierra Club can’t claim full credit for the coal bust. It didn’t ratchet down the prices of gas, wind and solar or enact the flurry of EPA rules ratcheting up the price of coal, although its lobbyists and lawyers have pushed hard for government support for renewables while fighting in court over just about every coal-related regulation. It didn’t produce the energy efficiency boom that has reined in electricity demand, either. Still, a Bloomberg Philanthropies analysis found that at least 40 percent of U.S. coal retirements could not have happened without Beyond Coal’s advocacy. The status quo wields a lot of power in the heavily regulated power sector, where economics and mathematics don’t always beat politics and inertia. The case for change keeps getting stronger, but someone has to make the case.

When Mary Anne Hitt, Beyond Coal’s national director, first visited Indianapolis to fight an inner-city plant, the headline in the Star was: “Beyond Coal’s Director Faces Tough Sell in Indiana.” But after two years of door-knocking, phone-banking and educating officials on the new realities of electricity, the Sierra Club and its local partners helped shut down the plant. Hitt has seen the same kind of miracle in Chicago, in Omaha, alongside a Paiute tribe reservation in Nevada, even in coal strongholds like Kentucky. It’s starting to feel more like a pattern than a miracle.

“David is fighting Goliath every day, and David keeps winning,” Hitt says.

Energy analysts have a way of making Goliath’s new underdog status seem inevitable. Then again, it wasn’t long ago that their burning question about the U.S. coal industry was not how fast it would go away, but how fast it would grow.

The story of coal is a rich vein in the American story, powering our industry, our railroads, our politics. For decades, the work of extracting coal after millions of years underground—so dangerous for some, so lucrative for others—was seen as God’s work. The alchemy of converting coal into valuable energy was seen as a fulfillment of America’s destiny to exploit nature for the benefit of mankind, even as the smog spewing out of coal smokestacks was seen as part of the dystopia of urban life.

These days, growing concerns about climate have heightened concerns about coal, which produces 75 percent of the power sector’s carbon, and more emissions than all our cars and trucks combined. But even at the dawn of the 21st century, the George W. Bush administration’s main concern about coal power and fossil energy in general was that the U.S. wasn’t producing enough of it. In 2001, an energy task force led by Dick Cheney, after a series of secret meetings with fossil-fuel executives, called for a new power-plant construction boom, warning that the alternative was a national reprise of the rolling blackouts that had just roiled California. Utilities quickly proposed about 200 new coal plants, and faced no organized national opposition. Coal plants have a useful lifespan of at least 40 years, so the U.S. was poised to lock in a new generation of dirty power. And all that new capacity was poised to destroy any incentive to develop clean wind or solar power.

That’s when the Sierra Club got into its first big coal fight over a proposed billion-dollar plant south of Chicago, a welcome-to-the-NFL episode. The Chicago area already had poor air quality—the coal plants around the Loop were known as the Ring of Fire—and local volunteers, led by an indefatigable German immigrant named Verena Owen, were desperate to block the project. Their cause seemed hopeless, but for Owen, who is now Beyond Coal’s lead volunteer, it was personal. Her best friend had struggled to breathe whenever the air was hazy and eventually died of lung disease, leaving behind a daughter in kindergarten. “I don’t know how many people we ended up saving, but I know one we didn’t,” Owen says.

The first time Nilles, at the time a lawyer for the Sierra Club’s Midwest office in Chicago, tried to attend a hearing about the plant, union members who supported the project came early and packed the hall while the Club was holding a news conference. Illinois regulators soon rubber-stamped the permit. Owen and Nilles can still recite the date and time of the news dump: Friday, Oct. 10, 2003, at 5:10 p.m., so the bureaucrats could ignore their calls and escape for the weekend. And the industry had an even easier time of it elsewhere. Nilles later reviewed the record for another billion-dollar plant that broke ground in Iowa about the same time, and discovered there hadn’t been a single public comment in opposition.

“Everything was going full speed in the wrong direction, and we had no capacity to fight,” he says. “We realized we needed a strategy. Fast.”

The strategy that Nilles devised was to fight every new plant from every conceivable environmental, economic and political angle. The Sierra Club began organizing boot camps to teach lawyers and volunteers around the region how to block coal permits. Demand for the seminars was so intense that, at one point, Nilles’ boss had to remind him that Texas was not part of the Midwest. But he figured Texans who breathed air and drank water had as much to lose from exposure to coal-fired pollutants as Midwesterners had. Some of the Club’s funders thought his fight-everything-everywhere approach was unrealistic during a national coal rush, but every proposed plant was in someone’s backyard, and the Club had members in every corner of the country. Nilles couldn’t imagine telling any of them their communities would have to be sacrificed for the greater tactical good.

Environmentalists have always been good at blocking stuff, and over the next few years, the kitchen-sink strategy produced some improbable victories. Nilles exploited threats to an endangered clover to delay the Chicago-area plant, and the utility eventually abandoned it. A local Sierra Club chapter stopped a massive plant in Kentucky coal country after a 63-day hearing, convincing regulators that the proposal had inadequate pollution controls, and that adequate controls would be exorbitant for ratepayers. These were shoestring crusades with expert witnesses crashing on the couches of volunteers, but the victories felt contagious, spreading hope to activists in other states who read about them on the Club’s coal listserv.

Meanwhile, the Sierra Club was canvassing its members to develop a new long-term strategic plan. To the surprise of then-Director Carl Pope, they overwhelmingly wanted climate and energy to be the top priority, a major shift for a group that had emphasized wilderness conservation since its creation by the legendary outdoorsman John Muir. At a meeting in Tucson in early 2006, the Club’s board voted to build the fledgling Midwestern anti-coal effort into a national campaign. Climate activists are often accused of wasting energy on symbolic movement-building efforts with relatively limited impact on emissions, like their crusades to stop Keystone and get universities to divest from fossil fuels. Beyond Coal’s leaders do oppose the pipeline and support the divestment movement, but the rationale for the campaign was all about hunting where the ducks are.

“It was existential necessity: Look how many coal plants they want to build. Look how much carbon they’d produce. Well, it’s game over if we don’t stop them,” Pope recalls. “If we were going to focus on climate, we had to focus on coal.”

In a bow to political realism, the initial goal was to make sure coal was “mined responsibly, burned cleanly and disposed of safely.” But the campaigners didn’t really believe coal could be burned cleanly. The original mouthful of a mission soon evolved to “Move Beyond Coal,” then just “Beyond Coal.” It was a much simpler message, helping to unite a variety of activists—working for specific neighborhoods, Indian tribes, mountains targeted by mining outfits, public health, environmental justice, clean energy, and the climate—against a common enemy. The Sierra Club would be the one constant presence in the war on coal, but it began partnering with more than 100 local, regional and national groups in its battles around the country.

The campaign was remarkably successful. Nilles and his team scoured every permit application for vulnerabilities and managed to block all but 30 of the 200 plants proposed in the Bush era. The nice thing about fighting new plants was that they didn’t exist yet, so it only took one deal breaker—too much smog in a high-smog area, too close to a national park, too expensive for ratepayers, whatever—to break a deal. Some of the plants that did get built still haunt Nilles, but those defeats did not doom the decarbonization of America. The game was not over.

By 2008, with the economy crashing and power demand slumping, utilities had stopped pushing new coal plants. That’s when Nilles began plotting to go after old ones—an even tougher challenge, but a vital one to avoid the game-over scenario. He had moved to the liberal college town of Madison, and he was amazed that an old coal plant a mile from his home still had no pollution controls; it was way dirtier than the new plants he was fighting around the country. The nation’s fleet of existing coal plants was still emitting nearly 2 billion tons of carbon and causing an estimated 13,000 premature deaths every year. It felt good to stop projects that would have increased those numbers, but Nilles wanted to use the Club’s newfound expertise to reduce them.

“It’s a lot easier to throw ourselves in front of bulldozers to stop something than it is to shut something down that’s already part of the community, paying taxes, generating power, providing jobs,” Nilles says. “But that’s where the emissions are.”

That was also the year Obama won the presidency, creating hope for stricter EPA regulation of sulfur, soot and ozone, plus the first-ever regulations of mercury, coal ash and carbon. As difficult as it would be to kill plants that had been operating for decades—two-thirds of the coal fleet predated the Clean Air Act of 1970—Nilles thought the combination of top-down rules from Washington and bottom-up pressure at state and local hearings could force utilities to confront investment decisions they had been delaying all those decades. Most utilities would need approval from their financial and environmental regulators before they could install expensive pollution controls. And while the utilities might be happy to charge their customers tens of millions of dollars for upgrades in order to comply with one new rule—plus a tidy profit they’re usually guaranteed for capital improvements—utility commissions might not let them start down that road if they faced hundreds of millions of dollars in additional compliance costs from rules still to come.

Once again, the campaign produced some inspiring early wins, including the retirement of that antiquated plant near Nilles in Madison. He also filed a lawsuit against his alma mater, the University of Wisconsin, to get it off coal. The Club quickly found that when it could stop investor-owned utilities from getting a blank check to charge ratepayers for coal upgrades, they would usually shut down the plants rather than risk shareholder dollars. That was even true in coal country, where homeowners, businesses and regulators were just as allergic to pricey upgrades—and utilities were just as reluctant to foot the bill themselves. As Nilles’ new deputy, Hitt, a West Virginia activist who had spent years trying to stop mining companies from blowing up mountains in Appalachia, found she could do more to protect the mountains by shutting down the plants that used their coal.

Beyond Coal had grown from three staffers to a 15-state operation, but it still lacked the scale to fight 523 plants all over the country. It needed to get a lot bigger. That’s when the combative billionaire who has financed his own wars on guns, tobacco and Big Gulps took an interest in the war on coal.

Beyond Coal’s pivotal moment came at a meeting in Gracie Mansion about, of all things, education reform. Michael Bloomberg, the Wall Street savant-turned media mogul-turned New York City mayor, was looking for a new outlet for his private philanthropy. It quickly became clear that education reform would not be that outlet.

“It was a terrible meeting in every way, and Mike was angry,” recalls his longtime adviser, Kevin Sheekey. “I said: ‘Look, if you don’t like this idea, that’s fine. We’ll bring you another.’ He said: ‘No, I want another now.’”

As it happened, Sheekey had just eaten lunch with Carl Pope, who was starting a $50 million fundraising drive to expand Beyond Coal’s staff to 45 states. The cap-and-trade plan that Obama supported to cut carbon emissions had stalled in Congress, and the carbon tax that Bloomberg supported was going nowhere as well. Washington was gridlocked. But Pope had explained to Sheekey that shutting down coal plants at the state and local level could do even more for the climate—and have a huge impact on public health issues close to his boss’s heart.

“That’s a good idea,” Bloomberg told Sheekey. “We’ll just give Carl a check for the $50 million. Tell him to stop fundraising and get to work.”

Bloomberg had never thought of himself as a Sierra Club kind of guy. But he saw coal as a killer, as well as the main threat to the climate, and the Club was in the field doing something about it. His only demand was a more analytical approach to the war on coal, with measurable deliverables, complex predictive models for vulnerable plants, and KPI—Key Performance Indicators, as Pope later learned.

“The Sierra Club had never heard of KPI,” Pope says. “We just had a gut instinct for what would work. The mayor said: ‘Oh, no, no. This will be data-driven.’”

On a sweltering day in July 2011, Bloomberg announced his gift to the Club on a boat he had chartered on the Potomac River, in front of a 63-year-old coal plant he had always noticed on flights into Washington. He saw it as a perfect illustration of the city’s inability to get anything done.

“You’d think the politicians would at least care about the air they breathe themselves!” Bloomberg marveled to me in a recent interview.

That plant on the Potomac is now closed. So is the Massachusetts plant that Mitt Romney once said “kills people,” a line Obama actually used against him in coal-state campaign ads in 2012. So are all of Chicago’s plants, as Mayor Rahm Emanuel boasted in his first campaign ad in 2015. Overall, the 190 plants that U.S. utilities have agreed to retire will eliminate about one fourth of America’s coal-fired capacity, a total of 79 gigawatts. And for every watt of coal capacity they’re taking out of commission, they’ve already installed a watt of wind or solar capacity. The Clean Air Task Force estimate of coal-fired premature deaths is down to about 7,500 a year, a decrease of 5,500 since Beyond Coal went national. And Bloomberg’s early support has helped attract more than $100 million from top foundations and wealthy individuals like the Silicon Valley billionaire Tom Steyer, the climate movement’s top political donor.

“It’s a reminder that you can do a lot with no help from Congress,” Bloomberg says. “I just wish we could point out the specific people who were saved.”

To coal backers, Beyond Coal is pure urban elitist lunacy, the kind of nightmare you get when a nanny-state mayor from New York hooks up with eco-radicals from San Francisco and a liberal president in Washington. Republican Senator James Inhofe of Oklahoma—chairman of the Environment and Public Works Committee, author of “The Greatest Hoax,” thrower of a Senate-floor snowball designed to highlight the folly of global-warming alarmism—told me it’s hard to believe some Americans actually want to keep our abundant energy resources in the ground.

“It’s a war on all fossil fuels, and coal is the No. 1 target,” Inhofe says. “You got a president who doesn’t care how many jobs it costs, and rich people who don’t care how much money they spend. They can do a lot of damage.”

I got to watch the war in Inhofe’s state, and the damage wasn’t getting done the way Inhofe imagined. The job creators were siding with the environmentalists. Economics was the most powerful weapon in the Sierra Club’s arsenal.

At a dry hearing in a drab courtroom in Oklahoma City, a methodical Beyond Coal attorney named Kristin Henry, whose bio identifies her as “one of the few environmentalists who would never be caught wearing Birkenstocks,” was pinning down an Oklahoma Gas & Electric executive with a barrage of wouldn’t-you-agrees, isn’t-it-trues, and would-it-be-fair-to-say’s. The power company was out of compliance with a federal air-quality rule called “regional haze,” so it was offering to convert one of its two coal plants into a natural gas plant. Henry knew she couldn’t stop that. But OG&E also wanted to install massive new scrubbers on the other plant so it could keep burning coal for decades to come. Henry was determined to stop that.

In the 90 minutes Henry spent cross-examining OG&E’s Joseph Rowlett in early March, she didn’t ask a single question about climate or public health. She focused exclusively on OG&E’s request for the largest rate increase in state history, a 15 percent hike to finance the utility’s $700 million compliance plan. Through her deadpan, leading questions, she portrayed OG&E as a company desperate to get its customers to foot the bill to prop up an inefficient plant, pursuing retrofits it would never consider if its own shareholders had to swallow the costs, operating in a dream world where regional haze was coal’s only challenge. At one point, she got Rowlett to admit his calculations assumed there would be no additional coal regulations for the next thirty years, even though the EPA intends to finalize at least four new coal regulations this year alone.

“Isn’t it true you’re assuming zero over the next 30 years?” Henry asked.

Rowlett paused a few seconds. “That’s right,” he replied.

The Sierra Club, even though it didn’t sound much like the Sierra Club, was clearly in hostile political territory. Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt, a conservative Republican who has spearheaded a national campaign to protect fossil fuels from legal challenges, had joined OG&E in fighting the EPA haze rule all the way to the Supreme Court. Now he was supposed to be representing consumers at the OG&E hearing before the Oklahoma Corporation Commission, but he hadn’t even filed a brief about the record rate hike. “That’s unheard of,” one commission official told me. Pruitt didn’t attend the hearing, either—the day it began, he was in Tulsa with Mike Huckabee raising money for his PAC—but one of his deputies who did attend occasionally raised objections when OG&E witnesses were asked uncomfortable questions.

But if the political deck seemed stacked against the Sierra Club, Henry held the economic cards. In Oklahoma, coal imported from Wyoming now costs more per kilowatt hour than the abundant gas under the ground or the wind that famously comes sweeping down the plain. In another recent haze case, the Sierra Club cut a deal requiring Oklahoma’s other major utility to phase out its only coal plant and buy 200 megawatts of wind—and the bids came in so low, the utility ended up buying 600 megawatts of wind. That’s why Walmart, the hospital group and the coalition of industrial ratepayers all supported Beyond Coal’s push for more wind in the OG&E case. Cheap electricity has a way of scrambling political alliances.

Henry and the lawyers for OG&E’s corporate customers formed a kind of tag team, taking turns blasting the company for refusing to even study new wind power. They repeatedly pointed out that in-state competitors as well as Florida and New Mexico utilities were buying Oklahoma wind for just 2 cents per kilowatt hour, even cheaper than coal without pollution controls, while OG&E hadn’t purchased new wind in four years—even though its ads boasted about its commitment to wind. When its witnesses claimed their transmission lines were too congested to add new wind, Henry produced internal documents suggesting the congestion could be fixed for about 3 percent of the cost of the new coal scrubbers. As she pointed out, other Oklahoma utilities have much higher percentages of wind power on their systems.

Closing coal plants can sound radical, but Henry framed it for the Republican utility commissioners as the conservative response to EPA rules, avoiding the risk of “stranded” investments in outdated plants that might have to be shut down anyway. The most economical way to meet haze limits, she suggested, would be to stop burning the coal that causes the haze. Al Armendariz, who was Obama’s Dallas-based regional EPA administrator and is now Beyond Coal’s Austin-based regional representative, says the Club’s victories in states like Georgia, Mississippi and Kentucky have helped normalize the idea of abandoning coal in Oklahoma.

“We get respect because of our track record,” Armendariz says. “When we say a utility isn’t acting prudently, people can’t just dismiss us as ‘Oh, of course the Sierra Club says that.’ They see how we keep winning. They see these big industrial customers agreeing with us. Then they look at the numbers and see we’re right.”

Still, there’s no denying the war on coal is leading America into uncharted territory. The Sierra Club wants to eliminate all coal power by 2030, but what will replace it? Wind and solar, despite their rapid Obama-era growth, still make up just 5 percent of U.S. power capacity. And while technologies to store renewable energy (such as Tesla’s newly announced battery packs) are getting cheaper, they’re still a rounding error on the grid. Beyond Coal’s leaders are content to push cleaner power and let utilities figure out how to deliver it, but as OG&E Vice President Paul Renfrow told me: “That’s easy for them to say. We have to keep the lights on.”

Inhofe thinks the Sierra Club is simply obsessed with rooting out fossil fuels, citing “the guy who wants to crucify people” as an example of its extremism. He meant Armendariz, who left the EPA after he was caught on tape suggesting that harsh sanctions for law-breaking oil and gas companies could scare others into compliance, just as public crucifixions helped keep the peace in Roman times.

“The Sierra Club wants to stop coal now?” Inhofe asked. “You’ll see, they’ll be after gas next.”

Long-term, he’s right. While the Club accepted some donations from natural gas interests under Pope, it is now formally committed to eliminating gas as well as coal by 2030, and it has helped block new gas plants in cities like Austin and Carlsbad, California. After its victory last week in Asheville, Beyond Coal vowed to keep fighting to overturn Duke Energy’s decision to build a new gas plant to replace its 50-year-old coal plant. Even Bloomberg thinks the Club’s opposition to the fracking boom that has helped replace so much domestic coal with domestic gas is silly.

That said, Beyond Coal’s leaders, including Armendariz, understand that Beyond Gas is more aspirational than practical for now. They deeply prefer renewables to gas, but they almost as deeply prefer gas to coal. In Oklahoma City, Henry grilled OG&E witnesses about why they wanted to spend $500 million on scrubbers for coal boilers that could be retrofitted to burn gas for just $70 million. She shredded the implausible assumptions OG&E had made in its economic models to make scrubbing coal look cheaper than converting to gas, forcing one witness to admit gas prices were already 25 percent lower than his low-cost scenario. I sat in on one friendly lunch the Club’s legal team had with lawyers for a Conoco Phillips front group; they all hoped to move OG&E beyond coal, and gas is clearly part of the short-term solution.

“We want to be principled but pragmatic,” says Sierra Club Executive Director Michael Brune, who stopped the Club’s gas-industry gifts when he took over in 2010. “We’ve wrestled with this, and there’s a definite disagreement with Bloomberg. We don’t see gas as an environmental fix. But we acknowledge that we still need some gas.”

Coal is different. Bloomberg calls it “a dead man walking.” When he made his initial gift to the Sierra Club, the goal was to secure the retirements of one third of the coal fleet by 2015. The Club is only slightly behind schedule, and in April, Bloomberg came to Washington to announce another $30 million donation, with a new goal of retirement announcements for half of the fleet by 2017. “We’re doubling down on an incredibly successful strategy,” Bloomberg said.

The campaign’s leaders believe coal has already passed a tipping point toward oblivion. Coal giants like Alpha Natural Resources, Arch Coal and Walter Energy are struggling to stay afloat. Just last week, in addition to the retirement announcement for the Asheville plant—as well as another for a Milwaukee plant that wasn’t official enough for Beyond Coal to count as #191—the insurance giant AXA announced that it will sell off more than $500 million worth of coal investments, the largest financial institution to flee the space to date, while the EPA announced it was closing a loophole that allowed virtually unlimited emissions from malfunctioning coal plants, a response to yet another Sierra Club lawsuit. And the more dirty plants get shut down, the more residents near other dirty plants are asking: Why not ours?

It’s hard to change the status quo, no matter how compelling the economic logic. Beyond Coal does not just deploy data. It organizes rallies and petitions and float-ins on kayaks; it shames utility executives on billboards and airplane banners; it mobilizes its members to show up at boring hearings where showing up can make a difference. If the Oklahoma City case displayed the war on coal as a numerical dispute, another hearing I watched south of Detroit was more like a street fight.

River Rouge is a depressed community at the city’s edge, a blightscape of boarded-up bungalows, overgrown lots and pawn shops. There’s no grocery store and virtually no medical services, but there is a nice little park where kids play at the playground and adults fish in the Detroit River. Unfortunately, the park smells like rotten eggs, thanks to sulfur dioxide from a DTE Energy coal plant overlooking the playground. Michigan health officials have called this area “the epicenter of the state’s asthma burden.” The fish aren’t safe to eat, either, though people eat them.

“It’s just an unhealthy situation,” says Alisha Winters, a local resident and mother of seven children, two with asthma. “They figure they can get away with dumping on us.”

The EPA has called out this area’s elevated sulfur dioxide levels, and last year Republican Governor Rick Snyder’s administration floated a compliance plan that would have required DTE to upgrade the coal-fired River Rouge Power Plant or (more likely) close it. But DTE proposed an alternative plan with no costly upgrades, and the state quietly accepted it. The Sierra Club has been mobilizing opposition ever since, drawing an unusual coalition of local whites, African-Americans, Latinos and Arab-Americans—as well as a busload of white liberals from Ann Arbor—for an environmental hearing in mid-March. The hearing had to be moved from City Hall to a school auditorium to accommodate the groundswell of protests, a far cry from that Chicago-area hearing over a decade ago where the Sierra Club got frozen out.

“We’re getting people to cross borders, physical and imaginary,” says Rhonda Anderson, a sharecropper’s daughter who is now an organizer for Beyond Coal.

If the Oklahoma City hearing was financial, the River Rouge hearing was political, a multiracial show of force in “I Love Clean Air” T-shirts. Every speaker opposed the DTE plan, including an Indian-American medical student, an Arab-American law student, an African-American asthma educator, a Latina anti-poverty activist and a white nun. Ebony Elmore, a child care provider who lives a block from the plant, talked about her four siblings and three nieces with asthma, as well as her two parents with pulmonary disease. I happened to ask Democratic Rep. Debbie Dingell, who was watching the testimony from the side of the hall, why she was there, just as another resident started telling a story about an 11-year-old local girl who died because she couldn’t get to her inhaler in time.

“That’s why I’m here,” Dingell whispered.

A few days later, Governor Snyder—whose top campaign supporters included one Michael Bloomberg—announced a new effort to cut Michigan’s reliance on coal. That would have been a huge political burden for Snyder if he had run for president in a GOP primary, where “anti-coal” will be an epithet like “anti-gun” or “anti-freedom,” but he decided not to run, and coal is becoming a huge economic burden for his industrial state.

The already frenetic national pace of plant retirements will have to double for Beyond Coal to meet its 2017 goal, but utilities will face daunting investment decisions over the next two years. The EPA recently settled a sulfur lawsuit with the Sierra Club that could replicate the River Rouge dilemma across the nation. The agency has also imposed regional haze plans that already are replicating the Oklahoma dilemma in Arizona, Arkansas and Texas. Today, Beyond Coal has more than 100 legal cases pending over power supply. Meanwhile, it’s pursuing a new strategy on the power demand side, pushing blue states like Oregon to stop importing coal-fired electricity, which could shutter plants in red states like Montana. Even inside Texas, the Club has worked with relatively progressive cities like Austin, San Antonio and El Paso to replace their coal power with renewables.

Beyond Coal is also continuing to lobby and litigate in Washington, pushing Obama to drop his “all-of-the-above” approach to energy and formally enlist in the war on coal. Obama has not been as maniacally anti-coal as the industry suggests, punting on ozone rules in his first term to avoid alienating voters in Ohio, issuing relatively weak restrictions on coal ash, taking a lenient approach to mining on public land, floating carbon rules with mild targets for the most coal-reliant states. Still, when you add up all he’s done and all he’s doing, you get a tremendously uncertain regulatory environment. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky—whose wife, Elaine Chao, recently quit the Bloomberg Philanthropies board over coal—has urged states to defy the Clean Power Plan, but utilities with fiduciary responsibilities don’t engage in much civil disobedience. They have already shut down dozens of plants to comply with mercury rules the Supreme Court could still strike down, and they’re starting to think about carbon, too.

Some coal advocates still hold out hope that the decline can be reversed if Republicans can win the presidency and keep Congress. “We’ve got a Congress that’s sympathetic, but we’ve still got a bureaucracy running amok,” says Mike Duncan, the RNC chairman-turned-coal advocate. “That will play in 2016. Obviously, anytime you elect a leader, it’s important to this industry.”