Indigenous coalition goes head-to-head against oil giants to build Alberta carbon capture complex

A group of Indigenous communities in northeast Alberta are competing with big name oil and gas companies to secure the rights to construct and operate the first large-scale, regional carbon capture and storage facility in the province.

A group of Indigenous communities in northeast Alberta are competing with big name oil and gas companies to secure the rights to construct and operate the first large-scale, regional carbon capture and storage facility in the province.

Bids are due on Feb. 1 to build the first of what the Alberta government hopes will be many carbon capture hubs throughout the province — each one likely costing billions of dollars and requiring several years to develop and build.

Prominent oil and gas companies, including Shell, Suncor, and TC Energy, are among those who have also expressed interest for several months in being chosen by the Alberta government to build and operate such a facility. The Alberta government has picked an area known as the Industrial Heartland, northeast of Edmonton, as the location for the first proposed centre as the area has a concentration of heavy-emitting facilities that produce fuel, fertilizer and chemicals. The government will announce the winning proposal next month.

Chief Greg Desjarlais of the Frog Lake First Nation, located about 200 km east of Edmonton, describes it as a historic opportunity.

“We have to leave Mother Earth in a state where our kids and grandkids can flourish and have fresh water and breathe fresh air. So I think that’s the big sales pitch that we need to look at. And secondly, is economic reconciliation with the First Nations,” he said.

There is a general feeling by many First Nations and Métis communities in the province that they haven’t benefited from oil and gas development nearly as much as they should have, said Desjarlais, and this is an opportunity to begin rectifying the situation.

Stiff competition

Desjarlais said his group is likely an underdog in the completion, but he’s hopeful there could be an advantage in being the only Indigenous-led proposal.

“We don’t know what’s going to happen with the Heartland. There’s a lot of big players,” he said.

If their bid is unsuccessful, Desjarlais said they are open to working with companies. However, he makes it abundantly clear that his group wants an ownership stake, instead of signing a deal providing benefits to Indigenous communities, like jobs.

“This is our traditional territory and we’re looking for prosperity, revenue sharing, and of course, an ownership in the project,” he said.

As part of the bid process, the provincial government lists several criteria for how proposals will be judged, including financing, commercial strategy, risks, and project design. Benefits to Indigenous communities is also one of the criteria, which the government lists possible examples including “skills training, employment, business development, community investment, private sector partnerships, and major project participation.”

Earlier this month, about a dozen First Nations and Métis communities met in-person and virtually to discuss the proposed carbon capture project. The majority of those Indigenous leaders are from the Cold Lake region, located about 300 km northeast of Edmonton.

“That’s exciting to see. All nations working together at one time. It’s a long time coming,” said Chief Roger Marten of Cold Lake First Nation.

Increased attention on carbon capture

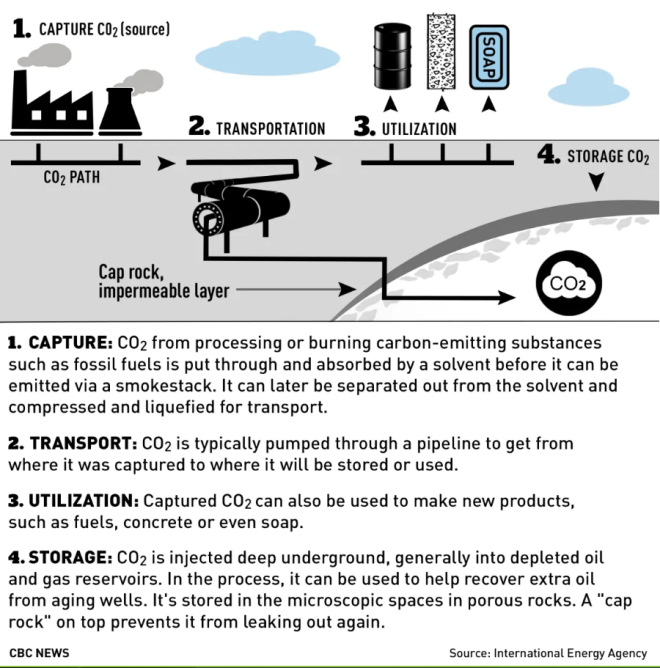

The Alberta government’s process to permit the develop of carbon capture facilities comes at a time of increased excitement and concern about the technology. Proponents see carbon capture as one of the tools to lower emissions from various industrial sectors that are contributing to climate change and difficult to decarbonize.

Meanwhile, critics often suggest the investment would be better spent on renewable or other low-carbon forms of energy. They also say carbon capture facilities could create perverse incentives, which could make it more difficult for the world to transition away from fossil fuels.

Currently, the federal government is developing an investment tax credit to incentivize more CCS construction to help reduce the country’s emissions.

A few carbon capture projects already exist in Alberta, but projects constructed in the future are expected to be much larger.

Alberta’s new hub system will not include carbon capture projects called enhanced oil recovery or EOR, where captured CO2 is used to help extract more crude from underground.

In addition to the Industrial Heartland bid, the group of Indigenous communities is also in talks with six oilsands companies that are proposing a carbon capture project in the Cold Lake area. Carbon emissions would be transported south by pipeline from the Fort McMurray region.

The companies make up the Oil Sands Pathways to Net Zero initiative, which wants to capture and sequester 8.5 million tonnes of carbon emissions every year by the end of the decade. In 2019, the oil sands produced about 83 million tonnes of emissions, according to Environment and Climate Change Canada, and rose 26 per cent between 2000 and 2019.

“It’s going to impact the First Nations again, just like oil and gas have impacted First Nations over the years in a negative way, primarily,” said Joe Dion, former Chief to the Kehewin Cree Nation and CEO of Frog Lake Energy Resources.

“But this time, we’re going to turn it over on its heels and make sure that First Nations and Métis will benefit,” he said.

A spokesperson with the Pathways oilsands group said discussions with communities are at a very early stage.

Dion is also part of the Western Indigenous Pipeline Group, which is one of three Indigenous-led organizations trying to purchase the Trans Mountain oil pipeline project from the federal government.

A carbon capture project in northeast Alberta could reduce the emissions associated with producing the oil that would move through Trans Mountain, Dion said.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.