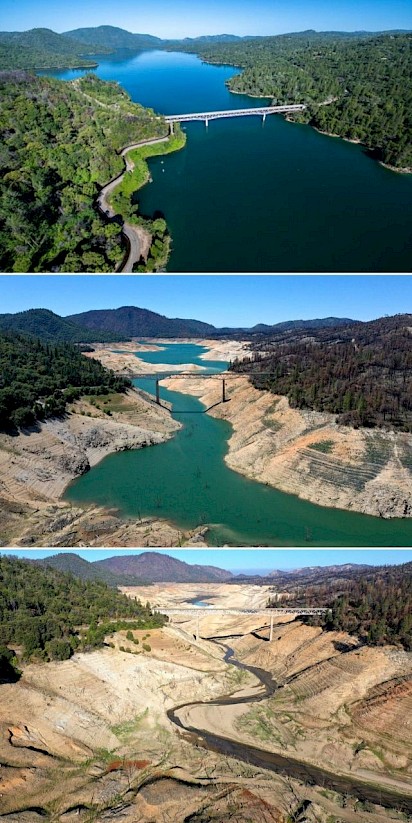

In drought-stricken West, officials weigh emergency actions

Federal officials say it may be necessary to reduce water deliveries to users on the Colorado River to prevent the shutdown of a huge dam that supplies hydropower to some 5 million customers across the U.S. West.

Federal officials say it may be necessary to reduce water deliveries to users on the Colorado River to prevent the shutdown of a huge dam that supplies hydropower to some 5 million customers across the U.S. West.

Officials had hoped snowmelt would buoy Lake Powell on the Arizona-Utah border to ensure its dam could continue to supply power. But snow is already melting, and hotter-than-normal temperatures and prolonged drought are further shrinking the lake.

The Interior Department has proposed holding back water in the lake to maintain Glen Canyon Dam’s ability to generate electricity amid what it said were the driest conditions in the region in more than 1,200 years.

“The best available science indicates that the effects of climate change will continue to adversely impact the basin,” Tanya Trujillo, the Interior’s assistant secretary for water and science wrote to seven states in the basin Friday.

Trujillo asked for feedback on the proposal to keep 480,000 acre-feet of water in Lake Powell — enough water to serve about 1 million U.S. households. She stressed that operating the dam below 3,490 feet (1,063 meters), considered its minimum power pool, is uncharted territory and would lead to even more uncertainty for the western electrical grid and water deliveries to states and Mexico downstream.

In the Colorado River basin, Glen Canyon Dam is the mammoth of power production, delivering electricity to about 5 million customers in seven states — Arizona, Colorado, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. As Lake Powell falls, the dam becomes less efficient. At 3,490 feet, it can’t produce power.

If levels were to fall below that mark, the 7,500 residents in the city at the lake, Page, and the adjacent Navajo community of LeChee would have no access to drinking water.

The Pacific Northwest, and the Rio Grande Valley in New Mexico and Texas are facing similar strains on water supplies.

Lake Powell fell below 3,525 feet (1,075 meters) for the first time ever last month, a level that concerned worried water managers. Federal data shows it will dip even further, in the most probable scenario, before rebounding above the level next spring.

If power production ceases at Glen Canyon Dam, customers that include cities, rural electric cooperatives and tribal utilities would be forced to seek more expensive options. The loss also would complicate western grid operations since hydropower is a relatively flexible renewable energy source that can be easily turned up or down, experts say.

“We’re in crisis management, and health and human safety issues, including production of hydropower, are taking precedence,” said Jack Schmidt, director of the center for Colorado River Studies at Utah State University. “Concepts like, ‘Are we going to get our water back’ just may not even be relevant anymore.”

The potential impacts to lower basin states that could see their water supplies reduced — California, Nevada and Arizona — aren’t yet known. But the Interior’s move is a display of the wide-ranging functions of Lake Powell and Glen Canyon Dam, and the need to quickly pivot to confront climate change.

Lake Powell serves as the barometer for the river’s health in the upper basin, and Lake Mead has that job in the lower basin. Both were last full in the year 2000 but have declined to one-fourth and one-third of their capacity, respectively, as drought tightened its grip on the region.

Water managers in the basin states — Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, New Mexico and Colorado — are evaluating the proposal. The Interior Department has set an April 22 deadline for feedback.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.