Hydrogen highway inches closer

California is inching tantalizingly closer to the birth of a new automotive industry based on hydrogen.

Fuel cell vehicles — electric cars that run on hydrogen — will be popping up this year and next near new clusters of fueling stations in and around San Francisco, Los Angeles and Orange County.

San Diego will get one hydrogen station next year as a lifeline to visitors from Orange County and beyond, part of a scaled back expansion strategy.

Under Gov. Jerry Brown, California is striving to get 1.5 million zero emission vehicles on the road by 2025 to reduce health threatening air pollution and greenhouse gases. Regulators and major automakers see a supporting if not starring role for fuel cell vehicles, the only alternative to battery-electric vehicles that also has no tailpipe pollution.

The state has committed $110 million so far to underwrite new hydrogen fueling stations, and set aside $20 million a year going forward. An effort to reduce the cost and length of time for construction is being led by Sandia National Laboratories and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

The intricate effort has detractors within the environmental community who worry hydrogen production could remain tethered to fossil fuels. Cheap natural gas is used for 95 percent of U.S. hydrogen.

A convenient network of fueling stations was first promised a decade ago — coined as California’s “hydrogen highway” — but foundered as engineers and economists struggled with cost-efficient solutions to producing and delivering hydrogen to vehicles.

The new strategy aims to contain costs by building small clusters of hydrogen stations to provide day-to-day convenience, with a few connector and destination fueling points to accommodate longer trips. State officials say as few as 100 strategically located stations, enough to support 18,000 vehicles, might be the tipping point for a self-sustaining refueling network that can compete with gasoline.

It is still unclear whether even a well-timed rollout of fuel stations and vehicles can entice Californians.

Hyundai has begun leasing a family-sized SUV for $499 a month, including a $3,000 down payment. The deal includes unlimited hydrogen refueling. Next year, Toyota plans to start selling a Prius-like hydrogen sedan, but has not disclosed a price in the U.S. In Japan, the price was announced at just under $70,000.

Battery powered vehicles range from $29,000 for the Nissan Leaf to $71,000 or more for a luxury Tesla Model S.

In California, fuel cell cars come with a state-funded rebate of $5,000, and up to $15,000 in certain low-income communities, according to Brett Williams, senior program manager for electric vehicles at the Center for Sustainable Energy, which administers state clean-vehicle rebate programs for California and Massachusetts. Fewer than 100 rebates have been claimed so far.

One additional perk: Fuel cell cars can ride in the express carpool lane with the driver traveling alone.

“The cars are really quite good at this point but the infrastructure has remained the Achilles’ heel,” he said.

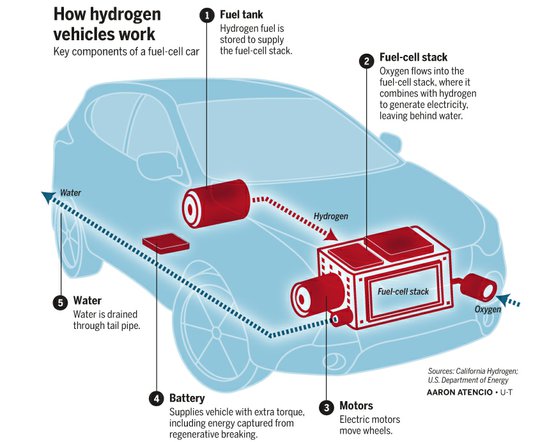

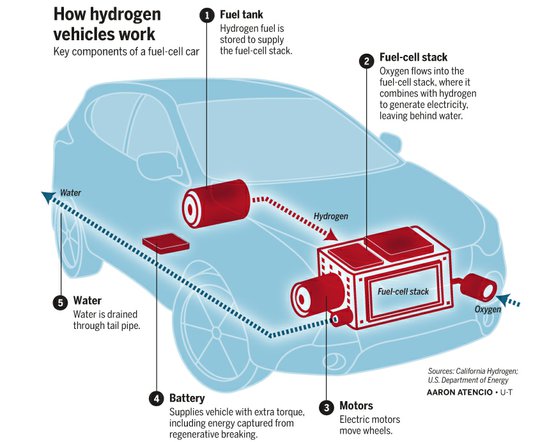

Fuel cells vehicles convert hydrogen to electricity using a chemical reaction that leaves behind only a trickle of water.

Unlike plug-ins, hydrogen-electric cars can drive for some 300 miles straight and refuel in a matter of minutes. Fuel cells can propel bigger family cars and trucks, the kind many Americans still are not willing to give up.

“For people who want a larger car, who want more of a similar experience in terms of range and refueling to the gasoline cars that they are driving today, battery-electric cars aren’t there,” said Catherine Dunwoody, chief of the fuel cell program at the California Air Resources Board. “Some people say they will be there. I think it would be risky to bet on that, given the advancement we need” on reducing pollution and greenhouse emission linked to climate change.

San Diego has been identified as an important potential sales market for fuel cell vehicles.

“Initially it’s a destination station, but it very quickly becomes its own cluster” for refueling stations, Dunwoody said.

Most hydrogen, used for hydrogenating food products and refining gasoline, currently comes from a process that combines steam and natural gas and does emit greenhouse gases.

Hydrogen supplied to California drivers must be certified as one-third renewable — substituting nonrenewable natural gas with methane captured from landfills and sewage treatment facilities. Two of the new California fueling points will provide 100 percent renewable hydrogen.

Emissions-free hydrogen production — using renewable such as solar energy to separate hydrogen from water through electrolysis — remains prohibitively expensive, a problem aggravated by cheap, plentiful U.S. natural gas. The equation may not change for decades.

Based on that panorama and advances in battery-electric cars, a vocal group of experts view investments in hydrogen infrastructure as unwise.

The loudest critical voice may be Tesla Motors founder Elon Musk, as he steers public support behind Tesla’s battery-electric vehicles.

Tam Hunt, a renewable energy policy consultant and blogger at Community Renewable Solutions in Santa Barbara, is among those questioning whether public policies supporting fuel cell vehicles really helps with the transition away from fossil fuels.

As long as hydrogen is tied to natural gas, benefits have to be weighed against the environmental toll of fracking techniques for extracting natural gas, Hunt argues. So-called green hydrogen still faces the problem of wasted energy from converting renewable electricity to hydrogen and back again in a car, he explained in a recent blog post.

“As hydrogen is increasingly produced from renewable electricity, it makes far more sense to use that electricity directly in battery-electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles due to the large conversion losses from making hydrogen with electricity.”

California is not alone in its embrace of fuel cell vehicles. Japan, South Korea,

German and England also are building their first hydrogen fueling clusters, with a combination of public and private investment.

The first direct retail sales of hydrogen in California are likely just months away, as the state Division of Measurement Standards completes enforceable guidelines for dispensing hydrogen by the kilogram.

The gradual opening of the hydrogen highway has enthusiasts delighted by new possibilities.

General Motors officials envision a fuel cell car that may some day be parked and plugged into a house to function as a backup 25 kilowatt generator. Eventually, surplus solar and wind power from the electric grid might be diverted to producing hydrogen — effectively storing green energy in a bottle.

Hydrogen currently used to refine gasoline could very well go directly into the vehicle fuel tanks of the future, said Scott Samuelsen, an engineering professor at the National Fuel Cell Research Center at University of California Irvine.

Like California policy makers, he too says the monopoly of gasoline and diesel cars will not be broken by battery-electric vehicles alone.

“It’s not expected that the battery will displace all of the gasoline vehicles and that’s where the hydrogen vehicle fits in,” he said. “As time goes on, I think the public will realize that both of these technologies are needed and desired — the electric vehicle for the shorter trips and the hydrogen for the longer trips.”

Fuel cell vehicles — electric cars that run on hydrogen — will be popping up this year and next near new clusters of fueling stations in and around San Francisco, Los Angeles and Orange County.

San Diego will get one hydrogen station next year as a lifeline to visitors from Orange County and beyond, part of a scaled back expansion strategy.

Under Gov. Jerry Brown, California is striving to get 1.5 million zero emission vehicles on the road by 2025 to reduce health threatening air pollution and greenhouse gases. Regulators and major automakers see a supporting if not starring role for fuel cell vehicles, the only alternative to battery-electric vehicles that also has no tailpipe pollution.

The state has committed $110 million so far to underwrite new hydrogen fueling stations, and set aside $20 million a year going forward. An effort to reduce the cost and length of time for construction is being led by Sandia National Laboratories and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

The intricate effort has detractors within the environmental community who worry hydrogen production could remain tethered to fossil fuels. Cheap natural gas is used for 95 percent of U.S. hydrogen.

A convenient network of fueling stations was first promised a decade ago — coined as California’s “hydrogen highway” — but foundered as engineers and economists struggled with cost-efficient solutions to producing and delivering hydrogen to vehicles.

The new strategy aims to contain costs by building small clusters of hydrogen stations to provide day-to-day convenience, with a few connector and destination fueling points to accommodate longer trips. State officials say as few as 100 strategically located stations, enough to support 18,000 vehicles, might be the tipping point for a self-sustaining refueling network that can compete with gasoline.

It is still unclear whether even a well-timed rollout of fuel stations and vehicles can entice Californians.

Hyundai has begun leasing a family-sized SUV for $499 a month, including a $3,000 down payment. The deal includes unlimited hydrogen refueling. Next year, Toyota plans to start selling a Prius-like hydrogen sedan, but has not disclosed a price in the U.S. In Japan, the price was announced at just under $70,000.

Battery powered vehicles range from $29,000 for the Nissan Leaf to $71,000 or more for a luxury Tesla Model S.

In California, fuel cell cars come with a state-funded rebate of $5,000, and up to $15,000 in certain low-income communities, according to Brett Williams, senior program manager for electric vehicles at the Center for Sustainable Energy, which administers state clean-vehicle rebate programs for California and Massachusetts. Fewer than 100 rebates have been claimed so far.

One additional perk: Fuel cell cars can ride in the express carpool lane with the driver traveling alone.

“The cars are really quite good at this point but the infrastructure has remained the Achilles’ heel,” he said.

Fuel cells vehicles convert hydrogen to electricity using a chemical reaction that leaves behind only a trickle of water.

Unlike plug-ins, hydrogen-electric cars can drive for some 300 miles straight and refuel in a matter of minutes. Fuel cells can propel bigger family cars and trucks, the kind many Americans still are not willing to give up.

“For people who want a larger car, who want more of a similar experience in terms of range and refueling to the gasoline cars that they are driving today, battery-electric cars aren’t there,” said Catherine Dunwoody, chief of the fuel cell program at the California Air Resources Board. “Some people say they will be there. I think it would be risky to bet on that, given the advancement we need” on reducing pollution and greenhouse emission linked to climate change.

San Diego has been identified as an important potential sales market for fuel cell vehicles.

“Initially it’s a destination station, but it very quickly becomes its own cluster” for refueling stations, Dunwoody said.

Most hydrogen, used for hydrogenating food products and refining gasoline, currently comes from a process that combines steam and natural gas and does emit greenhouse gases.

Hydrogen supplied to California drivers must be certified as one-third renewable — substituting nonrenewable natural gas with methane captured from landfills and sewage treatment facilities. Two of the new California fueling points will provide 100 percent renewable hydrogen.

Emissions-free hydrogen production — using renewable such as solar energy to separate hydrogen from water through electrolysis — remains prohibitively expensive, a problem aggravated by cheap, plentiful U.S. natural gas. The equation may not change for decades.

Based on that panorama and advances in battery-electric cars, a vocal group of experts view investments in hydrogen infrastructure as unwise.

The loudest critical voice may be Tesla Motors founder Elon Musk, as he steers public support behind Tesla’s battery-electric vehicles.

Tam Hunt, a renewable energy policy consultant and blogger at Community Renewable Solutions in Santa Barbara, is among those questioning whether public policies supporting fuel cell vehicles really helps with the transition away from fossil fuels.

As long as hydrogen is tied to natural gas, benefits have to be weighed against the environmental toll of fracking techniques for extracting natural gas, Hunt argues. So-called green hydrogen still faces the problem of wasted energy from converting renewable electricity to hydrogen and back again in a car, he explained in a recent blog post.

“As hydrogen is increasingly produced from renewable electricity, it makes far more sense to use that electricity directly in battery-electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles due to the large conversion losses from making hydrogen with electricity.”

California is not alone in its embrace of fuel cell vehicles. Japan, South Korea,

German and England also are building their first hydrogen fueling clusters, with a combination of public and private investment.

The first direct retail sales of hydrogen in California are likely just months away, as the state Division of Measurement Standards completes enforceable guidelines for dispensing hydrogen by the kilogram.

The gradual opening of the hydrogen highway has enthusiasts delighted by new possibilities.

General Motors officials envision a fuel cell car that may some day be parked and plugged into a house to function as a backup 25 kilowatt generator. Eventually, surplus solar and wind power from the electric grid might be diverted to producing hydrogen — effectively storing green energy in a bottle.

Hydrogen currently used to refine gasoline could very well go directly into the vehicle fuel tanks of the future, said Scott Samuelsen, an engineering professor at the National Fuel Cell Research Center at University of California Irvine.

Like California policy makers, he too says the monopoly of gasoline and diesel cars will not be broken by battery-electric vehicles alone.

“It’s not expected that the battery will displace all of the gasoline vehicles and that’s where the hydrogen vehicle fits in,” he said. “As time goes on, I think the public will realize that both of these technologies are needed and desired — the electric vehicle for the shorter trips and the hydrogen for the longer trips.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.