Here comes El Niño

A spike in Pacific Ocean sea temperatures and the rapid movement of warm water eastwards have increased fears that this year’s El Niño could be one of the strongest yet.

El Niño - a warming of sea-surface temperatures in the Pacific - affects wind patterns and can trigger both floods and drought in different parts of the globe.

Although previous research has suggested extreme El Niño events could occur later this year, experts claim this recent rise hints they are likely to be more significant than first thought.

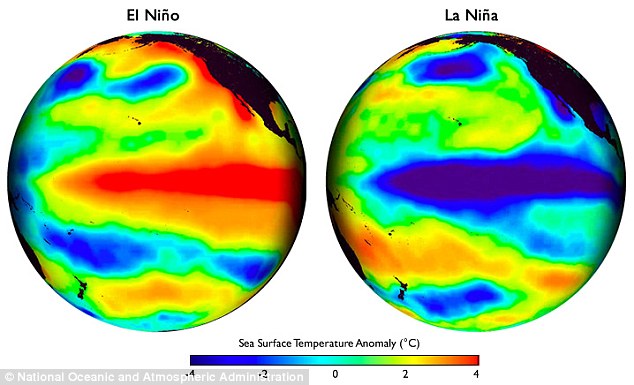

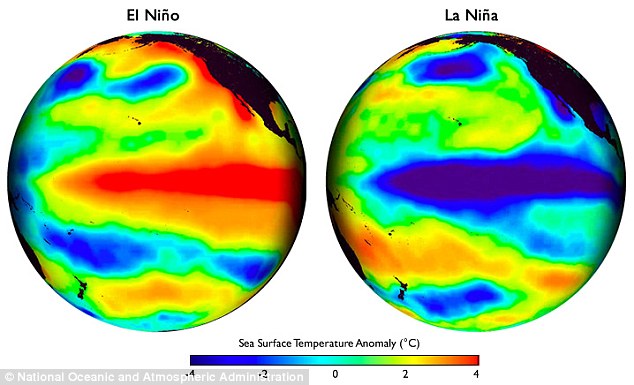

A spike in Pacific Ocean sea temperatures and the rapid movement of warm water eastwards have increased fears this year’s El Niño could be one of the strongest yet. El Niño, pictured left, is a warming of sea temperatures that can trigger floods and droughts. La Niña, pictured right, is when sea temperatures drop

Dr Wenju Cai, a climate expert at Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, said the rises in Pacific Ocean temperature were above those seen in previous El Niño years.

‘I think this event has lots of characteristics with a strong El Niño,’ said Cai.

‘A strong El Nino appears early and we have seen this event over the last couple of months, which is unusual; the wind that has caused the warming is quite large and there is what we call the pre-conditioned effects, where you must have a lot of heat already in the system to have a big El Niño event.’

He based his conclusions on studying data released by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

A majority of weather forecasting models indicate that the phenomenon may develop around the middle of the year, but it was too early to assess its likely strength, the U.N. World Meteorological Organization said on 15 April.

Meteorologists added the prospect of an El Niño will likely be firmed up ‘in the next month or two’, although forecasting its strength will be hard to do.

The chance of an it developing in 2014 exceeded 70 per cent according to Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology.

Its weather bureau is expected to issue its next El Niño outlook report on Tuesday, while Japan’s meteorological agency is expected to updated its forecast in the next couple of weeks.

The worst El Niño on record in 1997 and 1998 was blamed for massive flooding along China’s Yangtze river, responsible for killing more than 1,500 people.

The impact of extreme El Niño events is felt by every continent, and the event in 1997 cost between $35billion to $45billion in damage globally.

A strong El Niño also increases fears that production of many key agricultural commodities in Asia and Australia will suffer.

In January, a team of international scientists said extreme weather events fuelled by unusually strong El Niños are expected to double over the next century.

Climate scientists warned countries could be struck by devastating droughts, wild fires and dramatic foods approximately every ten years.

The team, made up of experts from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science (CoECSS), the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and CSIRO, also spotted a link between global warming and extreme El Niño events.

‘We currently experience an unusually strong El Niño event every 20 years. Our research shows this will double to one event every 10 years,’ said Agus Santoso of CoECSS, who co-authored the study.

‘El Niño events are a multi-dimensional problem and only now are we starting to understand better how they respond to global warming,’ he added.

Extreme El Niño events develop differently from standard El Niños, which first appear in the western Pacific.

The extreme events occur when sea surface temperatures exceeding 28°C develop in the normally cold and dry eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean.

This different location for the origin of the temperature increase causes massive changes in global rainfall patterns, which result in floods and torrential rain in some places and devastating droughts and wild fires in others.

The impacts of extreme El Niño events that extended to every continent across the globe in 1997, for example, killed around 23,000 people.

Dr Cai continued: ‘During an extreme El Niño event countries in the western Pacific, such as Australia and Indonesia, experienced devastating droughts and wild fires, while catastrophic floods occurred in the eastern equatorial region of Ecuador and northern Peru.’

In Australia, the drought and dry conditions caused by the 1982 and 1983 extreme El Niño led to the Ash Wednesday Bushfire in southeast Australia, which resulted in 75 deaths.

El Niño - a warming of sea-surface temperatures in the Pacific - affects wind patterns and can trigger both floods and drought in different parts of the globe.

Although previous research has suggested extreme El Niño events could occur later this year, experts claim this recent rise hints they are likely to be more significant than first thought.

A spike in Pacific Ocean sea temperatures and the rapid movement of warm water eastwards have increased fears this year’s El Niño could be one of the strongest yet. El Niño, pictured left, is a warming of sea temperatures that can trigger floods and droughts. La Niña, pictured right, is when sea temperatures drop

Dr Wenju Cai, a climate expert at Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, said the rises in Pacific Ocean temperature were above those seen in previous El Niño years.

‘I think this event has lots of characteristics with a strong El Niño,’ said Cai.

‘A strong El Nino appears early and we have seen this event over the last couple of months, which is unusual; the wind that has caused the warming is quite large and there is what we call the pre-conditioned effects, where you must have a lot of heat already in the system to have a big El Niño event.’

He based his conclusions on studying data released by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

A majority of weather forecasting models indicate that the phenomenon may develop around the middle of the year, but it was too early to assess its likely strength, the U.N. World Meteorological Organization said on 15 April.

Meteorologists added the prospect of an El Niño will likely be firmed up ‘in the next month or two’, although forecasting its strength will be hard to do.

The chance of an it developing in 2014 exceeded 70 per cent according to Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology.

Its weather bureau is expected to issue its next El Niño outlook report on Tuesday, while Japan’s meteorological agency is expected to updated its forecast in the next couple of weeks.

The worst El Niño on record in 1997 and 1998 was blamed for massive flooding along China’s Yangtze river, responsible for killing more than 1,500 people.

The impact of extreme El Niño events is felt by every continent, and the event in 1997 cost between $35billion to $45billion in damage globally.

A strong El Niño also increases fears that production of many key agricultural commodities in Asia and Australia will suffer.

In January, a team of international scientists said extreme weather events fuelled by unusually strong El Niños are expected to double over the next century.

Climate scientists warned countries could be struck by devastating droughts, wild fires and dramatic foods approximately every ten years.

The team, made up of experts from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science (CoECSS), the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and CSIRO, also spotted a link between global warming and extreme El Niño events.

‘We currently experience an unusually strong El Niño event every 20 years. Our research shows this will double to one event every 10 years,’ said Agus Santoso of CoECSS, who co-authored the study.

‘El Niño events are a multi-dimensional problem and only now are we starting to understand better how they respond to global warming,’ he added.

Extreme El Niño events develop differently from standard El Niños, which first appear in the western Pacific.

The extreme events occur when sea surface temperatures exceeding 28°C develop in the normally cold and dry eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean.

This different location for the origin of the temperature increase causes massive changes in global rainfall patterns, which result in floods and torrential rain in some places and devastating droughts and wild fires in others.

The impacts of extreme El Niño events that extended to every continent across the globe in 1997, for example, killed around 23,000 people.

Dr Cai continued: ‘During an extreme El Niño event countries in the western Pacific, such as Australia and Indonesia, experienced devastating droughts and wild fires, while catastrophic floods occurred in the eastern equatorial region of Ecuador and northern Peru.’

In Australia, the drought and dry conditions caused by the 1982 and 1983 extreme El Niño led to the Ash Wednesday Bushfire in southeast Australia, which resulted in 75 deaths.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.