Group wants Lac-Mégantic contamination records made public

Quebec is refusing to make public all the information it has about the contamination of the Chaudière riverbed caused by the Lac-Mégantic train derailment seven months ago.

An environmental group is trying to force its hand, asking Quebec’s access-to-information commission to compel the government to make the data public because it is particularly concerned about the section of the river closest to the derailment site.

The Société pour vaincre la pollution (SVP) had asked Quebec’s environment minister for all information it has about contamination of the sediments at the bottom of the Chaudière River.

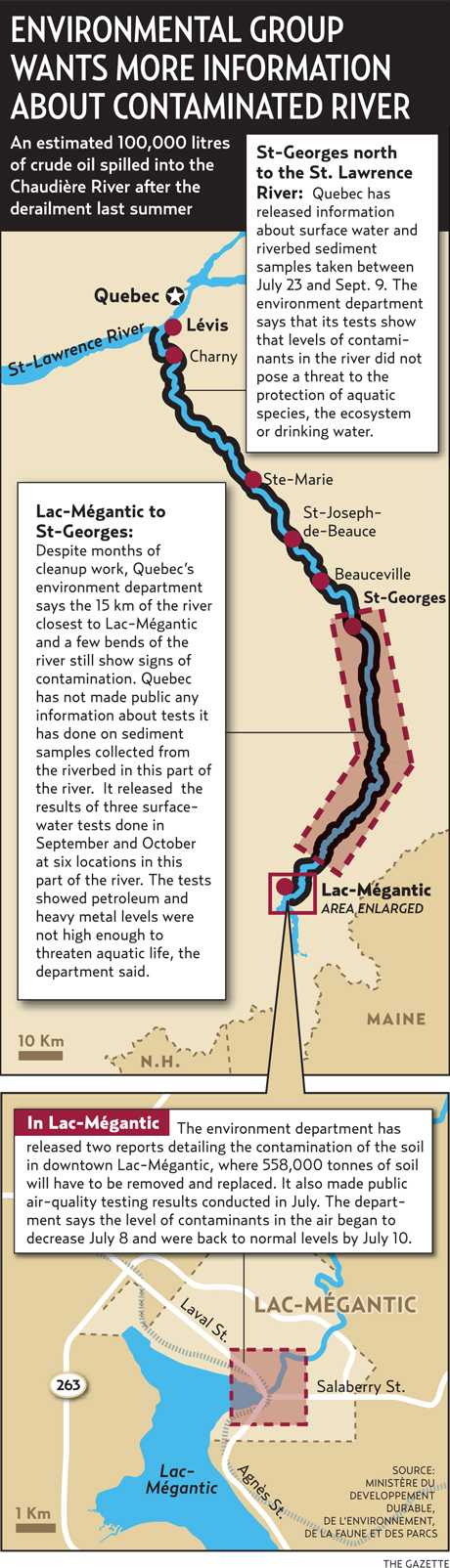

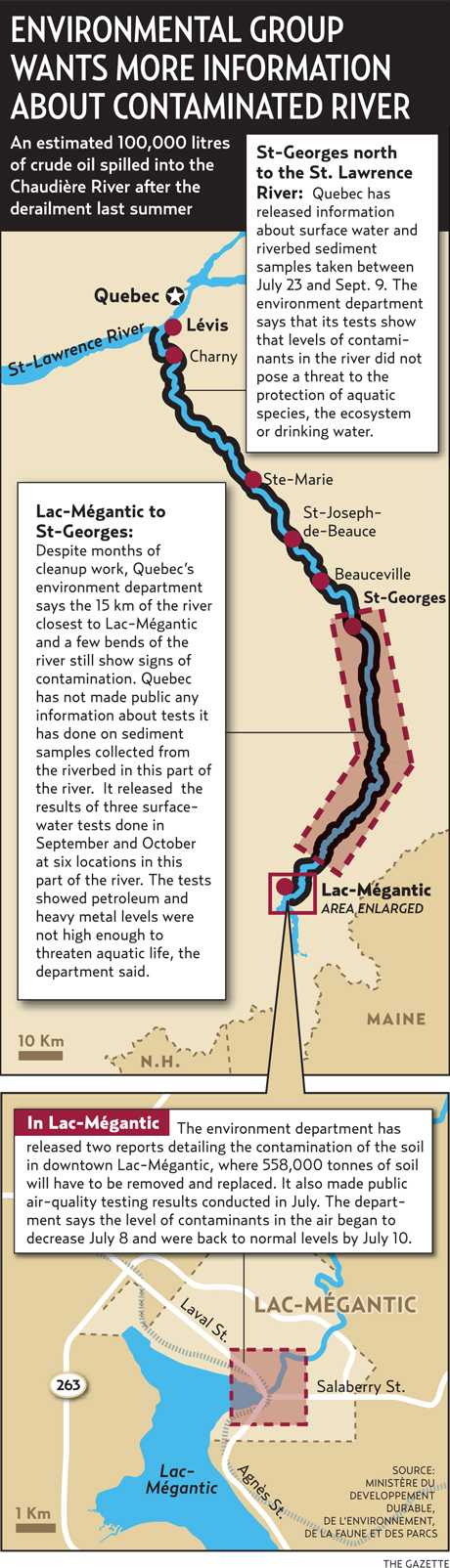

The environment department estimates 100,000 litres of the crude oil that spilled in the July 6 derailment and fire made its way into the river, which winds its way 185 kilometres from Lac-Mégantic to the St. Lawrence River near Quebec City.

In the seven months since the accident, Quebec has published surface water and riverbed sediment analysis from the part of the Chaudière River between the town of St-Georges — 80 km from the crash site — and the St. Lawrence River.

The only test results it has published so far for the other half of the river — the part closest to the accident site — was for three weekly surface-water tests conducted in September and October.

In both cases, the government said the results of those tests showed the contamination levels in the river were not high enough to cause harm to aquatic life, the ecosystem or drinking water.

According to documents filed with the Tribunal administratif du Québec, which is hearing an appeal from six companies that Quebec has ordered to pay for the cleanup and decontamination from the derailment, sediment samples were collected at three locations in the river between Lac-Mégantic and St-Georges between July 18 and 30.

In late July, after riverside residents reported seeing oil coming up from the bottom of the river, an internal environment department document filed with the TAQ says sediment samples were also collected for analysis.

In November, SVP and Greenpeace revealed their own testing of sediment samples collected in October showing oil and other contaminants in the riverbed. At the time, Environment Minister Yves-François Blanchet said the environmental groups’ findings confirmed his own department’s finding for the Chaudière riverbed, and that more than 600 samples of sediment collected from the riverbed were being analyzed.

The results of the government’s testing are to be given to an expert committee that is drawing up a management plan for the river, environment department officials told Lac-Mégantic residents two weeks ago. Blanchet has said the test results and the report are to be made public in the spring.

SVP filed an access-to-information request after Blanchet’s announcement in November, asking for all information the environment department has about contaminants from the derailment in the riverbed sediment.

Just before Christmas, the environment department told SVP said it would not provide the results of sediment sampling it did between September and November 2013 because that information is to be published within the next six months.

The department also said it couldn’t provide SVP with other documents, citing a clause in Quebec’s access-to-information law that prevents the distribution of information related to a crime.

There are several ongoing investigations into the Lac-Mégantic derailment, including a criminal investigation by the Sûreté du Québec, and investigations by Transport Canada and Environment Canada for possible contravention of federal transportation regulations and fisheries and migratory birds’ laws.

SVP’s Daniel Green said he thinks the government has been trying to minimize the contamination caused by the derailment, and argues the contamination data should be made public because the state of the river is a public-safety issue.

SVP has asked the access commission to consider its request to overturn the environment department’s decision in an urgent manner because of the possible effects that ice-break up and spring flooding could have on contaminants in the river. Green says oily water could also spill over the riverbanks and contaminate agricultural land along the river.

The environment department has said it will monitor the river, but said there is a very low risk of oily water affecting land along the river during the spring thaw.

“There’s a fear of worrying people,” Green said. “But my experience dealing with contamination and citizens is that citizens are mature, citizens are reasonable and they would rather know than not know.”

Greenpeace has also asked the environment department to make public the information it has about the contamination of the Chaudière, in particular the section of the river closest to Lac-Mégantic, said spokesperson Patrick Bonin.

With more oil coming into the province by rail, on ships, and potentially via two different pipelines, Quebec has to be prepared for more spills, he said.

“The amount in one tanker car — 100,000 litres — entered the Chaudière, according to the government’s calculations,” Bonin said. “The next spill could be much larger, and I doubt that Quebec is prepared to intervene quickly to recover large amounts of oil and to quickly decontaminate.

Green said making public all the information the government has about the extent of the contamination of the river is necessary to evaluate whether Quebec can respond to a spill.

“There’s a very significant likelihood of this happening again. Maybe not with the death and destruction, but oil on the ground and in the water,” Green said. “It is by dissecting a spill that we find out exactly what we need to deal with the next one.”

A spokesperson for Quebec’s environment department said it would respect the access commission’s decision.

An environmental group is trying to force its hand, asking Quebec’s access-to-information commission to compel the government to make the data public because it is particularly concerned about the section of the river closest to the derailment site.

The Société pour vaincre la pollution (SVP) had asked Quebec’s environment minister for all information it has about contamination of the sediments at the bottom of the Chaudière River.

The environment department estimates 100,000 litres of the crude oil that spilled in the July 6 derailment and fire made its way into the river, which winds its way 185 kilometres from Lac-Mégantic to the St. Lawrence River near Quebec City.

In the seven months since the accident, Quebec has published surface water and riverbed sediment analysis from the part of the Chaudière River between the town of St-Georges — 80 km from the crash site — and the St. Lawrence River.

The only test results it has published so far for the other half of the river — the part closest to the accident site — was for three weekly surface-water tests conducted in September and October.

In both cases, the government said the results of those tests showed the contamination levels in the river were not high enough to cause harm to aquatic life, the ecosystem or drinking water.

According to documents filed with the Tribunal administratif du Québec, which is hearing an appeal from six companies that Quebec has ordered to pay for the cleanup and decontamination from the derailment, sediment samples were collected at three locations in the river between Lac-Mégantic and St-Georges between July 18 and 30.

In late July, after riverside residents reported seeing oil coming up from the bottom of the river, an internal environment department document filed with the TAQ says sediment samples were also collected for analysis.

In November, SVP and Greenpeace revealed their own testing of sediment samples collected in October showing oil and other contaminants in the riverbed. At the time, Environment Minister Yves-François Blanchet said the environmental groups’ findings confirmed his own department’s finding for the Chaudière riverbed, and that more than 600 samples of sediment collected from the riverbed were being analyzed.

The results of the government’s testing are to be given to an expert committee that is drawing up a management plan for the river, environment department officials told Lac-Mégantic residents two weeks ago. Blanchet has said the test results and the report are to be made public in the spring.

SVP filed an access-to-information request after Blanchet’s announcement in November, asking for all information the environment department has about contaminants from the derailment in the riverbed sediment.

Just before Christmas, the environment department told SVP said it would not provide the results of sediment sampling it did between September and November 2013 because that information is to be published within the next six months.

The department also said it couldn’t provide SVP with other documents, citing a clause in Quebec’s access-to-information law that prevents the distribution of information related to a crime.

There are several ongoing investigations into the Lac-Mégantic derailment, including a criminal investigation by the Sûreté du Québec, and investigations by Transport Canada and Environment Canada for possible contravention of federal transportation regulations and fisheries and migratory birds’ laws.

SVP’s Daniel Green said he thinks the government has been trying to minimize the contamination caused by the derailment, and argues the contamination data should be made public because the state of the river is a public-safety issue.

SVP has asked the access commission to consider its request to overturn the environment department’s decision in an urgent manner because of the possible effects that ice-break up and spring flooding could have on contaminants in the river. Green says oily water could also spill over the riverbanks and contaminate agricultural land along the river.

The environment department has said it will monitor the river, but said there is a very low risk of oily water affecting land along the river during the spring thaw.

“There’s a fear of worrying people,” Green said. “But my experience dealing with contamination and citizens is that citizens are mature, citizens are reasonable and they would rather know than not know.”

Greenpeace has also asked the environment department to make public the information it has about the contamination of the Chaudière, in particular the section of the river closest to Lac-Mégantic, said spokesperson Patrick Bonin.

With more oil coming into the province by rail, on ships, and potentially via two different pipelines, Quebec has to be prepared for more spills, he said.

“The amount in one tanker car — 100,000 litres — entered the Chaudière, according to the government’s calculations,” Bonin said. “The next spill could be much larger, and I doubt that Quebec is prepared to intervene quickly to recover large amounts of oil and to quickly decontaminate.

Green said making public all the information the government has about the extent of the contamination of the river is necessary to evaluate whether Quebec can respond to a spill.

“There’s a very significant likelihood of this happening again. Maybe not with the death and destruction, but oil on the ground and in the water,” Green said. “It is by dissecting a spill that we find out exactly what we need to deal with the next one.”

A spokesperson for Quebec’s environment department said it would respect the access commission’s decision.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.