Global warming could fuel European hurricanes

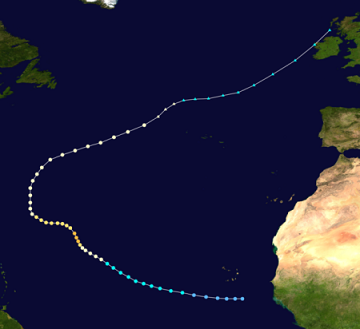

European climate scientists say global warming will drive a northeastward expansion of the tropical Atlantic hurricane breeding ground, with four times as many storms of tropical origins affecting parts of Western Europe in coming decades.

European climate scientists say global warming will drive a northeastward expansion of the tropical Atlantic hurricane breeding ground, with four times as many storms of tropical origins affecting parts of Western Europe in coming decades.In the Bay of Biscay, the number of storms with tropical-storm-force winds could increase from 2 to 13 by the end of the century, said researcher Reindert Haarsma.

The initial results suggest that the impacts may not be as great in the low-lying Netherlands as in some other areas because the strong winds associated with the events will generally be from the southwest, Haarsma said.

With hurricanes forming farther north and warmer sea surface temperatures in the region, tropical storms are more likely to reach the mid-latitudes, where they will merge with the prevailing westerlies. Even if they lose hurricane status, they are likely to remain stronger, and sometimes re-intensify before landfall, potentially with serious impacts in parts of Europe.

“Our model simulations clearly show that future tropical cyclones are more prone to hit Western Europe and do so earlier in the season,” said the researchers with the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute.

The study focused on four areas: Norway, the North Sea, the western UK and the Gulf of Biscay. The results suggest there will be a an increase in the frequency of severe winds in the North Sea and the Gulf of Biscay during autumn, but the signal is less clear for the other two areas.

Now, most storms that bring hurricane-force winds to Western Europe begin as extratropical storms. But that will change in the future, when most will originate in the tropics as hurricanes or tropical storms, potentially delivering more moisture.

Haarsma said some follow-up research is under way to quantify the changes in moisture and rainfall associated with the changes in tropical storm formation and trajectories. Increased rainfall from the storms also has the potential for major impacts in coastal mountains and watersheds, he said.

“The result seems plausible,” said Kevin Trenberth, head of the Climate Analysis Section at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. Global warming will expand the zones where the ocean is warm enough to fuel hurricanes, Trenberth said via email.

“The result they get is robust in that regard … The storms are extratropical storms with strong winds, that may have had tropical origins when they were hurricanes … They are not hurricanes in Europe,” he said. “The study focuses on winds, but the real story, I bet, is precipitation,” he said, using Hurricane Irene and Superstorm Sandy as analogies.

In 2011, Irene moved out of the Caribbean, up the East Coast and pounded New England with flooding rains after becoming an extratropical cyclone near the Vermont-New Hampshire border. Sandy also became extratropical shortly after making landfall in New Jersey but raked the Northeast with hurricane-like impacts.

“The resulting flooding episodes will likely dwarf the wind damage, although in some places like the Netherlands, both together could be disastrous,” Trenberth said.

“Sandy was a beautiful example: Mixed character, probably no eye but a lot bigger in size and strong winds for miles, and heavy rains. These are now quite common in the Pacific Northwest with Typhoons that hit Japan and China, and what this paper says is that they could become more common in the Atlantic and affect Europe. Seems likely

to me,” he concluded.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.