Futuristic fleet of 'cloudseeders'

(by Professor John Latham) - Some experts are proposing radical ideas to save us from disastrous climate change. But would they work? Professors John Latham and Stephen Salter have designed a fleet of yachts that would pump fine particles of sea-water into clouds, thickening them to reflect more of the Sun’s rays. Here, Professor Latham talks about the proposal.

(by Professor John Latham) - Some experts are proposing radical ideas to save us from disastrous climate change. But would they work? Professors John Latham and Stephen Salter have designed a fleet of yachts that would pump fine particles of sea-water into clouds, thickening them to reflect more of the Sun’s rays. Here, Professor Latham talks about the proposal.“It was in 1946 that scientists first began trying to manipulate clouds.

They found that by firing tiny particles of silver iodide into rain-bearing clouds, they could induce rainfall.

Our idea of a fleet of “cloudseeders”, however, was largely born from a remark made by my son Mike, decades ago.

We were on a mountainside in North Wales, looking west towards Ireland.

He asked why clouds were shiny at the top but dark at the bottom.

I explained how they were mirrors for incoming sunlight.

He pondered for a while, then grinned: “Soggy mirrors, Dad,” he said.

The idea my colleagues and I are pursuing is to increase the amount of sunlight reflected back into space from the tops of thin, low-level clouds (marine stratocumuli, which cover about a quarter of the world’s oceanic surface), thereby producing a cooling effect.

Calculations show that if we can increase the reflectivity by about 3%, the cooling will balance the global warming caused by increased CO2 in the atmosphere (resulting from the burning of fossil fuels).

Cloud-seeding yachts

In order to deploy our scheme and produce adequate cooling, we would need to spray sea-water droplets continuously over a significant fraction of the world’s oceanic surface, at a total rate of around 50 cubic metres per second.

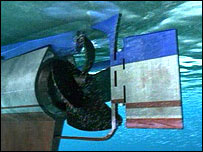

Professor Stephen Salter has developed plans for a novel form of spray-droplet production (involving high-velocity propulsion of sea-water droplets), and has designed a wind-powered unmanned vessel which can be remotely guided to regions where cloud seeding is most favourable.

Instead of sails, these vessels use a much more efficient technique to power the yacht - Flettner rotors.

These spinning vertical cylinders mounted on the deck are named after their inventor, Anton Flettner. They also house the spraying system which sprays sea-water droplets from the top of the rotors.

The power required for spraying, communications and so on comes from electricity generated by turbines dragged along by the vessels.

We envisage that about 1,000 such vessels would be required to make the scheme effective.

Under control

The ideal solution to the global warming problem is that the burning of fossil fuels be drastically reduced.

But our scheme offers the possibility that we could buy time within which catastrophic warming could be staved off while carbon dioxide levels are being reduced to an acceptable degree.

One advantage of our plan is that it is ecologically benign; the only raw material required being sea-water.

The amount of cooling could be controlled, via satellite measurements and a computer model, and if an emergency arose, the system could be switched off, with conditions returning to normal within a few days.

In addition to global temperature stabilisation, we also envisage that the technique could be used to remedy more regional problems, such as the dying of the coral reefs as a result of ocean warming.

Long road ahead

But while it is all very well spraying the clouds, what effect will this have on the world’s fragile eco-system, and do we have the right to interfere with the planet in this way?

Before we could justify deploying such a scheme on a global scale we would need to do several things.

We would have to complete the development of the required technology, and conduct a limited-area field experiment in which the reflectivity of seeded clouds is compared with that of adjacent unseeded ones.

We would also have to perform detailed analysis to establish whether there might be serious or harmful meteorological or climatological ramifications (such as reducing rainfall in regions where water is scarce) and, if so, to find a solution for them.

But bearing all this in mind, we have been encouraged by the consistent response we have received to our scheme - for example at a recent Nasa meeting - and it seems likely to be a strong contender in the fight to improve the current global warming problem worldwide.

When the planet is in such a dire situation, I am convinced it is simply irresponsible not to at least examine our options.

Professor John Latham is an atmospheric physicist at the University of Manchester & NCAR, Colorado, US. Professor Stephen Salter is an engineer at the University of Edinburgh.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.