From Heat Wave to Snowstorms, March Goes to Extremes

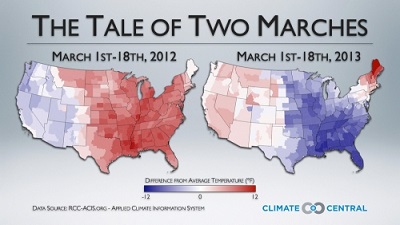

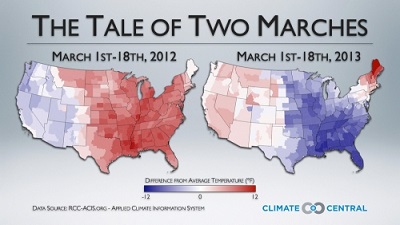

What a difference a year makes.

Last March, the U.S. was basking in a heat wave that drove temperatures into the 70s all the way to the Canadian border, as winter snows rapidly retreated and flowers bloomed. Unaware of the devastating drought to follow, the warmth prompted farmers all across the nation to plant their crops several weeks early, and a record corn harvest was predicted.

Fast forward to March 2013 and millions of Americans are shivering as an unrelenting string of winter storms have brought heavy snow from the Midwest to the Northeast, and colder-than-average temperatures to much of the East since February.

The past two days have provided the perfect example of that weather. On Tuesday, heavy snow fell across much of New England, bringing a foot or more of snow. That after Monday’s nasty wintry mix of snow, sleet, and freezing rain pelted New Yorkers.

To put that weather in context, consider that by March 19, 2012, more than 2,200 warm-temperature records had been set or tied across the U.S. That is about 1,000 more than had been set or tied so far this March.

Perhaps no other location best illustrates the whiplash between March 2012 and March 2013 than International Falls, Minn., known as the “Icebox” of the nation. On March 18, 2012, International Falls recorded a high temperature of 79ºF, which was a monthly all-time high.

And what was the high temperature in International Falls on Monday? A chilly 28°F, with a low of 14°F. It was even colder on Tuesday, with the forecast high temperature of just 16°F.

A similar reversal is occurring in Chicago, where the first day of spring last year brought a high temperature of 85°F, which was a monthly record. This year? Try 60-degrees cooler, with a forecast high on Wednesday of just 25°F.

The weather pattern that is responsible for this year’s cold weather is unusual, even though it is not yielding extremely cold temperatures across the U.S. In fact, March is running near average for the lower 48 states. Still, after last year’s nonexistent winter and downright summer-like spring, any cold and snow in March may seem like a shock to the system.

The weather map across the Northern Hemisphere features a sprawling and unusually strong area of High pressure over Greenland that is serving as an atmospheric stop sign, slowing weather systems as they move from west to east, and allowing storms to deepen off the eastern seaboard and tap into more cold air than they otherwise might have.

The weather map across the Northern Hemisphere features a sprawling and unusually strong area of High pressure over Greenland that is serving as an atmospheric stop sign, slowing weather systems as they move from west to east, and allowing storms to deepen off the eastern seaboard and tap into more cold air than they otherwise might have.

That is not your typical fair weather area of High pressure, either. Some computer models have been projecting that, sometime during the next couple of days, the Greenland High could come close to setting the mark for the highest atmospheric pressure ever recorded.

The blocking pattern has helped direct cold air into the lower 48 states as well as parts of Europe, while the Arctic has been experiencing dramatically warmer-than-average conditions, particularly along the west coast of Greenland and in northeastern Canada. Blocking patterns are often associated with extreme weather events, from heat waves like the one that occurred last March, to historic cold air outbreaks and blizzards.

A similar blocking pattern was in place at precisely the wrong time in October 2012, as Hurricane Sandy made its way northward from the Caribbean. The convoluted jet stream pulled Sandy westward into New Jersey, with devastating results. Some researchers have hypothesized that this blocking pattern was related to Arctic climate change.

One way to view the blocking pattern is through the lens of the Arctic Oscillation, or AO, which is a large-scale variation in surface air pressure between the Arctic and the mid-latitudes. When the AO is in a negative phase, the average surface air pressure is above average in the Arctic and below average in the mid-latitudes. This sets up opposing temperature patterns, with warmer-than-average conditions in parts of the Arctic, and cooler-than-average conditions in parts of North America and Europe. Right now the AO index is at its lowest reading of anytime during the 2012-2013 winter.

Arctic climate change fingerprints?

Recent research suggests that rapid Arctic climate change, namely the loss of sea ice cover, may be contributing to blocking patterns like we’re seeing right now. That rapid decline in Arctic sea ice since the beginning of the satellite record in 1979 may be altering weather patterns both in the Far North and across the U.S.. Some studies have shown that sea ice loss favors atmospheric blocking patterns such as the pattern currently in place, while others have not shown statistically significant changes in blocking patterns across the Northern Hemisphere, at least not yet. Arctic sea ice extent declined to a record low during the 2012 melt season.

A study published in 2012 showed that by changing the temperature balance between the Arctic and mid-latitudes, rapid Arctic warming is altering the course of the jet stream, which steers weather systems from west to east around the northern hemisphere. The Arctic has been warming about twice as fast as the rest of the Northern Hemisphere, due to a combination of human emissions of greenhouse gases and unique feedbacks built into the Arctic climate system. The jet stream, the study said, is becoming “wavier,” with steeper troughs and higher ridges.

A new study published in the journal Environmental Research Letters shows that reduced sea ice cover can favor colder and stormier winters in the northern midlatitudes.

As sea ice melts, it exposes darker ocean water, which absorbs more of the sun’s heat, causing the water temperatures to increase. During the fall, the heat that was added to the oceans gets released into the atmosphere as sea ice reforms, and this added heat is bound to change weather patterns somehow (this is a process known as “Arctic Amplification”). The “how” part is what’s open to debate.

Researchers examining the possible links between Arctic warming and the weather in the U.S., Europe, and other areas must contend with the large amount of natural variability that affects winter weather patterns, and the very short observational record of how the atmosphere responded to extreme losses of sea ice. In addition, climate models actually show a reduction in blocking patterns in the Northern Hemisphere, rather than the increase that one would expect given a warming planet with less Arctic sea ice. However, the models may not be capturing blocking well at the present time, let alone the future.

Last March, the U.S. was basking in a heat wave that drove temperatures into the 70s all the way to the Canadian border, as winter snows rapidly retreated and flowers bloomed. Unaware of the devastating drought to follow, the warmth prompted farmers all across the nation to plant their crops several weeks early, and a record corn harvest was predicted.

Fast forward to March 2013 and millions of Americans are shivering as an unrelenting string of winter storms have brought heavy snow from the Midwest to the Northeast, and colder-than-average temperatures to much of the East since February.

The past two days have provided the perfect example of that weather. On Tuesday, heavy snow fell across much of New England, bringing a foot or more of snow. That after Monday’s nasty wintry mix of snow, sleet, and freezing rain pelted New Yorkers.

To put that weather in context, consider that by March 19, 2012, more than 2,200 warm-temperature records had been set or tied across the U.S. That is about 1,000 more than had been set or tied so far this March.

Perhaps no other location best illustrates the whiplash between March 2012 and March 2013 than International Falls, Minn., known as the “Icebox” of the nation. On March 18, 2012, International Falls recorded a high temperature of 79ºF, which was a monthly all-time high.

And what was the high temperature in International Falls on Monday? A chilly 28°F, with a low of 14°F. It was even colder on Tuesday, with the forecast high temperature of just 16°F.

A similar reversal is occurring in Chicago, where the first day of spring last year brought a high temperature of 85°F, which was a monthly record. This year? Try 60-degrees cooler, with a forecast high on Wednesday of just 25°F.

The weather pattern that is responsible for this year’s cold weather is unusual, even though it is not yielding extremely cold temperatures across the U.S. In fact, March is running near average for the lower 48 states. Still, after last year’s nonexistent winter and downright summer-like spring, any cold and snow in March may seem like a shock to the system.

The weather map across the Northern Hemisphere features a sprawling and unusually strong area of High pressure over Greenland that is serving as an atmospheric stop sign, slowing weather systems as they move from west to east, and allowing storms to deepen off the eastern seaboard and tap into more cold air than they otherwise might have.

The weather map across the Northern Hemisphere features a sprawling and unusually strong area of High pressure over Greenland that is serving as an atmospheric stop sign, slowing weather systems as they move from west to east, and allowing storms to deepen off the eastern seaboard and tap into more cold air than they otherwise might have.That is not your typical fair weather area of High pressure, either. Some computer models have been projecting that, sometime during the next couple of days, the Greenland High could come close to setting the mark for the highest atmospheric pressure ever recorded.

The blocking pattern has helped direct cold air into the lower 48 states as well as parts of Europe, while the Arctic has been experiencing dramatically warmer-than-average conditions, particularly along the west coast of Greenland and in northeastern Canada. Blocking patterns are often associated with extreme weather events, from heat waves like the one that occurred last March, to historic cold air outbreaks and blizzards.

A similar blocking pattern was in place at precisely the wrong time in October 2012, as Hurricane Sandy made its way northward from the Caribbean. The convoluted jet stream pulled Sandy westward into New Jersey, with devastating results. Some researchers have hypothesized that this blocking pattern was related to Arctic climate change.

One way to view the blocking pattern is through the lens of the Arctic Oscillation, or AO, which is a large-scale variation in surface air pressure between the Arctic and the mid-latitudes. When the AO is in a negative phase, the average surface air pressure is above average in the Arctic and below average in the mid-latitudes. This sets up opposing temperature patterns, with warmer-than-average conditions in parts of the Arctic, and cooler-than-average conditions in parts of North America and Europe. Right now the AO index is at its lowest reading of anytime during the 2012-2013 winter.

Arctic climate change fingerprints?

Recent research suggests that rapid Arctic climate change, namely the loss of sea ice cover, may be contributing to blocking patterns like we’re seeing right now. That rapid decline in Arctic sea ice since the beginning of the satellite record in 1979 may be altering weather patterns both in the Far North and across the U.S.. Some studies have shown that sea ice loss favors atmospheric blocking patterns such as the pattern currently in place, while others have not shown statistically significant changes in blocking patterns across the Northern Hemisphere, at least not yet. Arctic sea ice extent declined to a record low during the 2012 melt season.

A study published in 2012 showed that by changing the temperature balance between the Arctic and mid-latitudes, rapid Arctic warming is altering the course of the jet stream, which steers weather systems from west to east around the northern hemisphere. The Arctic has been warming about twice as fast as the rest of the Northern Hemisphere, due to a combination of human emissions of greenhouse gases and unique feedbacks built into the Arctic climate system. The jet stream, the study said, is becoming “wavier,” with steeper troughs and higher ridges.

A new study published in the journal Environmental Research Letters shows that reduced sea ice cover can favor colder and stormier winters in the northern midlatitudes.

As sea ice melts, it exposes darker ocean water, which absorbs more of the sun’s heat, causing the water temperatures to increase. During the fall, the heat that was added to the oceans gets released into the atmosphere as sea ice reforms, and this added heat is bound to change weather patterns somehow (this is a process known as “Arctic Amplification”). The “how” part is what’s open to debate.

Researchers examining the possible links between Arctic warming and the weather in the U.S., Europe, and other areas must contend with the large amount of natural variability that affects winter weather patterns, and the very short observational record of how the atmosphere responded to extreme losses of sea ice. In addition, climate models actually show a reduction in blocking patterns in the Northern Hemisphere, rather than the increase that one would expect given a warming planet with less Arctic sea ice. However, the models may not be capturing blocking well at the present time, let alone the future.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.