First "Small Modular" Nuclear Reactors Planned for Tennessee

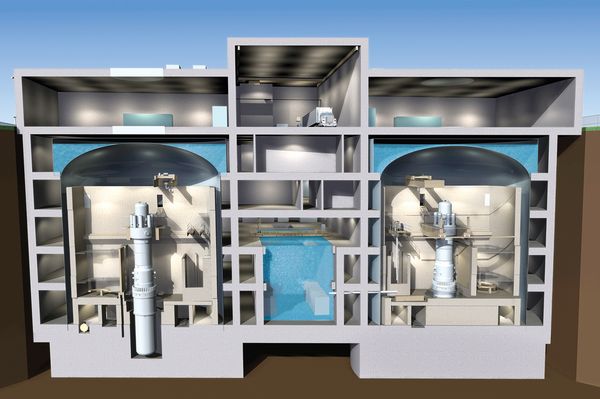

Small modular nuclear reactors, like the one seen illustrated here by the firm Babcock and Wilcox, bring together components that are usually housed separately at full-scale plants. That design feature can boost safety or increase vulnerability, depending on whom you ask.

Near the banks of the Clinch River in eastern Tennessee, a team of engineers will begin a dig this month that they hope will lead to a new energy future.

They’ll be drilling core samples, documenting geologic, hydrologic, and seismic conditions—the initial step in plans to site the world’s first commercial small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs) here.

Once before, there was an effort to hatch a nuclear power breakthrough along the Clinch River, which happens to meander through the U.S. government’s largest science and technology campus, Oak Ridge, on its path from the Appalachian Mountains to the Tennessee River.

In the 1970s, the U.S. government and private industry partners sought to build the nation’s first commercial-scale “fast breeder” reactor here, an effort abandoned amid concerns about costs and safety. Today, nuclear energy’s future still hinges on the same two issues, and advocates argue that SMRs provide the best hope of delivering new nuclear plants that are both affordable and protective of people and the environment. And even amid Washington, D.C.’s budget angst, there was bipartisan support for a new five-year $452 million U.S. government program to spur the technology.

The first project to gain backing in the program is here on the Clinch River at the abandoned fast breeder reactor site, where the Tennessee Valley Authority, the largest public utility in the United States, has partnered with engineering firm Babcock & Wilcox to build two prototype SMRs by 2022.

SMRs are “a very promising direction that we need to pursue,” said U.S. Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz at his confirmation hearing in April. “I would say it’s where the most innovation is going on in nuclear energy.”

The Power of Small

Nuclear power typically is big power, so the drive to downsize marks a significant departure from business as usual. Four of the ten largest electricity stations in the world are nuclear-powered, and the average size of U.S. nuclear reactors is more than 1,000 megawatts (large enough to power about 800,000 U.S. homes). The smallest U.S. reactor in operation, the Fort Calhoun station in Nebraska, is more than 500 MW.

In the first U.S. government-backed SMR effort, Babcock & Wilcox’s nuclear energy subsidiary, B&W mPower, is developing a 180-MW small modular reactor prototype.

Proponents believe a fleet of bite-size reactors might have a better chance of getting built than the typical behemoth. Although existing nuclear reactors (thanks to their cheap fuel) currently provide electricity at lower cost than coal or natural gas plants, building a brand new big nuclear plant is costly.

Tom Flaherty, a senior energy consultant for the global management firm Booz & Company, pointed out that nuclear energy investments often fail to reach fruition. Proposals for 30 new reactors have been advanced by U.S. energy utilities in recent years; more than half of these have been withdrawn to date. A big plant carries another big financial risk; what if there’s not enough demand for all that power?

“In today’s market, the financial risk of unused capacity means nuclear energy is simply not an option unless you are a very large company,” said Flaherty.

Bob Rosner, a nuclear energy expert at the University of Chicago, agreed that the price of a new nuclear plant—which can be around $20 billion—is one that only a handful of energy companies can currently afford.

“Is a company going to bet a third of its market capitalization on a risky project?” Rosner asked. “The answer is no, they aren’t going to do it.” SMRs, however, could be made in factories at the relatively inexpensive cost of $1-2 billion, Rosner said. They could then be shipped via rail to sites around the United States and the world, where they would be ready to “plug and play” upon arrival.

Experts say such reactors also could be removed as a unit, standardizing waste management and recycling of components. SMRs also can be designed with “air cooling,” so that they do not require the large withdrawals of water that today’s current nuclear (and coal) plants need to condense steam.

Christofer Mowry, president and chief executive officer of B&W mPower, said his company’s prototype, currently being tested at a facility in Lynchburg, Virginia, contains all of the components and safety features of a top-of-the-line, full-scale nuclear facility in a module about the size of a Boeing 737 passenger jet.

Mowry views it as an important step in making an essential form of carbon-free energy generation more easily deployable. “There is a convergence or nexus of forces that are really driving the DOE and the world nuclear industry as a whole to focus on this technology,” he said. “There is no silver bullet, but any realistic scenario for power generation over the next 50 years will include nuclear in a big way.”

The other players in the race to develop SMRs span the globe: the U.S. engineering firm Westinghouse (owned by Japan’s Toshiba), South Korea’s Kepco, France’s Areva, and UK-based AMEC. Flaherty said there are five different reactor prototypes under development in Russia. “What makes this so attractive from an international development perspective is that developing countries are hostage to the fuel sources they have,” he said. “This is a technology that you could take in and put anywhere.”

But mPower’s effort, with U.S. government backing, is in the lead. Under the terms of an agreement announced in April, the U.S. Department of Energy will provide mPower with $79 million for the project in the first year, and $226 million or more in federal funding could be available, subject to incremental appropriations from Congress.

Sizing for Safety

Proponents of SMRs say their compact size will help to shore up safety protection. For example, U.S. regulations now require that nuclear power plants are able to maintain core cooling after a power blackout for four to eight hours. The most advanced big reactors, like those being installed at Southern Company’s Vogtle plant now under construction in Georgia, would have the capability to cope with a three-day outage. But SMRs have added safety features that would keep water circulating through a reactor core in the event of power loss, preventing a nuclear meltdown for weeks.

And there are other protections. The two reactors planned at the Clinch River site will be buried underground with a protective slab of concrete on top. This would make them safe from something like an airplane impact, Mowry says.

Others in the industry say SMRs will also be easier to maintain than existing nuclear plants. Full-scale nuclear facilities have many separately housed components—the reactor core, steam generator, pumping systems, and switchyard, to name a few—each of which requires maintenance personnel. In a SMR, all of these components are downsized and housed together.

To prevent the spread of nuclear radiation in the event of a catastrophe, the U.S Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) currently requires a 10-mile emergency evacuation zone around a nuclear plant. Mowry says the passive safety features of the SMR design will make it safe enough to reduce this zone to a half mile and to site future reactors closer to urban areas.

Not everyone agrees with this assessment. Edwin Lyman, senior scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists Global Security Program, said there is no reason why regulations should be put in place to accommodate SMRs. He said the point of a 10-mile emergency zone is to provide additional security in the event of an unforeseeable catastrophe, like the 2011 earthquake and tsunami-triggered disaster at Japan’s Fukushima plant. “The safety zone is a buffer so that in a worst case scenario, say you have a large radiological release like the one at Fukushima, you can protect the public from a disaster,” he said.

He points out that at Fukushima and after the 1986 Chernobyl disaster in Ukraine, contamination of food and liquids occurred farther than 100 miles from the accident sites.

“I simply don’t believe that you can justify shrinking those boundaries based on nuclear reactor designs that are just on paper,” he said.

Contrary to the view of the proponents, Lyman argues that housing vital reactor components close together could make a plant more vulnerable, because a single attack could be more destructive. “If a terrorist gained access to a SMR facility, a single explosive could potentially take out both the primary and backup safety systems,” he said.

Even if a SMR ends up being cheaper to build than a full-scale nuclear facility, some have doubts that the electricity it produces will be cheaper.

Lyman says the low price goes against economy of scale and banks on efficiencies in mass production and lenient safety regulations that have not been demonstrated or approved. “I think the best-case scenario is that electricity from SMRs will cost about the same as electricity from contemporary facilities,” he said. “This won’t be good enough to convince utilities to ramp up nuclear energy spending when there are cheaper alternatives like natural gas.”

He said the unproven economics could make it difficult for B&W and the TVA to raise funds for the actual construction of the Clinch River reactors that have an estimated price tag of nearly $2 billion. “The DOE grant only covers design development and licensing costs,” he said. “As far as I know, neither TVA nor any other entity has actually committed to build the Clinch River reactors.”

New Energy Secretary Moniz admitted that there are many unknowns, but said that the research was important to pursue. “I think the issue, which remains to be seen and can be determined only when we, in fact, do it, is to what extent will the economics of manufacturing lower the costs relative to larger reactors,” Moniz said at his confirmation hearing. “There is a great potential payout there, which goes on top of what are typically very attractive safety characteristics, for example, in the design of these reactors.” B&W is planning to submit its Clinch River reactor designs to the U.S Nuclear Regulatory Commission for approval sometime next year.

Dan Stout, senior manager for SMR Technology at the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), said TVA’s long-term hope is to deploy SMRs at the sites of retiring coal plants. But he said if the licensing requirements prove too exhaustive, and the technology isn’t cost-competitive for ratepayers, the project will be scratched.

Nevertheless, he said the team’s engineers, as well as TVA’s energy consumers, are optimistic about the project’s future.

“From the surveys we have done with our consumers, the people are very supportive of the project,” he says. “Our team believes that a SMR will be safe enough to warrant a smaller evacuation zone and will prove cost-effective.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.