Fat, sugar and trash may all fuel planes by 2050

Last year, a plane flew across the Atlantic fueled by fat and sugar for the first time, offering a glimpse of the airline industry’s future. One day, planes won’t burn petroleum — they’ll fly on a steady diet of fat, starch, sugar, trash, grass and the poop of a particular strain of bacteria found in rabbits’ guts, among other unfamiliar fuel sources.

At least, that’s the plan according to airlines such as American, Delta and United, which have set ambitious goals to zero out their carbon emissions by 2050.

Airplanes, which account for 2 percent of global carbon emissions, are far behind cars and power plants in switching away from fossil fuels. That’s because it’s hard to design a battery light enough and strong enough to power a commercial jet with electricity.

So for now, the most realistic way to dial back the airline industry’s emissions is to have planes burn cleaner fuels, known as sustainable aviation fuels (SAF). The problem is there’s nowhere near enough SAF to meet the airline industry’s fuel needs. Last year, the United States produced enough sustainable fuel to meet less than 0.2 percent of the airline industry’s jet fuel consumption.

The Biden administration has set a goal to raise that number to 100 percent by 2050. To get there, fuel refiners will have to embrace new and sometimes strange ways of producing jet fuel.

Each of these new fuel sources comes with its own set of trade-offs: Some will require years of research to develop, others have low ceilings on how much they can grow, and a few may create their own environmental problems. “There’s a really wide range,” said Nikita Pavlenko, who leads the fuels team at the nonprofit International Council for Clean Transportation.

But reducing planes’ carbon emissions will depend on wrangling all of these potential fuel sources because no single one of them can meet all the demand for jet fuel alone.

Here are some of the novel things refiners may turn into jet fuel in the coming years to meet the airline industry’s climate goals:

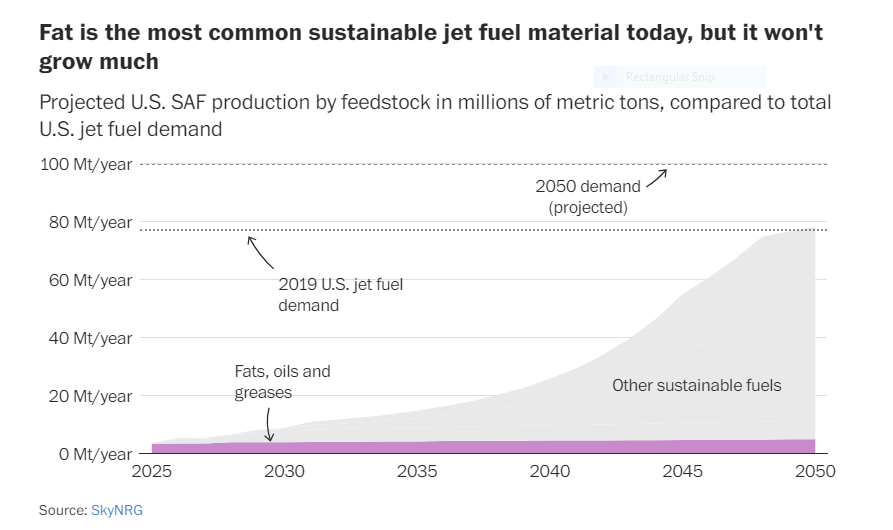

Nearly all sustainable jet fuel has so far been made from some form of fat, including used cooking oil, vegetable oil and animal fat. Refiners rearrange fat molecules into kerosene that can burn in jet engines.

Fat-based fuel is relatively cheap and — as long as it comes from waste products — produces few carbon emissions. But there isn’t enough to meet the airline industry’s thirst for fuel. The U.S. and Europe are already using pretty much the entire domestic supply of used cooking oil and importing additional waste fat from Asia to make biofuels for planes, cars and trucks, according to Pavlenko.

“We’re stuck with the quantities we already generate,” he said. “People aren’t going to be frying more food in response to biofuel policies.”

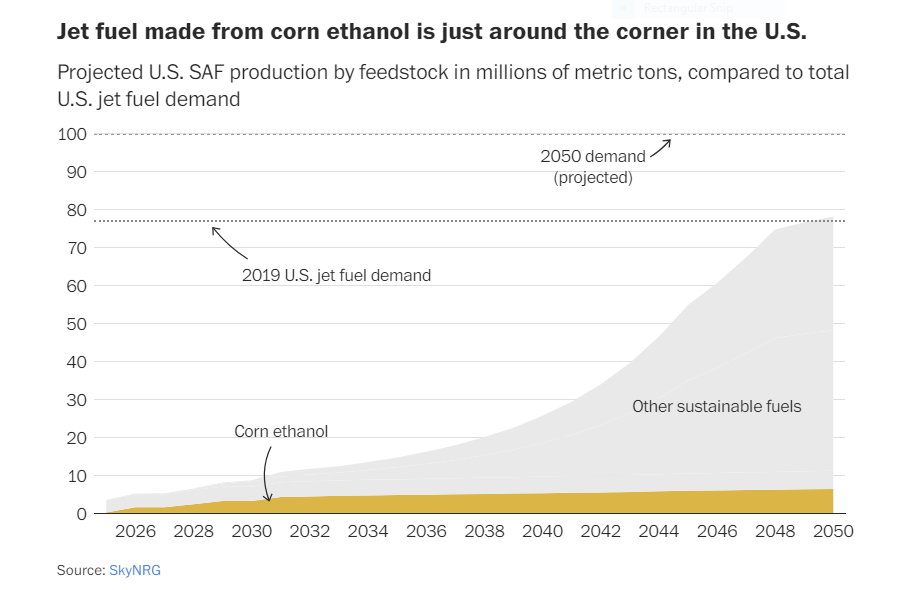

The next set of sustainable jet fuels to hit the U.S. market may be made from crops such as corn and sugar cane. Fuel refiners already ferment the starches and sugars in these crops into ethanol, which they mix into gasoline and diesel for cars and trucks.

Now, refiners are building factories that can turn ethanol into jet fuel. An alternative fuel start-up called LanzaJet, for example, opened the first factory in the world that can turn alcohol into jet fuel last week. That factory will make jet fuel using ethanol made from U.S. corn, Brazilian sugar cane and factory smoke that has been fermented into alcohol by bacteria.

The drawback is that fuel made from food crops probably won’t be as sustainable as fuel made from waste products. Farmland is limited, and expanding it to grow more crops for biofuels can lead to bad environmental consequences such as excess water usage and deforestation, which releases more carbon into the atmosphere.

To meet the U.S. airline industry’s entire fuel demand with corn ethanol, the country would have to grow 114 million acres of corn — an area bigger than California — according to the World Resources Institute.

“If you’re simply producing huge volumes of ethanol to meet the demands of aviation industry … you could run into a situation where you’re taking one step forward and two steps back,” said Mark Brownstein, who heads the energy transition team at the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund.

That’s why European regulations don’t count most biofuels made from food crops as “sustainable,” and jet fuel made from corn ethanol may not qualify for tax incentives under U.S. definitions, either — although U.S. regulators are changing those standards.

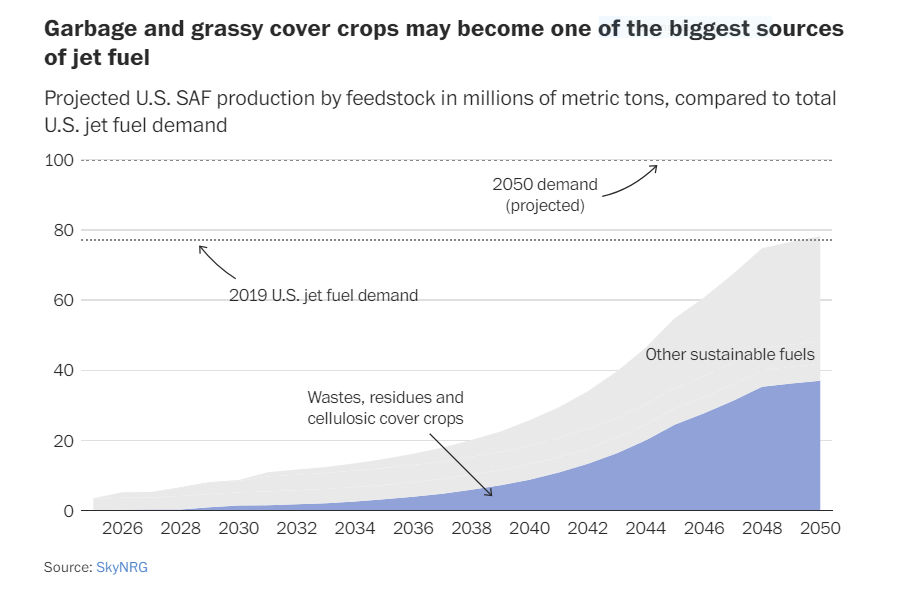

Two of the biggest future sources of jet fuel may be trash and grass.

As an alternative to corn or sugar cane ethanol, manufacturers are also developing ways to make jet fuel out of “cellulosic cover crops,” a category of grassy grains often grown on farms in between regular growing seasons to keep the soil healthy. Because they grow in the offseason, these plants wouldn’t compete with food crops for farmland, so they’d be more sustainable.

Some companies are also turning garbage into jet fuel, including a refiner called Fulcrum Bioenergy, which opened a waste-to-fuel plant outside of Reno, Nev., in 2022. But not all trash makes for good fuel material. Manufacturers have to sort out the useful bits, including paper, textiles and packaging materials, from the rest of the garbage. Fulcrum’s Reno factory sends about half the trash it takes in to landfills or recycling plants.

“You can hit a lot of snags if you have a really heterogenous, mixed set of things going into the factory,” said Pavlenko, “and trash is, unfortunately, extremely varied from batch to batch.”

Other forms of waste are more consistent. Fuel refiners can also make fuel out of agriculture waste, which includes the stalks, leaves and unpicked produce left in the field after crop harvesting or the husks and hulls leftover after food processing. Branches and bark leftover from logging and sawdust and wood chips leftover from lumbermills could also be turned into fuel.

Making jet fuel this way is expensive, and there aren’t many companies selling this type of fuel. “It’s still a relatively niche technology that’s being piloted in academia, so it’s not ready for prime time,” said Hartej Singh, an expert on sustainable aviation fuel at the Rocky Mountain Institute, clean energy think tank.

But as researchers perfect the process, these fuels may get cheaper and fill up more airplane fuel tanks.

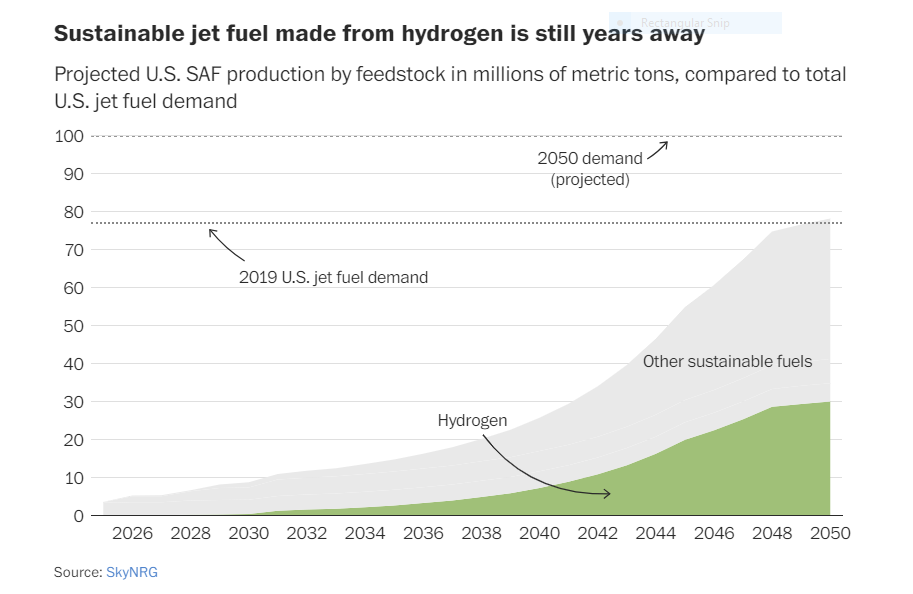

One day, companies could make jet fuel from little more than air, water and clean electricity. The key ingredient for this type of fuel is green hydrogen, which is produced by zapping water molecules apart into hydrogen and oxygen. If that electricity comes from clean power sources like wind or solar energy, it produces almost zero emissions. Refiners could combine the hydrogen with carbon captured from the air to make jet fuel.

“Because those are things that are theoretically limitless, they’re very, very scalable, but likely kind of expensive in the near term, and more technologically far away,” said Pavlenko.

Manufacturers probably won’t make much jet fuel from hydrogen until the 2030s, according to projections from SkyNRG, a sustainable aviation fuel manufacturer. But once production starts to ramp up, it could quickly become one of the biggest sources of sustainable fuel.

If all these fuels come online relatively fast, SkyNRG predicts they could meet current U.S. jet fuel demand by 2050 — but only if demand for flying stays flat. If the airline industry keeps growing at its current rate, sustainable fuels may not be able to catch up.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.