Earth's largest groundwater aquifers are past 'sustainability tipping points'

Humanity is rapidly depleting a third of the world’s largest groundwater aquifers, with the top three most stressed groundwater basins in the political hotspots of the Middle East, the border region between India and Pakistan, and the Murzuk-Djado Basin in northern Africa.

Making matters worse, researchers say in a pair of new studies, we don’t know how much water is left in these massive aquifers — which water resources scientists often refer to as Earth’s water savings accounts.

The studies come at a time when the worst drought on record since at least the 19th century is forcing California officials to curtail water use from even the politically powerful agricultural sector. Farmers in California’s Central Valley are slurping up so much groundwater that the state is actually sinking by up to a foot per year in some spots.

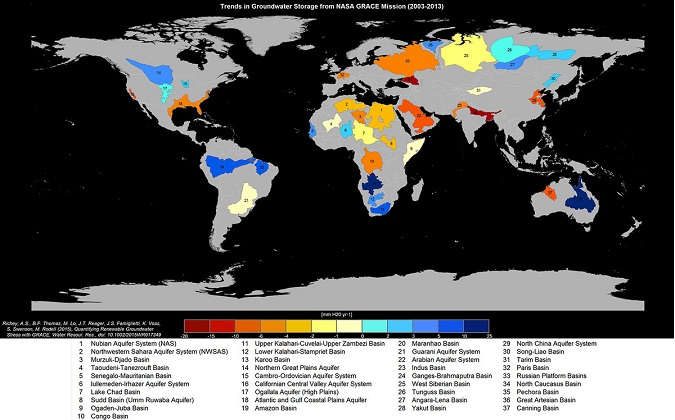

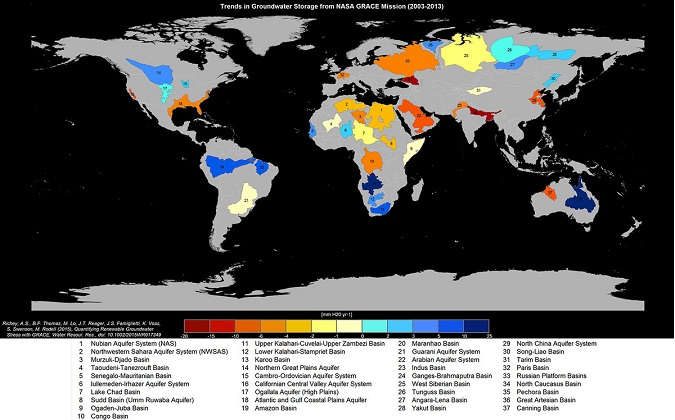

The studies come from the University of California at Irvine, and use data from NASA’s two Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment satellites, a system known by the acronym GRACE.

The picture these studies paint is a world in which we’re consuming water that has been stored by the Earth for hundreds, if not thousands, of years, and cannot be quickly replenished. We’re consuming it at ever faster rates, without knowing when to slow down.

The aquifers may be water savings accounts (or rather credit cards, since their overuse comes at a price). But they’re being treated like a checking account.

The fact that the majority of the world’s groundwater accounts “are past sustainability tipping points” was not known before, according to James Famiglietti, an author of both studies and a professor of Earth system science at the University of California, Irvine and senior water scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Such points are crossed when groundwater aquifers are no longer being replenished as quickly as they are being depleted, Famiglietti told Mashable in an interview.

Both studies appear Tuesday in the journal Water Resources Research. Famiglietti and his coauthors call for a global effort to determine how much water is left in the world’s most important aquifers.

“The message we want to get out there is this is really unacceptable,” he said. “We really better get on some kind of major exploration program.”

“What I am afraid of is people will say, ‘oh, we don’t know how much water there is, and maybe we have a ton,’” he said — but maybe we don’t. “The signs of stress are all there.”

Other studies, including previous work from Famiglietti, have focused on groundwater losses worldwide. But the new research is the first to characterize global groundwater loss rates using GRACE data.

For the first paper, Famiglietti and Alexandra Richey, a graduate student at UC-Irvine, examined the planet’s 37 largest aquifers during the decade of 2003 to 2013. They classified the eight that were worst off as overstressed, which for the study means that they had no natural replenishment to offset overuse.

Another five aquifers were either extremely or highly stressed, which means their loss rates were still much higher than replenishment rates — but they had some water flowing back into them, at least. “The human fingerprint on the water landscape has become very apparent as a result of this study,” Famiglietti told Mashable.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the worst-off aquifers are in the world’s driest areas, which draw heavily on underground water because of a lack of reliable surface water.

This includes a large swath of the politically unstable Middle East that draws from the Arabian Aquifer. That’s used by some 60 million people, including large parts of Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Yemen, where intense armed conflicts are ongoing.

Climate change and population growth are likely to exacerbate the problem of groundwater depletion, which is why national security experts have repeatedly sounded the alarm about global warming acting as a threat multiplier that will worsen already existing tensions.

“What happens when a highly stressed aquifer is located in a region with socioeconomic or political tensions that can’t supplement declining water supplies fast enough?” Richey said in a press release. “We’re trying to raise red flags now to pinpoint where active management today could protect future lives and livelihoods.”

Already, water stress may have helped trigger the brutal civil war in Syria, according to a widely reported study published in 2014.

The second-most overstressed aquifer identified in the studies is shared by India and Pakistan, two countries that have fought four major wars since the late 1940s, both of which are now armed with nuclear weapons.

In the second paper, the researchers compared their satellite data on groundwater loss rates to other data on groundwater availability. They found the world’s usable groundwater is an open question — one with important significance for society.

They concluded that the time to depletion of many aquifers is likely far less than previously estimated by researchers decades ago.

“We don’t actually know how much is stored in each of these aquifers. Estimates of remaining storage might vary from decades to millennia,” Richey said. “In a water-scarce society, we can no longer tolerate this level of uncertainty, especially since groundwater is disappearing so rapidly.”

Famiglietti, Richey and their coauthors are in favor of a global campaign to directly measure the amount of water stored in the world’s groundwater aquifers, which in many cases requires drilling to reach bedrock.

“I believe we need to explore the world’s aquifers as if they had the same value as oil reserves,” Famiglietti said in the release.

Making matters worse, researchers say in a pair of new studies, we don’t know how much water is left in these massive aquifers — which water resources scientists often refer to as Earth’s water savings accounts.

The studies come at a time when the worst drought on record since at least the 19th century is forcing California officials to curtail water use from even the politically powerful agricultural sector. Farmers in California’s Central Valley are slurping up so much groundwater that the state is actually sinking by up to a foot per year in some spots.

The studies come from the University of California at Irvine, and use data from NASA’s two Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment satellites, a system known by the acronym GRACE.

The picture these studies paint is a world in which we’re consuming water that has been stored by the Earth for hundreds, if not thousands, of years, and cannot be quickly replenished. We’re consuming it at ever faster rates, without knowing when to slow down.

The aquifers may be water savings accounts (or rather credit cards, since their overuse comes at a price). But they’re being treated like a checking account.

The fact that the majority of the world’s groundwater accounts “are past sustainability tipping points” was not known before, according to James Famiglietti, an author of both studies and a professor of Earth system science at the University of California, Irvine and senior water scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Such points are crossed when groundwater aquifers are no longer being replenished as quickly as they are being depleted, Famiglietti told Mashable in an interview.

Both studies appear Tuesday in the journal Water Resources Research. Famiglietti and his coauthors call for a global effort to determine how much water is left in the world’s most important aquifers.

“The message we want to get out there is this is really unacceptable,” he said. “We really better get on some kind of major exploration program.”

“What I am afraid of is people will say, ‘oh, we don’t know how much water there is, and maybe we have a ton,’” he said — but maybe we don’t. “The signs of stress are all there.”

Other studies, including previous work from Famiglietti, have focused on groundwater losses worldwide. But the new research is the first to characterize global groundwater loss rates using GRACE data.

For the first paper, Famiglietti and Alexandra Richey, a graduate student at UC-Irvine, examined the planet’s 37 largest aquifers during the decade of 2003 to 2013. They classified the eight that were worst off as overstressed, which for the study means that they had no natural replenishment to offset overuse.

Another five aquifers were either extremely or highly stressed, which means their loss rates were still much higher than replenishment rates — but they had some water flowing back into them, at least. “The human fingerprint on the water landscape has become very apparent as a result of this study,” Famiglietti told Mashable.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the worst-off aquifers are in the world’s driest areas, which draw heavily on underground water because of a lack of reliable surface water.

This includes a large swath of the politically unstable Middle East that draws from the Arabian Aquifer. That’s used by some 60 million people, including large parts of Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Yemen, where intense armed conflicts are ongoing.

Climate change and population growth are likely to exacerbate the problem of groundwater depletion, which is why national security experts have repeatedly sounded the alarm about global warming acting as a threat multiplier that will worsen already existing tensions.

“What happens when a highly stressed aquifer is located in a region with socioeconomic or political tensions that can’t supplement declining water supplies fast enough?” Richey said in a press release. “We’re trying to raise red flags now to pinpoint where active management today could protect future lives and livelihoods.”

Already, water stress may have helped trigger the brutal civil war in Syria, according to a widely reported study published in 2014.

The second-most overstressed aquifer identified in the studies is shared by India and Pakistan, two countries that have fought four major wars since the late 1940s, both of which are now armed with nuclear weapons.

In the second paper, the researchers compared their satellite data on groundwater loss rates to other data on groundwater availability. They found the world’s usable groundwater is an open question — one with important significance for society.

They concluded that the time to depletion of many aquifers is likely far less than previously estimated by researchers decades ago.

“We don’t actually know how much is stored in each of these aquifers. Estimates of remaining storage might vary from decades to millennia,” Richey said. “In a water-scarce society, we can no longer tolerate this level of uncertainty, especially since groundwater is disappearing so rapidly.”

Famiglietti, Richey and their coauthors are in favor of a global campaign to directly measure the amount of water stored in the world’s groundwater aquifers, which in many cases requires drilling to reach bedrock.

“I believe we need to explore the world’s aquifers as if they had the same value as oil reserves,” Famiglietti said in the release.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.