Drought Season Off to a Bad Start, Scientists Forecast Another Bleak Year

Drought conditions in more than half of the United States have slipped into a pattern that climatologists say is uncomfortably similar to the most severe droughts in recent U.S. history, including the 1930s Dust Bowl and the widespread 1950s drought.

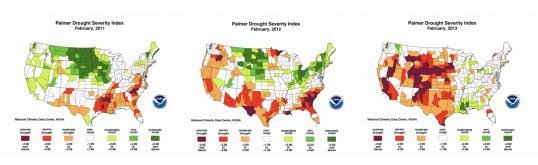

Drought conditions in more than half of the United States have slipped into a pattern that climatologists say is uncomfortably similar to the most severe droughts in recent U.S. history, including the 1930s Dust Bowl and the widespread 1950s drought.The 2013 drought season is already off to a worse start than in 2012 or 2011—a trend that scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) say is a good indicator, based on historical records, that the entire year will be drier than last year, even if spring and summer rainfall and temperatures remain the same. If rainfall decreases and temperatures rise, as climatologists are predicting will happen this year, the drought could be even more severe.

The federal researchers also say there is less than a 20 percent chance the drought will end in the next six months.

“There were certainly pockets of drought as we went into spring last year, but overall, the situation was much better than it is now,” said Tom Karl, a climatologist and director of NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center. “We are going to have to watch really closely … Last year was bad enough.”

In February, 54.2 percent of the contiguous United States experienced drought conditions, compared to 39 percent at the same time last year. Large swaths of South Dakota, Wyoming, Nebraska and Montana—which entered last year’s major agricultural growing season with very moist conditions—are now battling severe and extreme drought as farmers get ready to plant their spring crops.

The outlooks for rainfall and temperature are similarly bleak.

NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center forecast last week that Texas, Oklahoma and the Pacific Northwest will likely get less rainfall in 2013 than in 2012, and that the entire nation will experience a warmer summer than last year.

“Here in Texas, we’re worried about experiencing similar impacts on our agricultural industry that we had in 2011,” said John Nielsen-Gammon, the Texas State climatologist. “The fact that we’re starting off with water levels and reservoirs lower than they’ve been in decades just makes matters worse.”

NOAA has worked for years to find ways to predict when a drought will start and how long it will last. If climatologists had known that the Dust Bowl would stretch for nine years or that 1950s drought would last for five, farmers might have switched their agricultural practices, planted different crops, or used the remaining water more carefully.

By looking back at the environmental factors that helped ease or end historic droughts, researchers also have formed an idea of the weather conditions needed to stop a drought, said Mike Brewer, a climatologist who manages the National Climatic Data Center’s Drought Portal. But those predictions aren’t accurate beyond a six-month timeframe, because historical droughts can only tell them so much.

“Every drought has a different flavor,” Brewer said. “They form in different conditions and are controlled by different factors.”

The Dust Bowl in the 1930s, for instance, was caused by above-average temperatures and poor farming practices, said Karl. Farmers plowed their land too deep and too frequently, stripping away the plant life that held the soil together. Once the dirt became airborne, the dark particles absorbed incoming heat from the sun, stabilized the atmosphere and stopped the formation of rain-inducing thunderclouds.

Modern farming practices have reduced the dust, so that isn’t the problem this time around. What gives the current drought its own “flavor” is climate change, Karl said.

“We have a lot more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, so temperatures are warmer than they would have been in the 1930s,” he said. “These warmer temperatures increase evaporation, which makes it drier, which in turn makes it even warmer.”

The Dust Bowl and the 1950s drought aren’t necessarily the worse-case scenarios, said Nielsen-Gammon, the Texas climatologist. Tree ring records indicate that over the past 1,000 years, North America has suffered from droughts that lasted for decades and were much more severe than those in recent history.

“It just gives us a sense of what’s possible,” said Nielsen-Gammon.

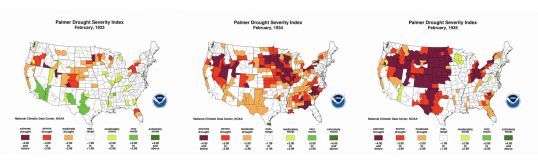

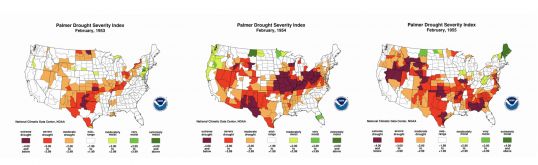

*** MAPS: Palmer Drought Severity Indices showing February drought conditions in consecutive years during the 1930s, 1950s and 2010s. The years 2011-2013 reveal worsening conditions year after year, a pattern that is similar to the devastating droughts of the 30s and 50s. Source: NOAA/National Climatic Data Center

1930s

1950s

2011-2013

Despite recent strides in drought predictions, Brewer and Karl said scientists still can’t determine whether we are in the climax or at the tail end of a drought—or if we’ve been thrust into a multi-decade drought—until years after rainfall has increased and temperatures have subsided.

If patterns from previous droughts are in fact being repeated now, the 2013 drought has the potential to seriously damage an already wounded agricultural system.

Last year marked the most severe and extensive drought in at least 25 years, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. It was also the hottest year on record for the United States. Nearly 80 percent of farmland experienced drought in 2012, with more than 2,000 counties designated disaster areas. By September 2012, 50 percent of the crops being harvested were in poor or very poor condition.

Last year’s damaged harvest is expected to raise food prices by as much as 4 percent in 2013, particularly products like beef, which suffered from a lack of available cattle feed and viable foraging options. Overall, the 2012 drought cost an estimated $150 billion in damage, as well as an estimated 0.5 to 1 percent drop in the U.S. gross domestic product.

The NOAA scientists hope their prediction that this year’s drought season is starting off worse than last year’s—and that it will last at least another six months—can help farmers make better decisions about what to plant. But Bob Young, the chief economist for the American Farm Bureau Federation, the nation’s largest farm organization, said that while the heads-up may influence some crop decisions, most farmers probably won’t pay attention to the scientific findings.

“They know what is going on in their own dirt,” Young said. “They tend to watch their own area specifically. Some might choose more soybean than corn since it is more drought tolerant, but overall, I don’t think it will change things much.”

Paul Bertels, vice president of production and utilization at the National Corn Growers Association, a major agricultural lobbying group, agreed.

“I don’t think they’re worrying,” said Bertels, who also runs a small farm outside St. Louis, Mo. “Forecasters also said March was supposed to be warm, and it wasn’t.”

One industry looking closely, albeit cautiously, at the early-season drought maps is the insurance business. Farmers have filed for a record $14.2 billion in crop insurance so far to cover losses from last year, with the federal government and private companies splitting the bill.

“Looking at these early drought estimates gives us some sense of how we should manage our reinsurance,” said Tim Weber, president of crop insurance for the Great American Insurance Group, one of the largest agricultural insurers in the country. “We don’t have the moisture reserves in the western Corn Belt that we’ve enjoyed in the past, and if we don’t get adequate rain in the spring, it could spell trouble.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.