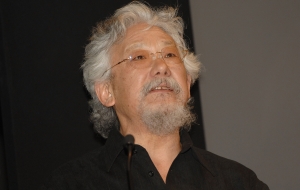

David Suzuki: The absurdity of endless economic growth

Have you noticed that we describe the market and economy as if they were living entities? The market is showing signs of stress. The economy is healthy. The economy is on life support.

Have you noticed that we describe the market and economy as if they were living entities? The market is showing signs of stress. The economy is healthy. The economy is on life support. Sometimes, we act as if the economy is larger than life. In the past, people trembled in fear of dragons, demons, gods, and monsters, sacrificing anything— virgins, money, newborn babies—to appease them. We know now that those fears were superstitious imaginings, but we have replaced them with a new behemoth: the economy.

Even stranger, economists believe this behemoth can grow forever. Indeed, the measure of how well a government or corporation is doing is its record of economic growth. But our home—the biosphere, or zone of air, water, and land where all life exists—is finite and fixed. It can’t grow. And nothing within such a world can grow indefinitely. In focusing on constant growth, we fail to ask the important questions. What is an economy for? Am I happier with all this stuff? How much is enough?

A timely new book by York University environmental economist Peter Victor, Managing Without Growth: Slower by Design, Not Disaster, addresses the absurdity of an economic system based on endless growth. Dr. Victor also shows that the concept of growth as an indispensable feature of economics is a recent phenomenon.

The economy is not a force of nature—some kind of immutable, infallible entity. We created it and, when cracks appear, it makes no sense to simply shovel on more money to keep it going. Because it’s a human invention, an economy is something we should be able to fix—but if we can’t, we should toss it out and replace it with something better.

This current economic crisis provides an opportunity to re-examine our priorities. For decades, scientists and environmentalists have been alarmed at global environmental degradation. Today, the oceans are depleted of fish while “dead zones”, immense islands of plastic, and acidification from dissolving carbon dioxide are having untold effects. We have altered the chemistry of the atmosphere with our emissions, causing the planet to heat up, and have cleared land of forests, along with hundreds of thousands of species. Using air, water, and soil as dumps for our industrial wastes, we have poisoned ourselves.

For the first time in four billion years of life on Earth, one species has become so powerful and plentiful that it is altering the physical, chemical, and biological features of the planet on a geological scale. And so we have to ask, “What is the collective impact of everyone in the world?” We’ve never had to do that before and it’s difficult. Even when we do contemplate our global effects, we have no mechanism to respond as one species to the crises.

Driving much of this destructive activity is the economy itself. Years ago, during a heated debate about clear-cutting, a forest-company CEO yelled at me, “Listen, Suzuki: Are tree huggers like you willing to pay to protect those trees? Because if you’re not, they don’t have any value until someone cuts them down!” I was dumbstruck with the realization that in our economic system, he was correct.

You see, as long as that forest is intact, the plants photosynthesize and remove carbon dioxide from the air while putting oxygen back—not a bad service for animals like us that depend on clean air. However, economists dismiss this as an “externality”. What they mean is that photosynthesis is not relevant to the economic system they’ve created!

Those tree roots cling to the soil, so when it rains the soil doesn’t erode into the river and clog the salmon-spawning gravels, another externality to economists. The trees pump hundreds of thousands of litres of water out of the soil, transpiring it into the air and modulating weather and climate—an externality. The forest provides habitat to countless species of bacteria, fungi, insects, mammals, amphibians, and birds—externality. So all the things an intact ecosystem does to keep the planet vibrant and healthy for animals like us are simply ignored in our economy. No wonder futurist Hazel Henderson describes conventional economics as “a form of brain damage”.

Nature’s services keep the planet habitable for animals like us and must become an integral component of a new economic structure. We must get off this suicidal focus on endless, mindless growth.

Take David Suzuki’s Nature Challenge and learn more at www.davidsuzuki.org/.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.