Customers Could Pay $2.5 Billion for Nuclear Plants That Never Get Built

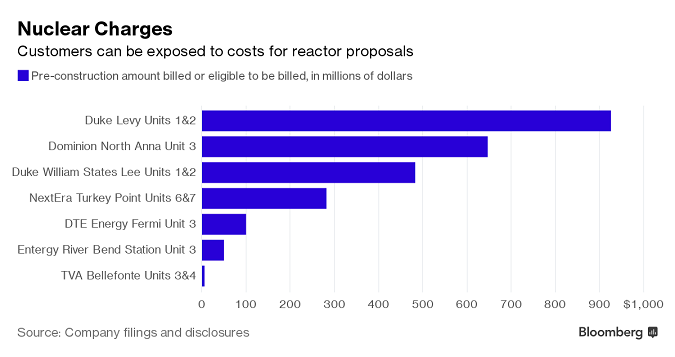

U.S. electricity consumers could end up paying more than $2.5 billion for nuclear plants that never get built.

Utilities including Duke Energy Corp., Dominion Resources Inc. and NextEra Energy Inc. are being allowed by regulators to charge $1.7 billion for reactors that exist only on paper, according to company disclosures and regulatory filings. Duke and Dominion could seek approval to have ratepayers pony up at least another $839 million, the filings show.

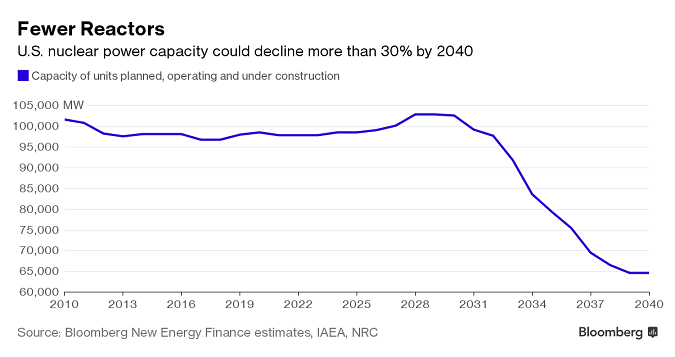

The practice comes as power-plant operators are increasingly turning to cheaper natural gas and carbon-free renewables as their fuels of choice. The growth of these alternatives is sparking a backlash from consumers and environmentalists who are challenging the need for more nuclear power in arguments that have spilled into courtrooms, regulatory proceedings and legislative agendas.

“Anything that hasn’t gotten off the ground yet isn’t getting built,” said Greg Gordon, a utility analyst at Evercore ISI, a New York-based investment advisory firm. “There is no economic rationale for it.”

Only two of 18 nuclear projects proposed since 2007 are under construction. Those units, being built by Southern Co. in Georgia and Scana Corp. in South Carolina, are billions of dollars over budget and years behind schedule. In the meantime, the price of natural gas has dropped 38 percent since 2010. It’s now used to generate more than a third of the nation’s power, up from 24 percent six years ago.

Utilities that are moving forward with their nuclear plans say they want to preserve the option to build if market or regulatory conditions change. Nuclear power offers around-the-clock, carbon-free electricity that becomes more valuable if federal rules limiting greenhouse gases take hold, the utilities say.

“One way to mitigate these risks is to spend money now, so that you have a license to build a nuclear plant if and when you need to,” said Richard Myers, vice president of the Nuclear Energy Institute, an industry trade group.

Critics of policies that allow utilities to bill for planned reactors say they’re likely unneeded, and the practice shifts upfront financial risks from shareholders to customers.

“The rich get richer and the ratepayers get poorer,” said Mark Cooper, a research fellow at Vermont Law School who submitted testimony in July opposing Dominion’s planned reactor in Virginia on behalf of the Virginia Citizens Consumer Council.

Duke fell 0.2 percent to $84.55 at 9:50 am in New York. NextEra fell 0.3 percent to $125.72. Dominion fell 0.4 percent to $74.70.

Nuke Spending

Money collected from ratepayers so far has gone for items including federal licensing, permitting, land purchases, financing and equipment. Nuclear developers have sunk at least $1.2 billion of their own cash into proposals where they aren’t allowed or won’t ask to recover expenses from consumers, the disclosures and filings show.

At least seven states including Florida allow utilities to collect nuclear licensing and planning costs from customers before any construction begins.

In Virginia and Florida, utilities are seeing increased scrutiny of their plans. The Virginia attorney general has raised concerns about the rising expense of Dominion’s proposed new reactor at its North Anna facility, estimating the total cost at $19 billion.

“If Dominion proceeds on this ruinous path, it will extract $6 billion to $12 billion in needlessly higher energy bills,” said Irene Leech, president of the Virginia Citizens Consumer Council.

Shareholder Vote

In May, Dominion faced a shareholder resolution that would have required the company to analyze the financial risks of not getting regulatory approval for the new reactor. The proposal didn’t pass.

Dominion intends to spend $647 million to get a federal nuclear license next year and $302 million of that has already been collected from ratepayers.

“We’ve done a lot of work for licensing North Anna 3, which is prudent and valuable to our customers to maintain a diverse, carbon-free baseload source of electricity,” said Richard Zuercher, a Dominion spokesman.

In Florida, multiple efforts in the state legislature to repeal a law that allows advanced collection of nuclear costs have failed.

“I just never thought nuclear power plants made sense,” said Florida State Representative Michelle Rehwinkel Vasilinda, a Democrat, who has proposed bills to overturn the advance fee collection law.

In February, a federal lawsuit was filed on behalf of consumers that seeks to overturn the Florida statute and recover fees charged by Duke and NextEra for nuclear power plants that might not be completed. The suit alleges the companies overcharged customers for projects including Duke’s proposal for two reactors in Levy County and NextEra’s plan for two units at Turkey Point.

Legal Action

Duke and NextEra have asked a judge to dismiss the suit. Four other lawsuits challenging the state law have been rejected by Florida courts, said Rita Sipe, a Duke spokeswoman. The suits were filed on behalf of an environmental group and customers, according to court records.

As part of an agreement with Florida regulators in 2013, Duke was allowed to collect $926 million from customers to cover expenses including land and equipment purchases for its Levy facility, Sipe said. Work on the construction site has stopped.

The company is pursuing a federal license for the plant but won’t charge customers for the costs of doing so, said Chris Fallon, vice president for nuclear development for Duke. The company sees the option to build as a hedge against pending environmental rules and possible natural gas price hikes, Fallon said.

Carolina Plants

Separately, Duke said it hasn’t decided if it will ask regulators for permission to collect $494 million in planning expenses for two proposed reactors in South Carolina.

Regulators have allowed NextEra to recoup $282 million of federal licensing costs for two new units at its Turkey Point facility, said Peter Robbins, a company spokesman. NextEra doesn’t see getting a license until the end of 2017 and will delay pre-construction work until at least 2020, Robbins said.

Critics say the issue is still whether companies should be allowed to bill for facilities that may never get finished.

“Customers can get stuck with the bill long before a single kilowatt of power is produced and may never recoup anything if the nuclear project is later abandoned,” said Jeremiah Lambert, an energy attorney and author of “The Power Brokers,” a history of the electric power industry.

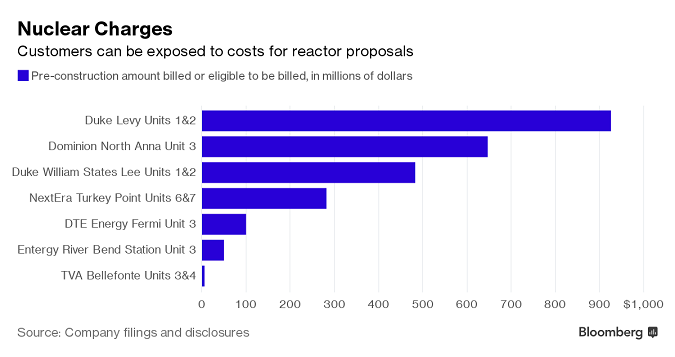

Utilities including Duke Energy Corp., Dominion Resources Inc. and NextEra Energy Inc. are being allowed by regulators to charge $1.7 billion for reactors that exist only on paper, according to company disclosures and regulatory filings. Duke and Dominion could seek approval to have ratepayers pony up at least another $839 million, the filings show.

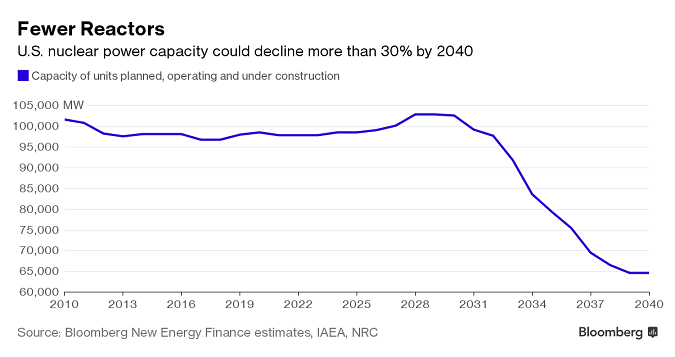

The practice comes as power-plant operators are increasingly turning to cheaper natural gas and carbon-free renewables as their fuels of choice. The growth of these alternatives is sparking a backlash from consumers and environmentalists who are challenging the need for more nuclear power in arguments that have spilled into courtrooms, regulatory proceedings and legislative agendas.

“Anything that hasn’t gotten off the ground yet isn’t getting built,” said Greg Gordon, a utility analyst at Evercore ISI, a New York-based investment advisory firm. “There is no economic rationale for it.”

Only two of 18 nuclear projects proposed since 2007 are under construction. Those units, being built by Southern Co. in Georgia and Scana Corp. in South Carolina, are billions of dollars over budget and years behind schedule. In the meantime, the price of natural gas has dropped 38 percent since 2010. It’s now used to generate more than a third of the nation’s power, up from 24 percent six years ago.

Utilities that are moving forward with their nuclear plans say they want to preserve the option to build if market or regulatory conditions change. Nuclear power offers around-the-clock, carbon-free electricity that becomes more valuable if federal rules limiting greenhouse gases take hold, the utilities say.

“One way to mitigate these risks is to spend money now, so that you have a license to build a nuclear plant if and when you need to,” said Richard Myers, vice president of the Nuclear Energy Institute, an industry trade group.

Critics of policies that allow utilities to bill for planned reactors say they’re likely unneeded, and the practice shifts upfront financial risks from shareholders to customers.

“The rich get richer and the ratepayers get poorer,” said Mark Cooper, a research fellow at Vermont Law School who submitted testimony in July opposing Dominion’s planned reactor in Virginia on behalf of the Virginia Citizens Consumer Council.

Duke fell 0.2 percent to $84.55 at 9:50 am in New York. NextEra fell 0.3 percent to $125.72. Dominion fell 0.4 percent to $74.70.

Nuke Spending

Money collected from ratepayers so far has gone for items including federal licensing, permitting, land purchases, financing and equipment. Nuclear developers have sunk at least $1.2 billion of their own cash into proposals where they aren’t allowed or won’t ask to recover expenses from consumers, the disclosures and filings show.

At least seven states including Florida allow utilities to collect nuclear licensing and planning costs from customers before any construction begins.

In Virginia and Florida, utilities are seeing increased scrutiny of their plans. The Virginia attorney general has raised concerns about the rising expense of Dominion’s proposed new reactor at its North Anna facility, estimating the total cost at $19 billion.

“If Dominion proceeds on this ruinous path, it will extract $6 billion to $12 billion in needlessly higher energy bills,” said Irene Leech, president of the Virginia Citizens Consumer Council.

Shareholder Vote

In May, Dominion faced a shareholder resolution that would have required the company to analyze the financial risks of not getting regulatory approval for the new reactor. The proposal didn’t pass.

Dominion intends to spend $647 million to get a federal nuclear license next year and $302 million of that has already been collected from ratepayers.

“We’ve done a lot of work for licensing North Anna 3, which is prudent and valuable to our customers to maintain a diverse, carbon-free baseload source of electricity,” said Richard Zuercher, a Dominion spokesman.

In Florida, multiple efforts in the state legislature to repeal a law that allows advanced collection of nuclear costs have failed.

“I just never thought nuclear power plants made sense,” said Florida State Representative Michelle Rehwinkel Vasilinda, a Democrat, who has proposed bills to overturn the advance fee collection law.

In February, a federal lawsuit was filed on behalf of consumers that seeks to overturn the Florida statute and recover fees charged by Duke and NextEra for nuclear power plants that might not be completed. The suit alleges the companies overcharged customers for projects including Duke’s proposal for two reactors in Levy County and NextEra’s plan for two units at Turkey Point.

Legal Action

Duke and NextEra have asked a judge to dismiss the suit. Four other lawsuits challenging the state law have been rejected by Florida courts, said Rita Sipe, a Duke spokeswoman. The suits were filed on behalf of an environmental group and customers, according to court records.

As part of an agreement with Florida regulators in 2013, Duke was allowed to collect $926 million from customers to cover expenses including land and equipment purchases for its Levy facility, Sipe said. Work on the construction site has stopped.

The company is pursuing a federal license for the plant but won’t charge customers for the costs of doing so, said Chris Fallon, vice president for nuclear development for Duke. The company sees the option to build as a hedge against pending environmental rules and possible natural gas price hikes, Fallon said.

Carolina Plants

Separately, Duke said it hasn’t decided if it will ask regulators for permission to collect $494 million in planning expenses for two proposed reactors in South Carolina.

Regulators have allowed NextEra to recoup $282 million of federal licensing costs for two new units at its Turkey Point facility, said Peter Robbins, a company spokesman. NextEra doesn’t see getting a license until the end of 2017 and will delay pre-construction work until at least 2020, Robbins said.

Critics say the issue is still whether companies should be allowed to bill for facilities that may never get finished.

“Customers can get stuck with the bill long before a single kilowatt of power is produced and may never recoup anything if the nuclear project is later abandoned,” said Jeremiah Lambert, an energy attorney and author of “The Power Brokers,” a history of the electric power industry.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.