Coal's slipping grip: Death of a Georgia coal plant. PART TWO!

The smokestacks, more than 800 feet tall, barely peek from behind the tall pines just across from Chester Allen’s farm, but to him the damage from Plant Yates’ coal is plain to see.

“Dang-near everything rusts out early over here,” said Allen, as he walked with his dog, Bogey, past a rusty disc harrow on the farm where he’s lived for more than thirty years. His drag, steel gates, fence posts, barn roof – all rusted. Equipment this new – 15 years old, he reckons – shouldn’t be this rusty.

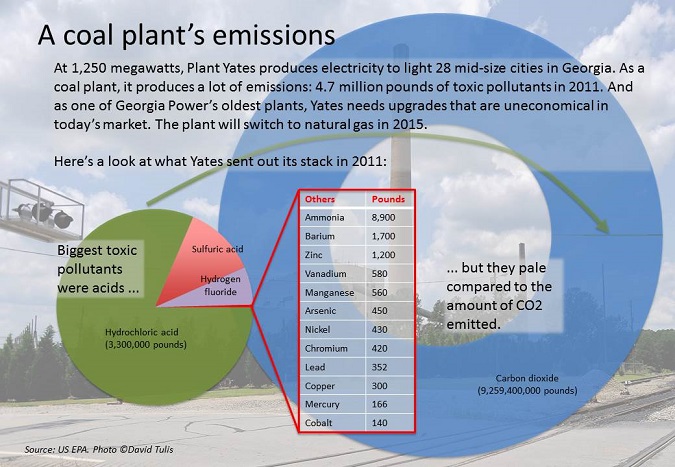

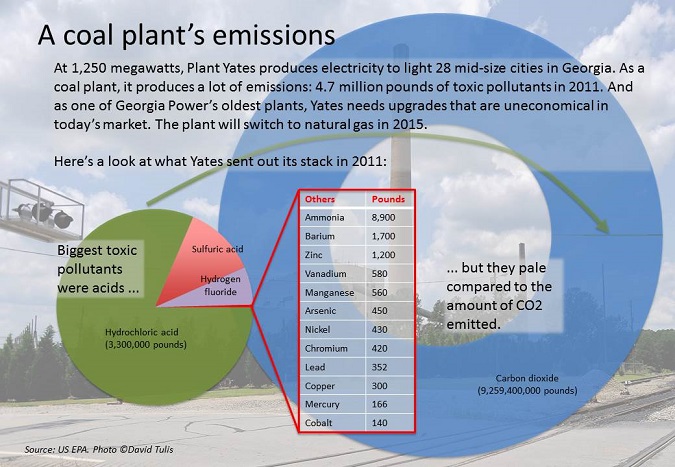

And maybe they wouldn’t be, but for the fact that Plant Yates, a coal-fired plant that opened in 1950, spewed 3.4 million pounds of corrosive acids into the air in 2011.

The impact of Yates and other coal plants in Georgia goes far beyond some rusty farm equipment. Emissions of hydrochloric and sulfuric acids, soot, smog-causing gases and mercury take a health toll. Coal trains and ash ponds weigh on the land. But soon Sargent and two other communities in rural Georgia will get a reprieve.

Forced by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to meet new pollution rules, Georgia Power will shutter the coal and oil burners at Plant Yates and two other plants. Updating the facilities, the utility says, is too expensive so the plants are being switched to natural gas.

Around the country, about 600 power plants must be closed or retooled in the next two years, the result of EPA rules issued in 2011 that clamped down on coal-fired pollution.

In addition, last week President Obama announced plans to limit carbon pollution from new and existing power plants, a measure likely to prompt even more changes at coal-fired plants, including Georgia Power’s eight. The Southeast is one of the nation’s most coal-dependent regions.

There is a cost to the cleaner air that comes from shutting down these coal plants. Poor communities may breathe easier as the emissions leave town, but with them goes tax revenues and jobs. In the impoverished communities near Georgia’s coal plants, as in many communities around the country, the health benefits of nixing coal aren’t as obvious as the lost economic opportunities. Pollution will drop, but taxes might rise. Residents’ health might get better, but the job market in their towns will be worse.

These poor communities are trapped in coal’s Catch-22.

Rural Georgia hard-hit

Around the corner from Allen’s yard, rust covers cars and chicken coops in the beat-up yards on Robinson Road. Down the way, five guys are drinking beer and working on a race car in the middle of a weekday. Across the street, a house is crumbling.

About 40 miles southwest of Atlanta, this is a hard-hit part of Georgia, no question.

Yates released 4.7 million pounds of toxic chemicals into the air, land and water in 2011, according to the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory database. It also emitted 33,400 tons of nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide, which are linked to asthma attacks and other respiratory problems. And it sent 4.2 million tons of carbon dioxide skyward, the equivalent to 824,000 automobiles.

A consulting firm hired by a Boston-based environmental advocacy group estimated that soot from Yates is responsible for 186 asthma deaths and hospitalizations per year, for instance.

Coweta County, home to Plant Yates, has lower rates of asthma-related emergency room visits than the state, according to the Georgia Division of Public Health. But federal regulators say Yates violates the national health standard for fine particles, which can lodge in lungs and trigger heart attacks and respiratory disease. The county also exceeds the federal standard for ozone, the main ingredient of smog.

Pollution will drop, but taxes might rise. Residents’ health might get better, but the job market in their towns will be worse.Yates also has been in violation of a state clean air plan for almost three years. Plant Kraft, another Georgia Power operation near Savannah slated for closure, has a history of “high priority violations” of the Clean Air Act dating back to at least 2010.

“Those communities and downwind areas have been suffering for a long time from the pollution from these plants,” said Jenna Garland, spokesperson for the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign in the Southeast.

The EPA rules require new and existing coal- and oil-fired plants to reduce air pollutants – including mercury, arsenic, chromium, nickel, hydrochloric acid and hydrofluoric acid, among others – by 2015. Fine particles and sulfur dioxide emissions also must be reduced.

Nationwide, 40 percent of all coal-fired burners covered by the new standards will need upgraded pollution controls, the EPA estimates.

Those upgrades will cost utilities $9.6 billion, but the health benefits in 2016 alone from the reduced pollution range from $37 billion to $90 billion, according to the EPA.

For Georgia Power, the cost in plant upgrades is too steep. The company plans to decertify the units by April 16, 2015, when the standards kick in. Two of the seven burners at Yates will stay open, switching to natural gas. Two other coal plants – Plant Branch near Milledgeville and Plant Kraft near Savannah – and one oil-fired plant– Plant McManus near Brunswick – will go dark.

Coal brought jobs, tax revenues

For communities that have felt fossil fuel’s heavy hand for decades, the change will be sweeping.

All four have also come to depend on the jobs and tax revenue the plants have brought, though it hasn’t been a fair trade: Plant Yates has brought jobs and tax revenue to Sargent, but little other economic growth has come to the nearby neighborhoods. The areas surrounding Georgia’s soon-to-close coal units are some of the poorest in the state. The average per capita income within three miles of Plant Yates is $18,720.

A consulting firm estimated that soot from Yates is responsible for 186 asthma deaths and hospitalizations per year.Near Plant Branch, ranked as the 10th dirtiest coal plant in the nation in 2011 by the Natural Resources Defense Council, the average income within three miles is $22,702. For Savannah’s Plant Kraft, also built in the 1950s, it’s $16,348. Both are slated for closure.

Georgia’s average per capita income is $25,400.

No jobs will be lost as the company weans itself off coal, Georgia Power spokesman Mark Williams said. But 480 employees will either be relocated or given early retirement. The company realizes that there will be impacts on these communities. “But we have to do what’s in the best interest of our customers,” he added. “We have to do whatever we can to make sure that electricity is reliable and affordable.”

Billy Webster is the county commissioner for Putnam County, home of Plant Branch. The self-described conservative and tree-hugger said that no one near the plant, on the banks of Lake Sinclair in middle Georgia, likes the pollution from coal, but this already-poor area will have to scramble to make up for lost tax income. Tax increases are looming for the county’s 21,000 residents.

“People are coming to the realization that this is going to be devastating,” Webster said. “In this little community, it’s really hitting us the hardest.”

In Coweta County, Yates paid upwards of $3.5 million in property taxes in 2012, 12 percent of the county’s take that year, according to the county budget. Plant Branch paid Putnam County about $1 million in 2012, 14 percent of the county’s property tax revenue.

Dropping the coal- and oil-fired burners at the four power plants means a loss of 2,061 megawatts of energy, according to Georgia Power. The utility will make up that capacity with three new natural gas units that recently came online, as well as through energy efficiency, new solar investments and slower economic growth.

Additional energy capacity will come from two new reactors at Plant Vogtle, a nuclear power plant in eastern Georgia, near the South Carolina border, that Georgia Power owns jointly with Oglethorpe Power Corp., the Municipal Electric Authority of Georgia and Dalton Utilities. Vogtle is the nation’s first new nuclear construction in decades. The new reactors are expected to open in 2017, but the construction has been plagued by delays and cost overruns.

Other Georgia Power-owned coal-fired units are already installing new environmental controls to meet the EPA’s new pollution standards. And in Georgia’s communities that are abandoning coal, folks are wondering why their plants are going dark while others are being upgraded.

Down on Robinson Road, in Chester Allen’s rusted-out neighborhood, Justin Anderson looks up from his beer and the race car. Despite Georgia Power’s promise that no jobs will be lost, some folks have already been let go from Plant Yates, he said.

“A couple of our good friends used to work there,” said Anderson, who grew up across from Plant Yates. “It sucks for them.”

“Dang-near everything rusts out early over here,” said Allen, as he walked with his dog, Bogey, past a rusty disc harrow on the farm where he’s lived for more than thirty years. His drag, steel gates, fence posts, barn roof – all rusted. Equipment this new – 15 years old, he reckons – shouldn’t be this rusty.

And maybe they wouldn’t be, but for the fact that Plant Yates, a coal-fired plant that opened in 1950, spewed 3.4 million pounds of corrosive acids into the air in 2011.

The impact of Yates and other coal plants in Georgia goes far beyond some rusty farm equipment. Emissions of hydrochloric and sulfuric acids, soot, smog-causing gases and mercury take a health toll. Coal trains and ash ponds weigh on the land. But soon Sargent and two other communities in rural Georgia will get a reprieve.

Forced by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to meet new pollution rules, Georgia Power will shutter the coal and oil burners at Plant Yates and two other plants. Updating the facilities, the utility says, is too expensive so the plants are being switched to natural gas.

Around the country, about 600 power plants must be closed or retooled in the next two years, the result of EPA rules issued in 2011 that clamped down on coal-fired pollution.

In addition, last week President Obama announced plans to limit carbon pollution from new and existing power plants, a measure likely to prompt even more changes at coal-fired plants, including Georgia Power’s eight. The Southeast is one of the nation’s most coal-dependent regions.

There is a cost to the cleaner air that comes from shutting down these coal plants. Poor communities may breathe easier as the emissions leave town, but with them goes tax revenues and jobs. In the impoverished communities near Georgia’s coal plants, as in many communities around the country, the health benefits of nixing coal aren’t as obvious as the lost economic opportunities. Pollution will drop, but taxes might rise. Residents’ health might get better, but the job market in their towns will be worse.

These poor communities are trapped in coal’s Catch-22.

Rural Georgia hard-hit

Around the corner from Allen’s yard, rust covers cars and chicken coops in the beat-up yards on Robinson Road. Down the way, five guys are drinking beer and working on a race car in the middle of a weekday. Across the street, a house is crumbling.

About 40 miles southwest of Atlanta, this is a hard-hit part of Georgia, no question.

Yates released 4.7 million pounds of toxic chemicals into the air, land and water in 2011, according to the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory database. It also emitted 33,400 tons of nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide, which are linked to asthma attacks and other respiratory problems. And it sent 4.2 million tons of carbon dioxide skyward, the equivalent to 824,000 automobiles.

A consulting firm hired by a Boston-based environmental advocacy group estimated that soot from Yates is responsible for 186 asthma deaths and hospitalizations per year, for instance.

Coweta County, home to Plant Yates, has lower rates of asthma-related emergency room visits than the state, according to the Georgia Division of Public Health. But federal regulators say Yates violates the national health standard for fine particles, which can lodge in lungs and trigger heart attacks and respiratory disease. The county also exceeds the federal standard for ozone, the main ingredient of smog.

Pollution will drop, but taxes might rise. Residents’ health might get better, but the job market in their towns will be worse.Yates also has been in violation of a state clean air plan for almost three years. Plant Kraft, another Georgia Power operation near Savannah slated for closure, has a history of “high priority violations” of the Clean Air Act dating back to at least 2010.

“Those communities and downwind areas have been suffering for a long time from the pollution from these plants,” said Jenna Garland, spokesperson for the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign in the Southeast.

The EPA rules require new and existing coal- and oil-fired plants to reduce air pollutants – including mercury, arsenic, chromium, nickel, hydrochloric acid and hydrofluoric acid, among others – by 2015. Fine particles and sulfur dioxide emissions also must be reduced.

Nationwide, 40 percent of all coal-fired burners covered by the new standards will need upgraded pollution controls, the EPA estimates.

Those upgrades will cost utilities $9.6 billion, but the health benefits in 2016 alone from the reduced pollution range from $37 billion to $90 billion, according to the EPA.

For Georgia Power, the cost in plant upgrades is too steep. The company plans to decertify the units by April 16, 2015, when the standards kick in. Two of the seven burners at Yates will stay open, switching to natural gas. Two other coal plants – Plant Branch near Milledgeville and Plant Kraft near Savannah – and one oil-fired plant– Plant McManus near Brunswick – will go dark.

Coal brought jobs, tax revenues

For communities that have felt fossil fuel’s heavy hand for decades, the change will be sweeping.

All four have also come to depend on the jobs and tax revenue the plants have brought, though it hasn’t been a fair trade: Plant Yates has brought jobs and tax revenue to Sargent, but little other economic growth has come to the nearby neighborhoods. The areas surrounding Georgia’s soon-to-close coal units are some of the poorest in the state. The average per capita income within three miles of Plant Yates is $18,720.

A consulting firm estimated that soot from Yates is responsible for 186 asthma deaths and hospitalizations per year.Near Plant Branch, ranked as the 10th dirtiest coal plant in the nation in 2011 by the Natural Resources Defense Council, the average income within three miles is $22,702. For Savannah’s Plant Kraft, also built in the 1950s, it’s $16,348. Both are slated for closure.

Georgia’s average per capita income is $25,400.

No jobs will be lost as the company weans itself off coal, Georgia Power spokesman Mark Williams said. But 480 employees will either be relocated or given early retirement. The company realizes that there will be impacts on these communities. “But we have to do what’s in the best interest of our customers,” he added. “We have to do whatever we can to make sure that electricity is reliable and affordable.”

Billy Webster is the county commissioner for Putnam County, home of Plant Branch. The self-described conservative and tree-hugger said that no one near the plant, on the banks of Lake Sinclair in middle Georgia, likes the pollution from coal, but this already-poor area will have to scramble to make up for lost tax income. Tax increases are looming for the county’s 21,000 residents.

“People are coming to the realization that this is going to be devastating,” Webster said. “In this little community, it’s really hitting us the hardest.”

In Coweta County, Yates paid upwards of $3.5 million in property taxes in 2012, 12 percent of the county’s take that year, according to the county budget. Plant Branch paid Putnam County about $1 million in 2012, 14 percent of the county’s property tax revenue.

Dropping the coal- and oil-fired burners at the four power plants means a loss of 2,061 megawatts of energy, according to Georgia Power. The utility will make up that capacity with three new natural gas units that recently came online, as well as through energy efficiency, new solar investments and slower economic growth.

Additional energy capacity will come from two new reactors at Plant Vogtle, a nuclear power plant in eastern Georgia, near the South Carolina border, that Georgia Power owns jointly with Oglethorpe Power Corp., the Municipal Electric Authority of Georgia and Dalton Utilities. Vogtle is the nation’s first new nuclear construction in decades. The new reactors are expected to open in 2017, but the construction has been plagued by delays and cost overruns.

Other Georgia Power-owned coal-fired units are already installing new environmental controls to meet the EPA’s new pollution standards. And in Georgia’s communities that are abandoning coal, folks are wondering why their plants are going dark while others are being upgraded.

Down on Robinson Road, in Chester Allen’s rusted-out neighborhood, Justin Anderson looks up from his beer and the race car. Despite Georgia Power’s promise that no jobs will be lost, some folks have already been let go from Plant Yates, he said.

“A couple of our good friends used to work there,” said Anderson, who grew up across from Plant Yates. “It sucks for them.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.