Climate change in Antarctica: Ice shelf collapse, stunning warmth

In early March, analysts at the U.S. National Ice Center began to notice changes along the eastern coast of Antarctica.

In early March, analysts at the U.S. National Ice Center began to notice changes along the eastern coast of Antarctica.

First, a large piece of ice, some 13 nautical miles in length, broke off the remnants of an area known as the Glenzer ice shelf. Ice shelves are sections of glacial ice that extend off land and rest on the ocean, and occasionally “calve,” or break apart, to produce icebergs.

Although it’s less common for such an event to take place on the eastern side of Antarctica – the western side is far more dynamic and tends to be the focus of scientists who study glaciers – it is by no means unprecedented, says Christopher Readinger, the Ice Center’s lead Antarctic ice analyst.

He quickly put out a memo, informing sailors and scientists that a newly named iceberg, C-37, was now floating in what is already considered one of Earth’s most harrowing maritime environments.

But then, a week later, something else happened.

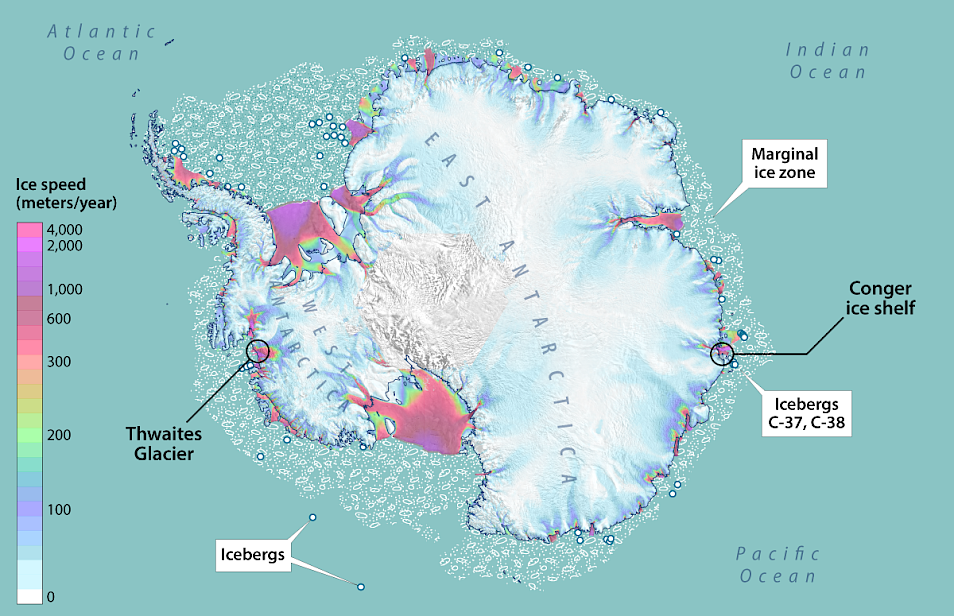

The ice shelf adjacent to Glenzer, a New York City-size mass called the Conger ice shelf, collapsed completely – the first time this had happened in East Antarctica since scientists began using satellites to record such events.

The collapse came around the same time as a stunning heat wave in the region, which had included temperatures reaching nearly 70 degrees Fahrenheit above normal. (This pushed the temperature to a relatively balmy 11 degrees F, compared with the typical 56 below zero.) Some scientists have described it as Earth’s most extreme heat wave ever recorded.

Mr. Readinger sent out another report and named a new iceberg, C-38, made from the ice that had been the Conger ice shelf. And scientists around the world began to scramble to understand what, exactly, was going on in Antarctica – a part of the world known to be a crucial regulator of global climate, but one still filled with mystery.

“It’s a gut check for the glaciology community” says Peter Neff, a glaciologist with the University of Minnesota. “We have record low sea ice [around East Antarctica]. We have a much stronger heat wave than we ever thought was possible. And an ice shelf collapsing in a place where we didn’t expect it to collapse. … It causes concern for us that we’re not fully appreciating the vulnerability of East Antarctica.”

That vulnerability matters – not only for the ecosystems of this remote, southern continent, but for climate and sea levels worldwide. It is a reminder of how much scientists still don’t know about Antarctica, its ecosystems, and the Southern Ocean that surrounds it. And it shows the importance of the scientific and geopolitical collaboration that takes place on this continent, even as researchers struggle to understand it.

“It’s still an unknown place,” says Catherine Walker, an assistant scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. “For the most part, it’s unexplored. You do your best to understand it with the measurements you can get. But events like this last week – we were all surprised.”

A continent’s complexities

On the one hand, the reason for the Conger ice shelf collapse and the preceding heat wave seems clear. A warming climate has created changes in Earth’s systems, such as rising ocean temperatures and shifts in the way atmospheric currents carry heat and moisture, that in turn lead to events like city-size ice blocks dropping off a continent.

But it’s also far more complicated than that.

(To show just how complicated this is, the weather event scientists say led to the recent Antarctic heat – a band of warm, moisture-filled air called an “atmospheric river” – also brings with it a huge amount of snow. And that snow builds glaciers. Which means it’s not even clear whether a heat wave results in net melting. As Dr. Neff says, “Add tens of gigatons of snow over a couple of days to your glacier, and it can put a wrinkle in your model.”)

Meanwhile, when it comes to polar regions, Antarctica seems – at first glance, at least – to have been less affected by global warming than the north so far.

“If you look at a map of warming over the last 50 years, Antarctica still looks pretty blue, or cold, and the North Pole is red, or warming,” says Dr. Walker. “We hear more about Greenland and shrinking sea ice in the north.”

Indeed, scientists believe that Antarctica serves as a global air conditioner. While ocean waters around the world absorb a quarter of all the carbon humans put into the atmosphere, the Southern Ocean does the most work, absorbing about half of those molecules. And the same churning that makes it so treacherous to sail – or do research – on the Southern Ocean also pushes that heat and carbon into deeper water.

In other words, without the Southern Ocean, the world would be a whole lot hotter, many scientists say. (Again, it’s not quite so simple – the churning also brings up natural carbon from organisms decaying at the ocean floor. But the dominant theory about the Southern Ocean is that it is a carbon sink.)

“We have indications of really important changes,” says Matt Long, an oceanographer with the National Center for Atmospheric Research. “There are direct observations of warming. Of freshening. Of increased freshwater input. We don’t fully understand the implication of those changes for Antarctic marine ecosystems. That’s something crucial for the scientific community to engage in and for the international community to address.”

One impact of all the heat absorbed by the Southern Ocean seems to be that ice is thinning from below. Antarctica holds 90% of the world’s ice, and 70% of Earth’s freshwater volume, according to the National Science Foundation. This means that even partial melting could have a catastrophic impact on coastal communities around the world.

An international collaboration of scientists studying the Florida-size Thwaites Glacier on the western side of Antarctica, for instance, has warned of new cracks and melting in that ice.

Should that glacier fully collapse, it could raise global sea levels by feet – but again, by how much, and how fast, is up for debate.

The recent Conger collapse probably won’t have a big impact on sea levels, scientists say. Still, says Dr. Walker, they are monitoring it.

All nations have a stake

If this isolated continent is the site of mysterious – and perhaps unnerving – changes, it might also be the location of big global answers, both scientific and geopolitical.

Not owned by any one country, Antarctica is governed internationally. The first Antarctic treaty, signed in 1959, demilitarized the continent and explicitly made it a region where countries would collaborate on scientific research. Since then, other agreements have banned mining, oil and gas exploration, and required any fishing industry activity meet conservation goals.

“Internationally, people often look at this treaty system as being very enlightened,” says Claire Christian, executive director of the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition. But there is still a need to monitor activity around the continent to ensure the goals of “peace and science” are being maintained.

Different constituents, she and others say, have conflicting opinions about the best way to do this. For some, economic benefits, such as krill fishing, outweigh conservation efforts, such as setting aside waters as protected areas. To others, scientific exploration is worth disrupting ecosystems.

How Antarctica handles these conflicting goals, in the face of global change, can be illustrative.

And overall, Ms. Christian says, the world needs to care about what happens here – and adjust its climate policies accordingly.

“Antarctica belongs to everyone,” she says. “And everybody in the world has a stake in keeping Antarctica frozen.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.