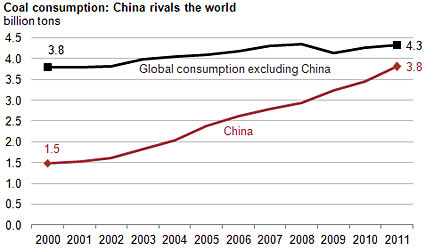

China's coal use rivals rest of world combined - EIA report.

China alone uses almost as much coal as the rest of the world combined, a report from the U.S. Energy Information Administration noted Tuesday, and will likely dominate the coal market in 2013 thanks to the nation’s increasingly ravenous demand for energy.

China alone uses almost as much coal as the rest of the world combined, a report from the U.S. Energy Information Administration noted Tuesday, and will likely dominate the coal market in 2013 thanks to the nation’s increasingly ravenous demand for energy.That bodes well for America’s coal industry, experts say, which has languished in recent years as environmental regulations have tightened and a newfound abundance of natural gas has re-framed the nation’s energy equation, dampening domestic demand for coal.

“Coal use in America is being driven down in large part by EPA regulations, both those that have been announced and those that are forthcoming,” says Heath Knakmuhs, senior director of policy at the U.S. Chamber’s Energy Institute. “Of course we also have plentiful shale natural gas resources that have made natural gas a very attractive alternative from an economic sense to be used to generate electricity.”

But those same regulatory and market forces aren’t necessarily in play in China, Knakmuhs says. Historically, natural gas has been much more expensive in Asia and elsewhere and while the Chinese are exploring ways to exploit their own shale deposits for natural gas and oil, many infrastructure obstacles remain, he says, which makes cheaper coal one of the best energy sources for the power-hungry nation.

(Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, International Energy Statistics)

China’s coal consumption grew more than 9 percent in 2011 and since 2000, the east Asian country has accounted for more than 80 percent of the global increase in coal use, according to the EIA. Although China has vast coal resources within its borders—about 114 billion tons as of 2011 according to the World Coal Association—the country’s coal-mining regions are often far away from demand centers making importing coal from overseas and transporting it by land more cost efficient in some cases.

“There are enhanced opportunities for exports of American coal to China to feed some of that demand,” Knakmuhs says. “While China does have significant internal coal resources they’re often far away from load centers. It does provide an opportunity for American coal suppliers—especially those located in the western U.S. to export enhanced amounts to China.”

But while China’s appetite for more coal might boost Big Coal’s bottom line, there’s no shortage of controversy when it comes to the prospect of transporting higher volumes of U.S. coal to ports on the West coast. Five new export terminals have been proposed in Oregon and Washington, which if built could double the amount of coal the U.S. ships to places like China, India, and South Korea, according to a recent Mother Jones article.

“There’s a lot of coal in the domestic market that can’t be utilized,” Charles Ebinger, energy analyst at Brookings Institution, told Mother Jones. “The Asian market is the fastest-growing coal market in the world. If we wish to continue to export coal [these terminals] are very important…whatever volume of coal we could export would find a market.”

Opponents on the other hand argue that more exports will magnify environmental damage, disperse greater amounts of coal dust in neighborhoods along rail transportation routes, and cause more overall pollution in countries that ultimately burn U.S. coal. Last year, before ascending to his role as chairman of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden (D), who has been lukewarm about coal exports, called for more rigorous environmental reviews of the terminal proposals. The EPA has also raised concerns about the environmental impact of more coal exports, including the effect they would have on greenhouse gas emissions in Asia.

But barring or severely limiting coal exports isn’t likely to do much in the way of mitigating those environmental concerns, some say. Burning coal is still one of the most affordable ways to generate electricity and for rapidly growing countries, scale and cost matter.

“It’s stunning to me that these huge policies ignore simple human realities and all that does is hurt the U.S.,” says Dan Kish, senior vice president of the Institute for Energy Research. “If they don’t get [coal] from the United States they’re going to get it from somewhere whether that’s South America or Indonesia. We don’t hold a corner on any of these resources.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.