China Is Plundering the Planet's Seas

China might be cracking down on luxury spending in watches, cars, banquets and really foul liquor. But the market for pricey fish parts continues relatively unabated. US border officials recently busted a ring smuggling bladders of an endangered fish used for medicinal Chinese soups (here are some images of these prized bladders). The amount of bladders they seized could have sold for more than $3.6 million, said prosecutors. And there are many other smuggling rings out there.

The totoaba, which is native to the Gulf of California, can grow to six feet long and live up to 25 years. Chinese medicine prizes a tubular organ that regulates the totoabas’ buoyancy; the bladder, of sorts, is thought to help promote fertility. According to one report, a similar fish native to Chinese waters called a bahaba, which is also coveted for its bladder, has been known to fetch as much as 3 million RMB ($487,000) per fish – and there’s plenty of evidence of a thriving black market even though it’s nearly extinct and listed by the Chinese government as a “protected species” (links in Chinese).

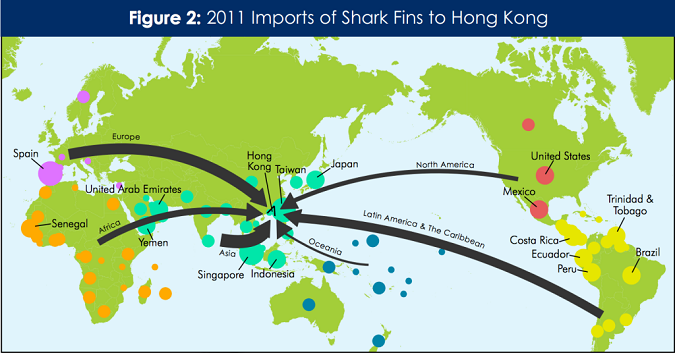

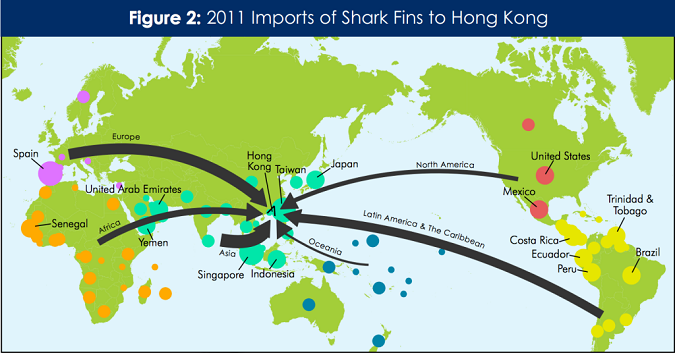

The delicacy that comes from shark fins is far better known than totoaba-bladder soup. And though shark fins are now synonymous with luxury – shark-fin soup can cost around $100 a pop – they too are thought to help stimulate blood flow and cure cancer, among other things. As a result of this trade, nearly 100 million sharks are killed each year, say scientists. That’s 6.4 percent to 7.9 percent of the shark population each year – which means they’re being killed faster than the rate at which they reproduce. Below are all the countries that export shark fins to Hong Kong, which imported some 10.3 million kilograms of shark fins in 2011:

Spain tops the list, followed by Singapore, Taiwan, Indonesia and the United Arab Emirates.Census and Statistics Department of Hong Kong, via Pew Environment Group

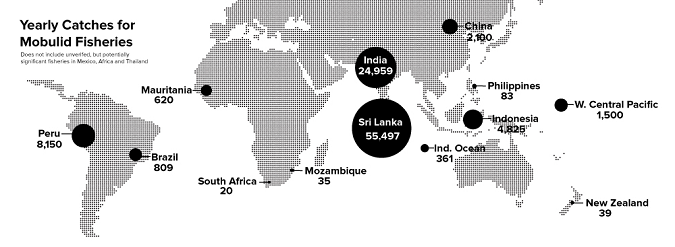

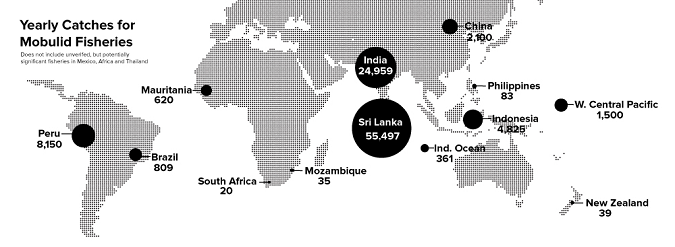

Like totoaba bladder and shark fins, gill rakers of manta rays – cartilage that filters the ray’s food – are prized for their supposed medicinal properties, so much so that they fetch around $251/kg. The $5 million trade in manta ray gill rakers–almost all of which occurs in Guangzhou, in southern China – has depleted manta populations so severely that they were classified as endangered . Here’s where the most rays (including others besides manta rays) are being caught, via Shark Savers:

More than just snuffing out more than 5,000 mantas a year, this trade also threatens diving tourism for local economies. The conservation group Shark Savers puts the value that manta rays generate in terms of the tourism they attract at $140 million a year, which would make each manta ray worth more than $1 million over its lifetime.

That tug-of-war is underway in Mozambique. The black market for manta rays that has encouraged rampant plundering may soon threaten the country’s tourism – one of its main industries – since its mantas are a major diving attraction. One of Mozambique top diving areas, Inhambane, has one of the world’s biggest manta populations. And in the last 10 years, the manta’s numbers there have thinned by 87 percent, say scientists.

“We’re looking at decimation in the next decade or decade-and-a-half. Manta rays are in big trouble along the coastline,” Andrea Marshall, director of the Marine Megafauna Foundation, told the Guardian. “If current trends continue, I don’t give this population more than a few generations.”

It’s the same for sharks, which when viewed as tourism industry assets, can be worth as much as $2 million each, and, in aggregate, generate hundreds of millions of dollars for local economies annually . Shark-diving is now an attraction in more than 40 countries worldwide.

And that’s not just hurting sharks, totoaba and manta rays – China’s black market for fish parts is probably messing up marine ecosystems. Shark finning, for instance, is removing one of the main predators. The unexpected consequences that arise when a species is knocked out of an ecosystem are called trophic cascades.

For instance, as North Atlantic sharks have been killed off, the populations of their prey have grown. And since that prey typically eat coastal bivalves, those have become increasingly scarce. That, among other things, caused a North Carolina scallop fishery to shutter in 2004, and has driven up the cost of clam chowder such that fewer and fewer restaurants in the U.S northeast still serve it. (Note, though, that trophic cascades tend to be incredibly complicated, meaning that the causal relationships are poorly understood. That means that one effect of shark-finning was an oversimplification of the marine ecosystem that “villainized” the cownose ray, resulting in the “Save the Bay, Eat a Ray” campaign – and now that population could eventually be at risk of being overharvested ).

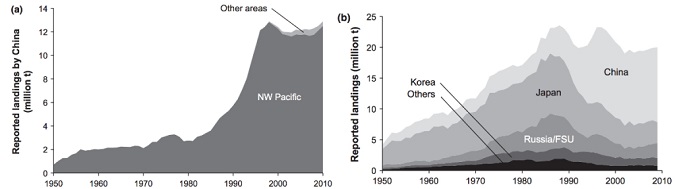

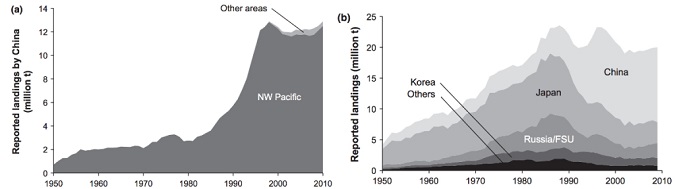

China is dramatically under-reporting what it’s taking from the world’s seas. The average it told the UN Food and Agriculture Organization over the last decade was 368,000 tons each year. A recent European Parliament report puts that number at 4.6 million tons – some 12.5 times more than what China reported. Here’s a look at that, with the waters where it says it’s “landing” fish:

China’s “landing” of fish, with waters it says it’s fishing in on the left, and the accumulated reports of foreign governments on the right.”China’s distant-water fisheries in the 21st century,” Fish and Fisheries, 2012

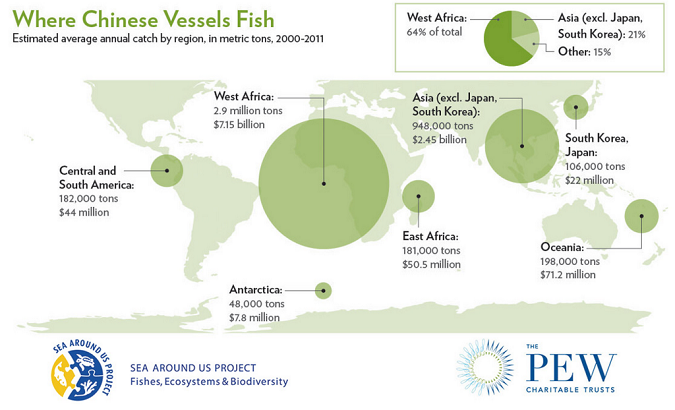

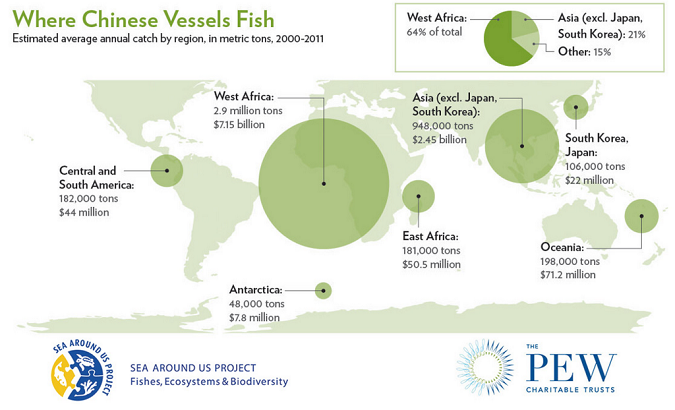

By far the biggest focus of its extraction is Africa, bringing in 3.1 million tonnes a year from African waters – and up to 2.5 million tonnes of that is likely to be illegal. Here’s a look at the geographic breakdown:

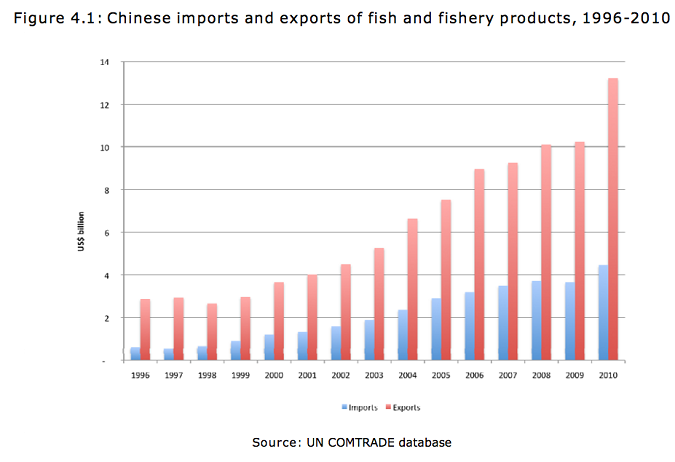

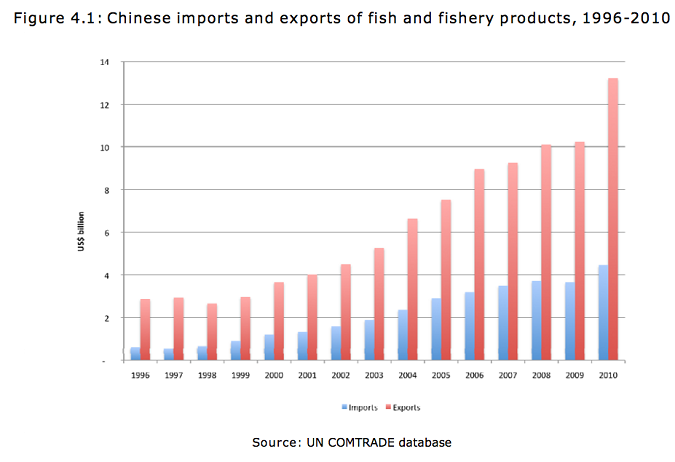

But this aggressive fishing isn’t because Chinese people are suddenly eating a lot more fish. Though China produces 32 percent of the world’s fish products, by weight – the most in the world – it only contributes about 25 percent of global demand. In fact, it’s a net exporter of fish and fishery products:

That amounted to $13.2 billion – about 4.6 million tonnes – in exports in 2010. That number is growing fast, even relative to its imports. Much of that comes from aquaculture, but it’s hard to tell exactly how much. China already over-exploited its own waters years ago, and leading scientists and the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation deem China’s data on domestic catches unreliable due to persistent overstatement. These hazy data invite the question of whether China might be selling at least some of everyone else’s fish back to them. More of a concern, though, is the degree to which that understatement of catches in foreign waters is contributing to over-fishing, which is already becoming an acute problem in many seas around the globe.

Not that any of this would seem likely to change any time soon. As we’ve seen time and again with air pollution and other environmental issues, when China bumps up against the global commons, it usually doesn’t back down without a fight.

The totoaba, which is native to the Gulf of California, can grow to six feet long and live up to 25 years. Chinese medicine prizes a tubular organ that regulates the totoabas’ buoyancy; the bladder, of sorts, is thought to help promote fertility. According to one report, a similar fish native to Chinese waters called a bahaba, which is also coveted for its bladder, has been known to fetch as much as 3 million RMB ($487,000) per fish – and there’s plenty of evidence of a thriving black market even though it’s nearly extinct and listed by the Chinese government as a “protected species” (links in Chinese).

The delicacy that comes from shark fins is far better known than totoaba-bladder soup. And though shark fins are now synonymous with luxury – shark-fin soup can cost around $100 a pop – they too are thought to help stimulate blood flow and cure cancer, among other things. As a result of this trade, nearly 100 million sharks are killed each year, say scientists. That’s 6.4 percent to 7.9 percent of the shark population each year – which means they’re being killed faster than the rate at which they reproduce. Below are all the countries that export shark fins to Hong Kong, which imported some 10.3 million kilograms of shark fins in 2011:

Spain tops the list, followed by Singapore, Taiwan, Indonesia and the United Arab Emirates.Census and Statistics Department of Hong Kong, via Pew Environment Group

Like totoaba bladder and shark fins, gill rakers of manta rays – cartilage that filters the ray’s food – are prized for their supposed medicinal properties, so much so that they fetch around $251/kg. The $5 million trade in manta ray gill rakers–almost all of which occurs in Guangzhou, in southern China – has depleted manta populations so severely that they were classified as endangered . Here’s where the most rays (including others besides manta rays) are being caught, via Shark Savers:

More than just snuffing out more than 5,000 mantas a year, this trade also threatens diving tourism for local economies. The conservation group Shark Savers puts the value that manta rays generate in terms of the tourism they attract at $140 million a year, which would make each manta ray worth more than $1 million over its lifetime.

That tug-of-war is underway in Mozambique. The black market for manta rays that has encouraged rampant plundering may soon threaten the country’s tourism – one of its main industries – since its mantas are a major diving attraction. One of Mozambique top diving areas, Inhambane, has one of the world’s biggest manta populations. And in the last 10 years, the manta’s numbers there have thinned by 87 percent, say scientists.

“We’re looking at decimation in the next decade or decade-and-a-half. Manta rays are in big trouble along the coastline,” Andrea Marshall, director of the Marine Megafauna Foundation, told the Guardian. “If current trends continue, I don’t give this population more than a few generations.”

It’s the same for sharks, which when viewed as tourism industry assets, can be worth as much as $2 million each, and, in aggregate, generate hundreds of millions of dollars for local economies annually . Shark-diving is now an attraction in more than 40 countries worldwide.

And that’s not just hurting sharks, totoaba and manta rays – China’s black market for fish parts is probably messing up marine ecosystems. Shark finning, for instance, is removing one of the main predators. The unexpected consequences that arise when a species is knocked out of an ecosystem are called trophic cascades.

For instance, as North Atlantic sharks have been killed off, the populations of their prey have grown. And since that prey typically eat coastal bivalves, those have become increasingly scarce. That, among other things, caused a North Carolina scallop fishery to shutter in 2004, and has driven up the cost of clam chowder such that fewer and fewer restaurants in the U.S northeast still serve it. (Note, though, that trophic cascades tend to be incredibly complicated, meaning that the causal relationships are poorly understood. That means that one effect of shark-finning was an oversimplification of the marine ecosystem that “villainized” the cownose ray, resulting in the “Save the Bay, Eat a Ray” campaign – and now that population could eventually be at risk of being overharvested ).

China is dramatically under-reporting what it’s taking from the world’s seas. The average it told the UN Food and Agriculture Organization over the last decade was 368,000 tons each year. A recent European Parliament report puts that number at 4.6 million tons – some 12.5 times more than what China reported. Here’s a look at that, with the waters where it says it’s “landing” fish:

China’s “landing” of fish, with waters it says it’s fishing in on the left, and the accumulated reports of foreign governments on the right.”China’s distant-water fisheries in the 21st century,” Fish and Fisheries, 2012

By far the biggest focus of its extraction is Africa, bringing in 3.1 million tonnes a year from African waters – and up to 2.5 million tonnes of that is likely to be illegal. Here’s a look at the geographic breakdown:

But this aggressive fishing isn’t because Chinese people are suddenly eating a lot more fish. Though China produces 32 percent of the world’s fish products, by weight – the most in the world – it only contributes about 25 percent of global demand. In fact, it’s a net exporter of fish and fishery products:

That amounted to $13.2 billion – about 4.6 million tonnes – in exports in 2010. That number is growing fast, even relative to its imports. Much of that comes from aquaculture, but it’s hard to tell exactly how much. China already over-exploited its own waters years ago, and leading scientists and the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation deem China’s data on domestic catches unreliable due to persistent overstatement. These hazy data invite the question of whether China might be selling at least some of everyone else’s fish back to them. More of a concern, though, is the degree to which that understatement of catches in foreign waters is contributing to over-fishing, which is already becoming an acute problem in many seas around the globe.

Not that any of this would seem likely to change any time soon. As we’ve seen time and again with air pollution and other environmental issues, when China bumps up against the global commons, it usually doesn’t back down without a fight.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.