Can the new high seas treaty help limit global warming?

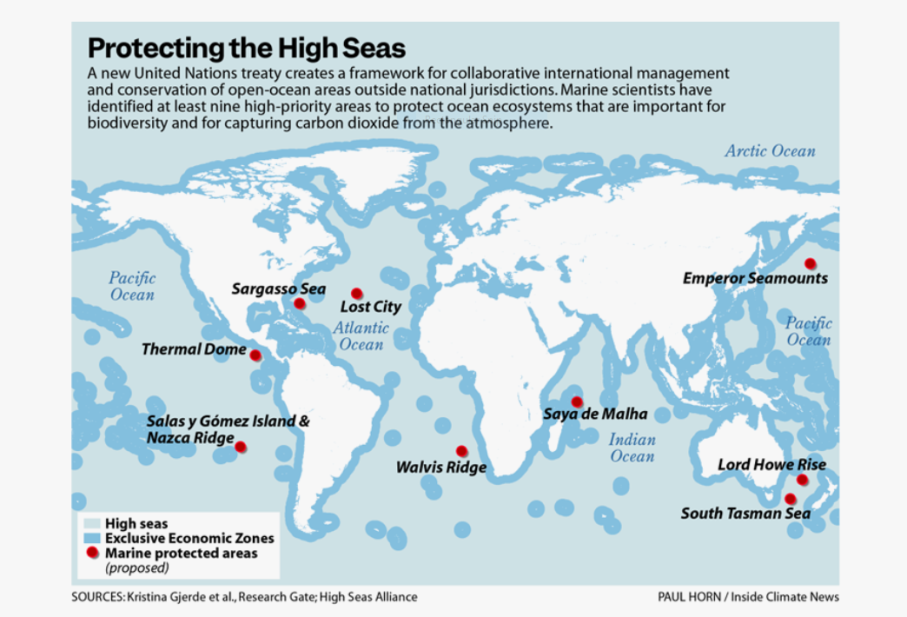

Conservationists and scientists are hopeful that the new high seas treaty, agreed upon in New York on March 4, will end ecological lawlessness by protecting marine biodiversity through future policies that will also protect the planet’s climate. The agreement covers the high seas, the 50 percent of the planet that lies beyond the 200 nautical miles of jurisdiction that nations hold along their coastlines.

Conservationists and scientists are hopeful that the new high seas treaty, agreed upon in New York on March 4, will end ecological lawlessness by protecting marine biodiversity through future policies that will also protect the planet’s climate. The agreement covers the high seas, the 50 percent of the planet that lies beyond the 200 nautical miles of jurisdiction that nations hold along their coastlines.

The treaty is seen as a critical step toward reaching global goals of protecting 30 percent of the planet’s land and oceans by 2030, and an acknowledgment that global climate goals can’t be reached without ensuring healthy ocean ecosystems. Continued degradation of the oceans and loss of biodiversity will speed up global warming. If it remains unchecked, the oceans will die.

Reaching the deal is a sign that countries are “getting the message that we really depend on the planet’s life-sustaining abilities,” said Hans-Otto Pörtner, a climate scientist at the Alfred Wegener Institute and co-chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Working Group II, which deals with climate impacts, adaptation and vulnerability.

Civilization’s rapacious appetite for ocean resources has already disrupted the ability of coastal ecosystems like mangrove forests and seagrass beds to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. That leaves more CO2 in the air, which drives more warming. The global high seas treaty offers a chance to slow down that vicious cycle by protecting parts of the ocean that have not yet been exploited.

“This treaty doesn’t have climate as its focus,” said Lisa Levin, a marine ecologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “There are quite a few delegations that believe that climate should be left to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.”

Those delegations, however, did not stop Levin and others from working to recognize the critical role that marine biodiversity plays in climate mitigation. This language opens the door for the creation of marine protected areas that take the cumulative impacts of climate change and other disturbances into account.

The treaty covers the open oceans, one of the only parts of the Earth’s surface that isn’t divided along national boundaries, similar to Antarctica, although several countries have made territorial claims there. The spirit of the treaty is that the high seas will be managed collaboratively by the whole world, for the common good, for the benefit of ecosystems and for the benefit of the climate.

“We are not disconnected from nature,” Pörtner said. “We are dependent on it and we need to maintain the natural functioning of the planet.”

The Ocean-Climate Connection

The United Nations recognizes the oceans “as the world’s greatest ally against climate change,” central to reducing atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations and stabilizing Earth’s climate. Oceans generate 50 percent of the oxygen in the atmosphere. They capture more than 90 percent of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases and absorb between 25 and 30 percent of human-caused carbon emissions.

Part of the carbon sequestration by oceans is a simple chemical reaction: CO2 molecules dissolve and react with seawater to form carbonic acid, which results in harmful ocean acidification. The second part of the ocean carbon pump is biological. In great pulses of life and decay, marine organisms capture about 33.8 million tons of CO2 daily through photosynthesis and other processes and eventually store much of it long-term in seabed sediments.

The treaty recognizes that role by calling for an integrated approach to ocean conservation that “maintains and restores ecosystem integrity, including the carbon-cycling services that underpin the ocean’s role in climate.”

Pörtner said that, in particular, marine sediments are a huge carbon store that should be left untouched and undisturbed in order to safeguard the climate.

“We must also say that organisms in the ocean play an important role in transporting the carbon from the atmosphere down to the marine sediments,” he added. “So the treaty is an important framework agreement that will help put stocks of those organisms back to natural levels to the extent possible in order to strengthen the natural pathway of carbon export to oceans.”

Fuad Bateh, a special advisor to the State of Palestine, worked to explicitly include the link between ocean biodiversity and climate change in the high seas treaty, advocating the addition of language referencing the threat posed by ocean deoxygenation, alongside warming and ocean acidification.

“The few wins we have,” said the Scripps institution’s Levin, “are thanks to him.”

Levin, who studies ocean deoxygenation, said that the waning abundance of oxygen in the ocean is a direct consequence of warming. This occurs through two mechanisms. The first is that warmer water has less gas solubility and therefore can hold less oxygen. Additionally, as the ocean warms, the surface and deeper layers become more stratified. Deeper waters then have less contact with the surface ocean where they can absorb oxygen from the atmosphere.

Areas High on the List for Future Protection

In a best case scenario for the next 10 years, the new treaty will lead to a global network of marine protected areas on the high seas, said Mary Wisz, a marine scientist at the World Maritime University in Sweden, who also trains early to mid-career diplomats and decision makers, mostly from the global south.

Management of the areas would include rigorous environmental assessments and would try to ensure an equitable distribution of resources from areas covered by the treaty, for example when it comes to genetic resources, or finding beneficial new compounds in marine species.

“The goals of the treaty are that we’re going to protect at least 30 percent of the oceans … in the areas beyond national jurisdiction in an ecosystem-based way,” she said. “And that means that we’re going to have to balance the long term needs for healthy nature with human needs.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.